She may be more than 55 years old, but Harriet the Spy has aged pretty well. Though a modern-day Harriet M. Welsch would no doubt make use of cell phones, internet research, and GPS tracking to complete her missions, author Louise Fitzhugh captured the not-always-nice inner thoughts and feelings of a kid on the brink of adolescence so well that her novel, first published in 1964, transcends the decades. Here are a few facts about Harriet the Spy hat we scribbled in our notebook. (DO NOT share with anyone.)

1. Author Louise Fitzhugh was surprised that Harriet the Spy was popular.

She referred to Harriet as “a nasty little girl who keeps a notebook on all of her friends.” But kids apparently identified with that “nasty” child: the book has since sold more than 5 million copies.

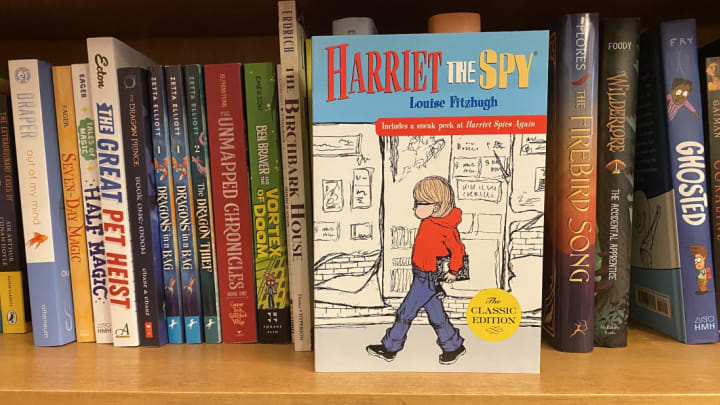

2. Louise Fitzhugh also illustrated Harriet the Spy.

In fact, she "always considered herself a painter first," biographer Leslie Brody told the LA Review of Books, adding that "Regarding her book illustrations, Louise was a perfectionist. She worked with a magnifying glass at hand."

Fitzhugh turned to children's lit when she couldn't make enough money as a painter. Her first big success was illustrating her friend Sandra Scoppettone's book Suzuki Beane, about a girl who lived on Bleeker Street in Manhattan's Greenwich Village neighborhood. That got her foot in the door at Harper Books, where she was able to sell Harriet the Spy on a mere four-page summary.

3. Ole Golly was likely inspired by Louise Fitzhugh’s own nannies.

Although she drew inspiration for Harriet’s big city espionage from her adult life in New York, Fitzhugh came from well-to-do Southern socialites. She grew up in a mansion in Memphis during the Great Depression and had many nannies and household staff of her own.

4. Louise Fitzhugh gave some of her close friends a nod in Harriet the Spy.

When she spies on Harrison Withers and his 26 cats through his skylight, Harriet is careful to note the name of each and every cat. They include the names of favorite authors Dostoevsky and Faulkner, but also folks from her inner circle, including Alex (Alixe Gordin, Fitzhugh's partner for a decade), Sandra (Fitzhugh's Suzuki Beane co-creator), and Marijane (writer Marijane Meaker), among others.

5. Louise Fitzhugh refused to do any publicity for Harriet the Spy.

She didn't enjoy being in the public eye, and thus declined to do readings or make any appearances to help promote the book. Jennifer Wilson writes at The New Republic that "a bohemian, countercultural disgust with the book marketing game" and "the political climate at the time" were also part of her reluctance. Fitzhugh was a lesbian and, as Brody writes in her biography of the writer, Sometimes You Have to Lie, "exposure could have caused real trouble—not just for herself, but also for her agent, editor, and publisher, all of whom might be publicly hounded, censored, and boycotted and suffer humiliating personal attacks.”

6. Harriet the Spy was banned.

Although it seems fairly innocuous now, at the time it was released, some parents felt that Harriet set a bad example: Not only did she spy on people, but she was disrespectful, talked back, lied, and cursed. Another reason frequently cited was that Harriet was too abrasive and behaved improperly for a girl.

7. In the 1960s and '70s, young girls formed Harriet the Spy clubs.

OK, so the critics weren’t totally wrong about the book encouraging kids to spy on their parents. (To be clear, they were still wrong to ban it. And also, what kid doesn’t spy on their parents?) To emulate Harriet, fans formed Harriet the Spy clubs where they dressed like Harriet and took notes on their parents’ activities and conversations.

8. Louise Fitzhugh penned two Harriet the Spy sequels.

The Long Secret (1965) was published just a year after Harriet the Spy but didn’t find the same audience or rave reviews from the critics. The sequel finds Harriet spending her summer vacation spying on the residents of Water Mill, Long Island, to find out who has been leaving anonymous notes all over town. The second, Sport, was written by Fitzhugh but published in1979, five years after her death from a brain aneurysm. The novel follows Harriet’s pal Sport as he navigates how to handle an inheritance—and all the problems that come with it. Sport took her a long time to finish, in part because she was tired of writing about Harriet’s world and was ready to move on.

9. There were also some Harriet the Spy sequels not written by Louise Fitzhugh.

Harriet Spies Again (2002) and Harriet the Spy, DoubleAgent (2005) were approved by the Fitzhugh estate, but although Fitzhugh is credited as the co-author for both, she was not involved with either of them.

10. Harriet the Spy resonates with those who identify as LGBTQ.

Fitzhugh herself was gay, but Harriet’s sexuality is never mentioned. However, the fact that she felt more comfortable in clothes thought of as “boy” clothes at the time—a sweatshirt, jeans, her spy tool belt—and was unapologetic about it spoke to kids who felt didn't but couldn't put their finger on why, according to Kathleen Horning, the director of the Cooperative Children's Book Center at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. "I have talked to so many adult lesbians who felt the same way about Harriet," Horning told NPR. "Particularly if you were growing up in the '60s when you really didn't have any other people like you, Harriet was it. What the book told us is that we could be ourselves and survive."

11. There’s an animated Harriet the Spy series on the way from Apple TV+.

Beanie Feldstein is slated to voice Harriet, while Jane Lynch will be filling Ole Golly’s sensible shoes. Harriet’s nemesis, Marion Hawthorne, will be played by Lacey Chabert. Although other attempts at adapting the book to a movie or series have brought Harriet and her pals into a more modern-day setting (including Harriet the Spy: Blog Wars), this adaption by Apple and produced by The Jim Henson Company will stick to 1960s New York.