Thomas Jefferson accomplished a great many highly important things in his career as a Founding Father, statesman, diplomat, and politician—but he might have missed his calling as a furniture designer. Our nation’s third president basically invented the swivel chair, as well as a walking stick that folded into a small chair, a revolving bookstand that allowed bibliophiles to read five books on a whim, and a portable lap desk on which he drafted a little document called the Declaration of Independence.

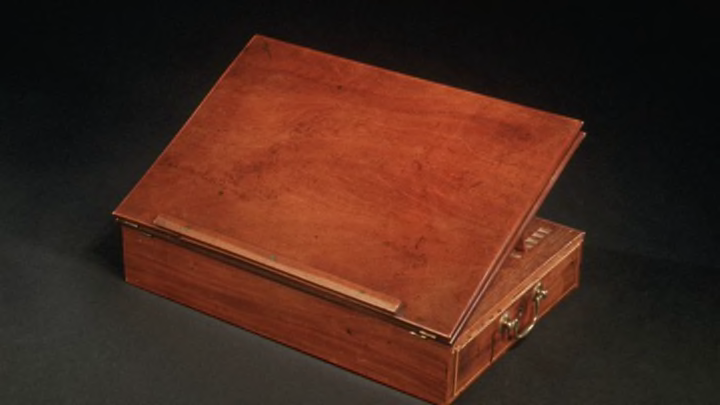

As the delegate from Virginia to the Continental Congress in 1776, Jefferson had the “writing box,” as he called it, built by a Philadelphia cabinetmaker named Benjamin Randolph. It’s made of mahogany and is about 10 inches long by 14 inches wide by 3 inches deep, but it does a lot with the limited space. The desk includes a folding board attached to the top to increase the writing surface, as well as a lockable drawer with space for paper, pens and a glass inkwell.

Jefferson used it for almost 50 years, ultimately giving it to his grandson-in-law, Joseph Coolidge Jr. When Jefferson’s granddaughter Ellen Randolph married in 1825, Jefferson wanted to give his new in-law a handmade, inlaid desk. Unfortunately, the ship carrying the desk from Richmond to Boston sank, so Jefferson passed down the trustworthy writing desk instead.

On November 14, 1825, just over seven months before he died, Jefferson wrote to Ellen:

Now I happen still to possess the writing-box on which it [the Declaration] was written. It was made from a drawing of my own, by Ben. Randall, a cabinet maker in whose house I took my first lodgings on my arrival in Philadelphia in May 1776. And I have used it ever since. It claims no merit of particular beauty. It is plain, neat, convenient, and, taking no more room on the writing table than a moderate 4to. volume, it yet displays it self sufficiently for any writing. Mr. Coolidge must do me the favor of accepting this. Its imaginary value will increase with the years, and if he lives to my age, or another half century, he may see it carried in the procession of our nation's birthday, as the relics of teh saints are in those of the church.”

If not apparent already, the note that Jefferson attached under the writing board solidifies a sense that the man knew his place in history: "Politics as well as Religion has its superstitions. These, gaining strength with time, may, one day, give imaginary value to this relic, for its great association with the birth of the Great Charter of our Independence."

In a February 27, 1826 letter thanking his grandfather-in-law for the gift, Coolidge wrote, “—I would fain consider it as no longer inanimate, and mute, but as something to be interrogated and caressed."

The desk stayed in the Coolidge family for the next half a century until April 1880, when the family donated it to the government. It was first displayed in the Department of State and then transferred to the Smithsonian in 1921, where it remains to this day.