It may have been difficult for Nike to conceive of any athlete being able to do more for its company than Michael Jordan. In the late 1980s and 1990s, the Chicago Bulls star was omnipresent, helping turn their Air Jordan line of sneakers into a squeaky chorus in school hallways and gyms around the country. Even better, the company had scored big with “Just Do It,” an advertising slogan introduced in 1988 that became part of the public lexicon.

There was just one issue. In spite of Jordan’s growing popularity and their innovative advertising, Nike was still in second place behind Reebok. No other athlete on their roster could seemingly bridge the gap. Not even their new cross-training shoe endorsed by tennis pro John McEnroe was igniting excitement in the way the company had hoped.

In 1989, two major events changed all of that: An advertising copywriter was struck with inspiration, and two-sport athlete Bo Jackson slammed a first-inning home run during the Major League Baseball All-Star Game. The ad man’s idea was to portray Jackson as being able to do just about anything. Jackson went ahead and proved him right.

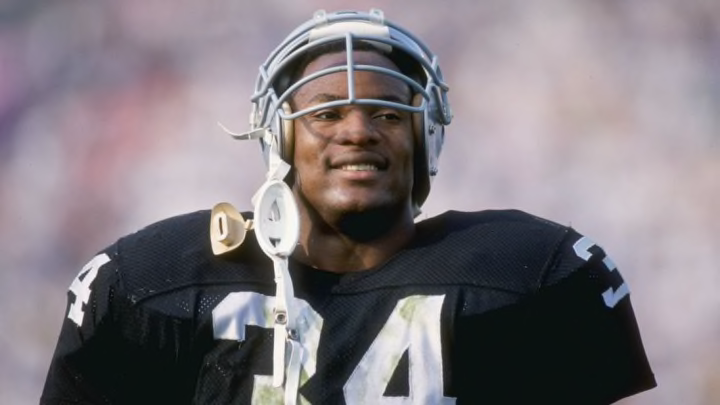

Bo Jackson was an ideal spokesperson for Nike's new line of cross-training sneakers. The Auburn University graduate was making waves as a rare two-sport pro athlete; he was playing baseball for the Kansas City Royals and football for the Los Angeles Raiders. Early commercials featured Jackson sampling other sporting activities like riding a bike. “Now, when’s that Tour de France?” he asked. In another, he dunked a basketball and pondered the potential of “Air Bo.”

At a Portland bar near Nike’s headquarters one evening, Nike vice president of marketing Tom Clarke and Jim Riswold of ad agency Wieden + Kennedy were pondering how best to use Jackson going forward. Clarke wanted to devote the majority of their budget for the cross-trainers to an ad campaign featuring the athlete. The two started lobbing ideas about other people named Bo—Bo Derek, Beau Brummell, Little Bo Peep, and Bo Diddley, among others.

The last one stuck with Riswold. He thought of a phrase—“Bo, you don’t know Diddley”—and went home to sleep on it. When he woke up the next morning, he was able to sketch out an entire commercial premise in minutes. Riswold envisioned a spot in which Jackson would try his hand at other sports, punctuating each with a “Bo Knows” proclamation. Jackson soon realizes the one thing he can’t do is play guitar with Bo Diddley, the legendary musician.

It took longer to shoot the commercial than to conceive of it. The spot was shot over the course of a month, with the crew going to California, Florida, and Kansas to film cameos with other athletes including Jordan, McEnroe, and Wayne Gretzky—all of whom Nike had under personal appearance contracts.

Fearing Jackson might hurt himself trying to skate, the production filmed him from the knees up sliding around in socks at a University of Kansas gymnasium rather than on ice. But not all attempts at caution were successful. When director Joe Pytka grew frustrated that Jackson kept running off-camera and implored him to move in a straight line, Jackson steamrolled both the equipment and Pytka, who had to tend to a bloody nose before continuing.

In portraying any other athlete this way, the campaign may have come off as stretching credulity. But Jackson had already been improving his game in all areas, hitting a 515-foot home run during a spring training win over the Boston Red Sox. In April, he hit .282 and tallied eight home runs. Even when he struck out, he still stood out: Jackson was prone to breaking his bat over his knee in frustration.

After Jackson was voted into the 1989 MLB All-Star Game in July, Nike decided the telecast would be the ideal place to debut their Bo Knows campaign. They handed out Bo Knows pennants for fans and even flew Bo Knows signs overhead. Bo Knows appeared in a full-page spot for USA Today. Even by Nike standards, this was big.

There was, of course, a chance Jackson would be in a bat-breaking mood, which might diminish the commercial’s impact. But in the very first inning, Jackson sent one into the stands off pitcher Rick Reuschel. With a little scrambling, Nike was able to get their ad moved up from the fourth inning, where it was originally scheduled to run. In the broadcast booth, announcer Vin Scully and special guest, former president Ronald Reagan, marveled at Jackson’s prowess. Scully reminded viewers that his pro football career was something Jackson once described as a “hobby.”

Jackson was named the Most Valuable Player of the game. That summer and into the fall, Bo Knows was quickly moving up the ranks of the most pervasive commercial spots in memory, second only to Jordan’s memorable ads for Nike and McDonald’s. Jackson turned up in sequels, trying his hand at everything from surfing to soccer to cricket. Special effects artists created multiple Bo Jacksons, a seemingly supernatural explanation for why he excelled at everything.

It was a myth, but one rooted in reality. After 92 wins with the Royals as a left-fielder in 1989, Jackson reported for the NFL season that fall as a running back for the Raiders. In one three-game stretch, he ran for over 100 yards each. Against the Cincinnati Bengals in November, Jackson ran 92 yards for a touchdown. He finished the season with 950 rushing yards. That winter, he was named to the Pro Bowl, making him the only athlete to appear in two all-star games for two major North American sports in consecutive seasons.

Nike was staggered by the results of Bo Knows, which helped them leap over Reebok to become the top athletic shoe company. They eventually secured 80 percent of the cross-training shoe market, going from $40 million in sales to $400 million, a feat that executives attributed in large part to Jackson. Bo Knows, bolstered by Jackson’s demonstrated versatility, was the perfect marriage of concept and talent. His stature as a spokesperson rose, and he appeared in spots for AT&T and Mountain Dew Sport, earning a reported $2 million a year for endorsements. A viewer survey named him the most persuasive athlete in advertising. If that weren’t enough, Jackson also appeared in the popular Nintendo Entertainment System game Tecmo Bowl and on the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1989.

In 1991, Jackson suffered a serious hip injury during a Raiders game, one that permanently derailed his football career. He played three more seasons of baseball with the Chicago White Sox and California Angels before retiring from sports in 1994.

Jackson's relationship with Nike was dissolved soon after, though the company never totally abandoned the concept of athletes wading into new territory. In 2004, a campaign depicted big names sampling other activities. Tennis great Andre Agassi suited up for the Boston Red Sox; cyclist Lance Armstrong was seen boxing; Serena Williams played beach volleyball. The Bo Knows DNA ran throughout.

Jackson still makes periodic references to the campaign, including in advertisements for his Bo Jackson Signature Foods. (“Bo Knows Meat,” the website proclaims.) In 2019, Jackson also appeared in a Sprint commercial that aimed for surrealism, with Jackson holding a mermaid playing a keytar and having a robot intone that “Bo does know” something about cell phone carriers.

The other key Bo—Diddley—never quite understood why the campaign worked. After seeing the commercial, he reportedly said that he was confused because it had nothing to do with shoes.