Food has been used as an artistic medium since ancient times, but its sweetest period may have been the Renaissance, when sugar sculptures graced the many banquet halls and tables of Europe’s most elite.

Sugar, Refined

Confectioners cast, pressed, pulled, and spun sucrose into the elaborate forms of Greek palaces, English Gothic cathedrals, and mythical figures like Venus and Hercules as edible adornments for the wealthy. According to London-based food historian (and founder of AVM Curiosities) Tasha Marks, the confectioners creating these sculptures were treated in the same vein as more traditional artists. In fact, Italian sculptors such as Jacopo Sansovino and Danese Cattaneo even dabbled in edible sugar creations.

“Sugar was an expensive commodity right up until the 19th century,” Marks tells Mental Floss. “It was a luxury that eventually [crossed] class boundaries. However, for centuries, it was something only the very wealthy could afford.”

Although Western Europeans first discovered the allure of sugar during the Crusades, they initially used it as a spice, preservative, or for medicinal purposes like curing stomach ailments and treating wounds. It wasn't until the method of refining raw sugar from sugarcane plants became itself more refined that sucrose was so sought-after. “The growth in the consumption of sugar went hand-in-hand with the evolution of the dessert banquet,” Marks says. “When sugar transformed from a spice and sweetener into a status ingredient, the consumption of it grew exponentially.”

At the same time, European explorers were making their way to the Americas, bringing with them sugar cane to plant, as well as enslaved people from Africa to tend the fields. "As tables groaned with the weight of sugarcoated luxuries, in the cane fields of the Caribbean and in the bows of ships there was a very different narrative unfolding," Marks wrote in a recent article for Art UK about the link between the transatlantic slave trade and the growing popularity of these sugary displays.

Sugar-high art

Confectioners worked meticulously, creating extravagant displays of sugary delight that Marks says often crossed the boundaries of table dressings into installation art and even theater. While some of these edible wonders stayed intact for longer periods, others, according to the Getty Museum (which highlighted Renaissance-era sugar sculptures in its 2015 exhibit, The Edible Monument: The Art of Food for Festivals), “were handed out to honored guests, who devoured them after returning home.” Sometimes, even the general public was allowed to partake in the festivities.

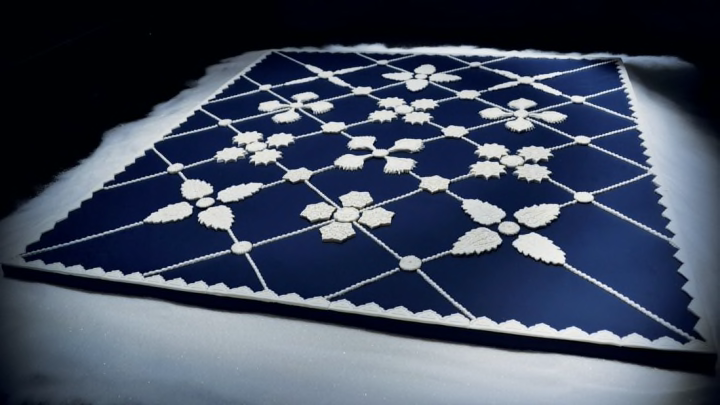

The more exclusive the event, the more elaborate and excessive the sculptures. Some were gilded with gold leaf; others were painted in various colors to make figurines and structures more life-like (and conceal the sugar’s brownish or red hue). There was also the use of pastillage, a quick-drying paste made from powdered sugar and gum arabic, which helped catapult sugar into a whole new artistic realm. With the advent of this edible substance, confectioners could cast sugar into extremely hardened shapes, after working and molding it like clay.

When confectioners finished creating the various pieces (including those that had been pulled, blown, and pressed) or a sculpture, they then welded them all together with a gas torch. This resulted in table centerpieces, displays, and adornments that were often just part of a much larger sugary feast, one brimming with dishes like sugar-coated roast quail and pigeon, glazed fruits hanging from trees, and blancmange, a sweet and milky panna cotta-style dessert in which sucrose plays a starring role.

Some of the best documented examples of sugar sculptures were the ones created for Henry III of France during his visit to Venice in 1574, a banquet that Ewa Kociszewska, a faculty member at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, recently wrote about for Renaissance Quarterly [PDF]. Kociszewska notes that unlike most sugar sculptures of the time, the ones at Venice’s Palazzo Ducale, where the banquet took place, were made of a sugar that was stark white, “reminiscent of sculpture in marble.”

A Sugar Sculpture Renaissance

Centuries later, such Renaissance-era sugar sculptures continue to inspire the works of artists worldwide. This includes European food historian Ivan Day, whose recreation of Menon’s 18th century, 9-foot-tall sugar sculpture depicting the classical Palace of Circe (home to the sorceress from Homer’s Odyssey) was part of the Getty Museum’s 2015 exhibit; and cake designer Margaret Braun, who crafted 2000 hand-hewn cups entirely of sugar for New York’s Museum of Arts and Design that same year.

Marks's own sucrose sculptures include Alabaster Ruins, a 2017 piece that drew inspiration from Elizabethan-era structures through the use of both ancient and modern sugar-sculpting techniques, such as a 17th century recipe for sugar paste and 3D printing technology.

“[I believe] sugar sculpture is an artistic medium of tremendous flexibility,” Marks says. “It’s uniquely placed to lure us in, then both impress and unsettle us in equal measure.”