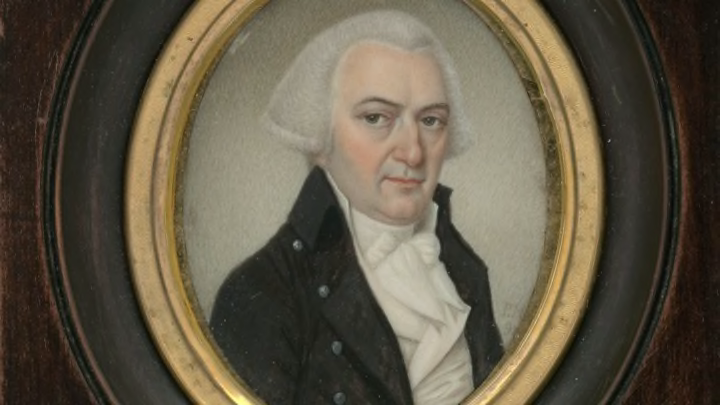

On the attendance list of 1787’s Constitutional Convention are some of the most recognizable names in American history, including George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison. There are also several dozen who hardly ever get mentioned—like Pennsylvania delegate Gouverneur Morris.

Born to wealthy New Yorkers on January 31, 1752, Morris attended King’s College (Columbia University) and secured a seat in New York’s congress in 1775. Just three years later, he represented New York at the Continental Congress, signed the Articles of Confederation, and soon took a financial position in the new government.

Political savvy wasn’t Morris’s only distinguishing characteristic. Witty and dashing, Morris was something of a philanderer; he also had a wooden leg, the result of a carriage accident in 1780. John Jay cheekily alluded to his friend’s preoccupation with women in a letter written after the crash. “Gouverneur’s Leg has been a Tax on my Heart,” he said [PDF]. “I am almost tempted to wish he had lost something else.”

Morris’s charisma made him a standout at the Constitutional Convention several years later. According to the National Constitution Center, he spoke 173 times throughout the affair—more often than any other delegate—and argued passionately for a solid national government. He also abhorred slavery, which he considered “in defiance of the most sacred laws of humanity.” His writing skills were even stronger than his convictions. Morris tweaked the linguistic minutiae of the Constitution so much that he’s sometimes called the “Penman of the Constitution.” After the Convention, Morris served as a minister to France, became a New York senator, co-founded the New-York Historical Society, and chaired the Erie Canal Commission.

But by 1816, Morris’s health had begun to fail. Gout was wreaking havoc on his organs, and the 64-year-old statesman spent the fall bedridden at his family home in Morrisania, New York, experimenting with remedies—everything from enemas and bloodletting to laudanum and herbal infusions. As Andrew Martin writes for Medium, the most pressing issue was a urinary blockage, which may have been a urinary tract infection. Increasingly panicked over his inability to urinate, Morris tried to clear the occlusion by inserting a sliver of whale bone (possibly borrowed from a corset of his wife’s) into his urethra.

According to fellow New York politician Rufus King, this wasn’t the first time Morris had fashioned a makeshift catheter for himself. “Some years ago … he performed the same operation with a flexible piece of hickory; the success on this occasion probably emboldened him to repeat the experiment,” he wrote in a letter.

Unfortunately, the second trial proved less successful—fatal, in fact. Morris’s inner tissue was torn and inflamed, and he developed a penile infection that resulted in his death on November 6, 1816.

The details of Morris’s ill-advised surgery attempt didn’t appear to make the papers; the Maryland Gazette called it only “a short but distressing illness.” Morris didn’t seem to fixate on his particular cause of death, either. “Sixty-four years ago, it pleased the Almighty to call me into existence—here, on this spot, in this very room,” he said toward the end. “And now shall I complain that he is pleased to call me hence?”

[h/t Andrew Martin via Medium]