For the first century or so of American independence, people stayed close to home and voted in person at the nearest polling station—much like we do today. As NBC News reports, there were a couple early exceptions to this tradition. In 1775, the town of Hollis, New Hampshire, permitted Continental Army soldiers to send representatives to vote in their stead at a local meeting; and Pennsylvania let soldiers send in their ballots during the War of 1812, though the practice was later declared unconstitutional.

But those scattered instances weren’t enough to make absentee voting a matter of national significance. During the Civil War, however, things changed. If all the Union soldiers stationed away from home couldn’t vote in the presidential election of 1864, it could potentially affect the outcome. Thinking that the majority of those soldiers would support Republican incumbent Abraham Lincoln over Democrat George McClellan, the Republican Party began lobbying for laws allowing far-flung soldiers to cast their ballots from the battlefield.

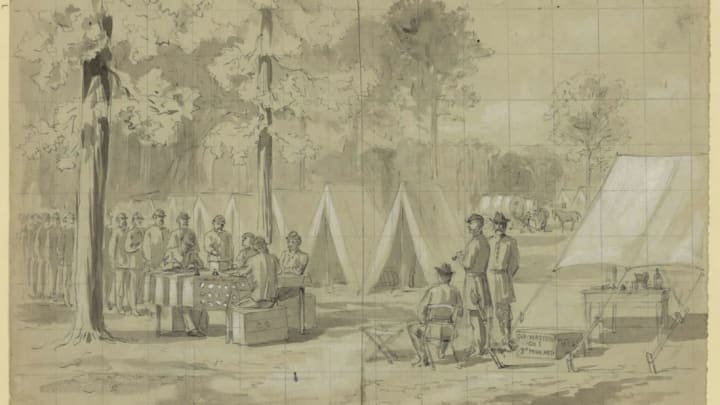

In 1862, Wisconsin became the first state to pass such legislation, which let military leaders turn their camps into makeshift polling locations and mail soldiers’ ballots to state officials. According to the Constitutional Accountability Center, 19 states had followed suit by the general election of 1864. Some mandated that ballots be collected in camps and sent home en masse, while others, like Minnesota, allowed soldiers to mail in their absentee ballots individually.

Meanwhile, Democrats—worried the soldiers’ votes would hurt McClellan’s chances of winning—warned of voter fraud and tried to block efforts to legalize absentee ballots.

“The soldiers are not asking or demanding any such privilege or right,” wrote F.O. Thorpe, a Democratic senator from Wisconsin, “and in our opinion it is simply a scheme of leading partisans in the dominant party … to gain some great advantage to their party in the future.”

While Wisconsin’s mostly Republican legislature was able to quash Thorpe’s dissent, state legislatures with Democratic majorities, like Illinois’s and Indiana’s, didn’t pass laws allowing soldiers to vote in absentia.

Overall, about 150,000 out of 1 million soldiers (in the Union only; the Confederacy held its own election) were able to vote by mail. Since Lincoln won the popular vote by more than 408,000 votes—and the electoral vote with 212 over McClellan’s paltry 21—it’s unlikely those absentee ballots actually swung the election in his favor, but they did set the precedent for expanded absentee voting laws for wars (and pandemics) in years to come.

[h/t NBC News]