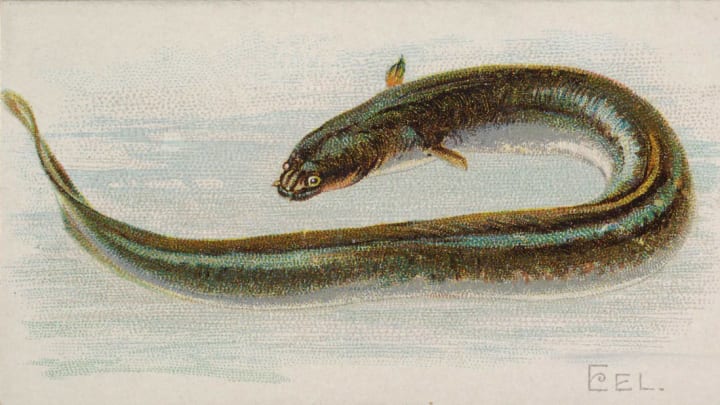

Eels are a diverse group of fish that tend to look pretty slender; you might even call them “eel-longated.” Some are big, some are small, and more than a few come with nightmarish jaws. Naturalists have been probing their mysterious habits for millennia, and here are 11 things we’ve learned about the creatures.

1. Electric eels technically aren’t eels.

If you’ve caught a long, skinny fish, that might be an eel—but it could also be something else. True eels are members of the order Anguilliformes, which includes 800-plus species. The so-called “electric eels” of South America don’t count because they belong to the unrelated order Gymnotiformes. Genetically speaking, electric eels have closer ties to catfish and carp. Shocking, right?

2. Moray eels have secret jaws.

A large family of Anguilliformes, moray eels don’t produce much suction when they bite things. So to drag prey down their gullets, the fish use a secondary set of “pharyngeal jaws” hidden deep inside their throats. Lined with wicked teeth, the jaws can shoot forward and grab struggling victims that are already trapped between the other set of jaws.

3. The American Eel’s lifecycle is complicated.

Here’s the CliffsNotes version: American eels (Anguilla rostrata) hatch from eggs laid in the Atlantic Ocean. The Sargasso Sea—a body of mid-ocean water whose borders are defined by various currents—is thought to be a major spawning ground for the species (although other breeding sites might also exist). At first, baby eels are leaf-shaped larvae; later, they become 2- to 3-inch-long juveniles called glass eels; find new homes in brackish coastal habitats in yet another stage known as elvers; then, in the final stage before sexual maturity, they become yellow eels. Anywhere from three to 40 years later, they become silver eels measuring up to 5 feet long and return to the Atlantic to breed.

4. European glass eels might use magnetic fields to navigate.

Yet another migratory fish, this species (Anguilla anguilla) follows the same basic life cycle as the American eel. It both spawns and dies in the North Atlantic, spending the remainder of its life in coastal Europe. Some evidence suggests that juveniles (i.e. “glass” eels) can potentially sense magnetic fields and adjust their swimming habits accordingly. If true, this might help explain how they find their way to the Sargasso and back.

5. Some oceangoing snakes target moray eels.

Besides their rope-like physiques, eels and snakes don’t have much in common. However, there are over 50 snake species that spend all or some of their lives in the ocean, and certain amphibious types known as sea kraits regularly hunt moray eels, eating them whole. One researcher even described a 5-foot-long sea krait swallowing a 4-foot-long moray.

6. Eel meat is huge in Japan.

Unagi don is a popular summertime entrée in the Land of the Rising Sun. Its main ingredient is roasted eel meat—usually taken from a Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica) or the American species—that is served with pepper and sauce over a bed of rice. Questions have been raised about the sustainability of harvesting American or Japanese eels, however, seeing as both species are classified as endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

7. Be warned: Conger eels bite the occasional diver.

Just ask Jimmy Griffin, a veteran diver who was suddenly attacked by one of the sharp-toothed eels near County Galway, Ireland, in 2013. Conger eels can weigh over 200 pounds; the eel in this particular story measured around 6.5 feet long. It approached Griffin 82 feet below the ocean’s surface and took a bite out of his face, inflicting a wound that required 20 stitches and plastic surgery. Unfortunately for diving enthusiasts and fishermen, this wasn’t an isolated case.

8. A new eel described in 2011 looked weird enough to get its own, distinct family.

Protanguilla palau lives in reef caves near the Republic of Palau and has unique gill structures for a modern eel. Since the animal didn’t look like it comfortably belonged with any known eel families (like the morays), scientists established a brand-new one just for it: Protanguillidae. Experts think the ancestors of Protanguilla palau diverged from other early eels around 200 million years ago and took a separate evolutionary path.

9. Waterfalls aren’t an obstacle for the New Zealand longfin eel.

Noted for their climbing ability, juvenile longfins can scale 65-foot waterfalls, as well as manmade dams. The migratory species frequents New Zealand’s freshwater lakes and rivers.

10. One moray eel can feed in the open air.

“Snowflake moray eel” is a cute-sounding name, but they’re fearsome predators. Research published in 2021 shows they’re capable of (partially) hauling themselves onto dry land and grabbing prey like crabs above the waterline, courtesy of those pharyngeal jaws.

11. True eels are considered “ray-finned fishes.”

So are half of all the vertebrate animals alive right now. Ray-finned fishes—a group which includes the Anguilliformes—are named after the stiff, jointed bones that underlie their fins. This stands in contrast to the fleshy, muscular extremities of “lobe-finned fishes” like coelacanths.