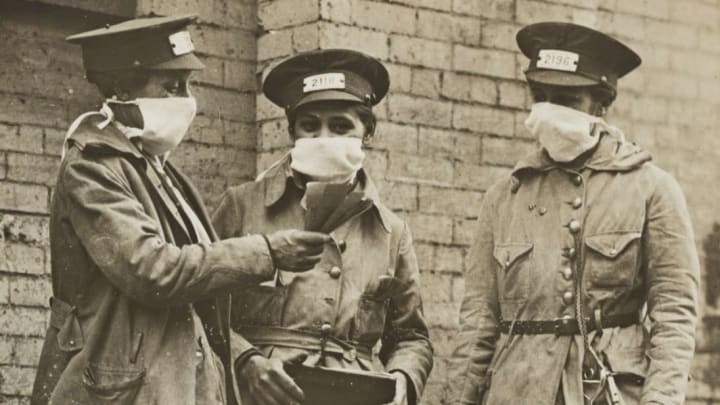

In January 1919, San Francisco residents received some bad news: The second wave of the 1918 influenza was rolling through the city, and masks were mandatory once again.

They already knew the drill. On October 24, 1918, Mayor James Rolph, health officer Dr. William C. Hassler, and other authorities had mandated protective masks to prevent the spread of the disease, and the general public had quickly recognized the practice as a matter of life and death.

“A week ago I laughed at the idea of the mask,“ local Red Cross chairman John A. Britton told the San Francisco Chronicle at the time. “I wanted to be independent. I did not realize that the cost of such independence was the lives of others.”

While most San Franciscans rose to the occasion and volunteers organized mask-sewing events, there were still some staunch dissenters. Law enforcement officers doled out $5 fines for anyone who went mask-less in public, and a couple hundred people who failed to comply were even carted off to jail.

“John Raggi, arrested on Columbus Avenue, said he did not wear a mask because he did not believe in masks or ordinances, or even jail,” an article in the San Francisco Chronicle read. “He now has no occasion to disbelieve in jails. He is in the city prison.”

When Rolph declared that the worst had passed and lifted the mask ordinance in November, people jubilantly tore off their various face coverings and tossed them into the air. By the time Rolph reinstated the rules in January, everyone was used to breathing freely and many were reluctant to return to a masked existence. Thus, the Anti-Mask League was born.

The league was chaired by Emma Harrington, a lawyer who also happened to have become San Francisco’s first female voter in 1911. Two thousand people attended the inaugural meeting, but city officials weren’t intimidated by the size of the opposition.

“We cannot in this matter pay any attention to any public agitators against the mask for the obvious reason that the question is one of public health and not of like or dislike of the mask,” Arthur H. Barendt, president of the San Francisco Board of Health, told the press.

Though the Anti-Mask League continued to meet throughout the month, participants never really landed on a common, actionable goal. According to The Washington Post, some people wanted to organize a petition to repeal the mask mandate, while others were simply demanding that Hassler be fired. Meanwhile, the masks did seem to be helping the city flatten the curve. On January 15, 1919—the day before health officials issued their second decree—there were 510 new flu cases and 50 deaths. On January 26, those numbers had plummeted to 12 and four, respectively.

At the league’s last gathering, having accomplished nothing, members replaced Harrington with a new chairwoman, and the meeting devolved into a state of such chaos that William Scott, who had rented the hall, simply shut off all the lights. The Anti-Mask League never recovered from that ill-fated assembly, but they didn’t need to—on February 1, city officials did away with the mask requirements for the second and final time.

[h/t San Francisco Chronicle]