“When she walked, his heart was ready to burst out of his chest to catch up with her, fall before her, and fly after her in order to find out where she was going and to serve as a bright lantern for her.”

So begins the love affair at the heart of Zabiba and the King, a romance novel about a mighty ruler who falls for a spirited commoner. It was published in Iraq in 2000, and it was written by Saddam Hussein. Yes, that Saddam Hussein.

A “Boring and Incoherent” Bestseller

Though it’s technically unconfirmed that the former Iraqi dictator authored the book, there’s no shortage of circumstantial evidence to suggest that he did—or, at the very least, that he heavily guided a ghostwriter. As Ofra Bengio wrote in a 2002 article for the Middle East Quarterly, Hussein had previously expressed a desire to produce his own literature, and Zabiba and the King (or Zabibah, in the original edition) was published anonymously. According to its introduction, the author wrote it because Hussein had requested works on different aspects of Iraqi existence, and they chose to remain nameless “out of humility, like the sons of Iraq who sacrifice their lives and their valuables and never talk about their great deeds.”

After its release, critics couldn’t seem to muster a single negative word about what Bengio calls a “boring and incoherent” book, and The New York Times reported that the Iraqi media even went so far as to consider it an “innovation in the history of novels.” The rather unmerited abundance of praise—and suspicious lack of opposition—gave rise to rumors that Hussein himself had spun the tale, and it soon became a bestseller. At 1500 dinars, or less than $1, it was also a major bargain. And, if the back cover was to be believed, all proceeds went to "the poor, the orphans, the miserable, the needy, and [to other] charities."

Light on Romance, Heavy on Allegory

Then, there’s the story itself. While Zabiba spends many nights tucked away in the privacy of King ‘Arab’s castle, the amorous pair has nothing on Lady Chatterley and her lover. “Their bodies were so close to each other that they almost touched, and the king kissed her on the forehead” may be the raciest display of affection in the entire novel. In this romantic tale, the couple at the center engages in lengthy conversations about the political atmosphere of the ancient kingdom, pontificating about what it means to be a good ruler and pondering how the nation might honor ‘Arab after he dies. He actually does die at the end, but the story doesn’t continue long enough for readers to find out much about his legacy.

In its entirety, Zabiba and the King functions as a detailed allegory of Iraq during Hussein’s regime. He, of course, is King ‘Arab, and Zabiba represents the Iraqi people. “I am the daughter of my people,” she says in the English translation of the novel. “Though I am fortunate and proud to be loved by the king, the traditions and appearances that the people do not embrace cannot appeal to me.”

Throughout the story, the lovers resist attacks from villains who conspire to overthrow ‘Arab, violate his paramour, or both. The most shocking of these events is the rape of Zabiba by her estranged husband, Hezkel, who is plotting a revolt against ‘Arab. It’s also the least subtle, in allegorical terms: Hezkel is widely believed to symbolize the United States, and his assault is a metaphor for the U.S. invasion of Iraq during the Gulf War. ‘Arab rallies his troops against Hezkel and the other rebels, and both Zabiba and Hezkel perish in the fray. The battle takes place on January 17—the date that the U.S. launched its first missiles in Baghdad in 1991, also known as Operation Desert Storm.

Secret Messages and Stolen Art

While U.S. officials hardly needed a novel to reveal Hussein’s resentment over being run out of Kuwait, they did hope it might shed light on Hussein’s notoriously secretive administration. Members of the CIA meticulously combed through the story looking for insight.

“The book is a kind of dirge,” one official told The New York Times. “The king is talking about his death. Every time I read the book I feel for the king. This is what Saddam wants the people to do—feel for him.”

The CIA’s interest in the novel engendered a fair amount of publicity, which eventually reached the ears of a Canadian artist named Jonathon Earl Bowser. He was shocked to find that the novel’s cover image—a woodsy idyll with a goddess at its center—was an exact replica of his own painting The Awakening. “To state the matter simply,” he wrote on his website, “this printing of Zabibah and the King (with The Awakening on the cover) is a blatant infringement of copyright (but also kind of hilarious).”

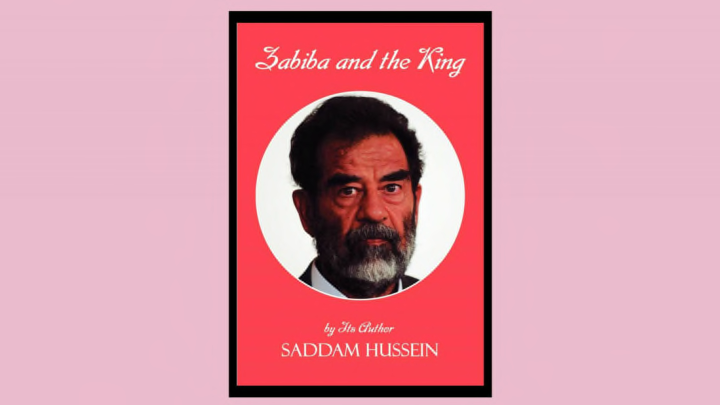

After a London-based fan shipped him a copy, he realized that three of his other paintings were printed inside the book. Unfortunately, Bowser’s lawyers explained that there wasn’t anything he could do unless Hussein published Zabiba and the King in North America, which he never did. (And when an English edition was eventually released in the U.S., the publisher chose a photo of Hussein himself for the cover.)

As for Hussein, he seemed to be satisfied with the success of the book, either as a piece of propaganda or perhaps just as a public diary for his innermost ruminations. He followed it up with three more novels: The Fortified Castle; Men and the City; and Begone, Demons. They’re all very allegorical.