Like his creation, spork inventor Samuel W. Francis was many things at once: he was a doctor, a society man, a novelist, a philanthropist who appreciated birds of prey, and a prolific idea man. In fact, the history of the man who first dreamed of a pronged spoon may be weirder than the utensil itself.

Fork-spoon combinations have been around for centuries, largely in the form of two utensils fused together at the handle, so one end features fork-like spears and the other the rounded surface of a spoon. (They’re handy for eating desserts like candied fruit.)

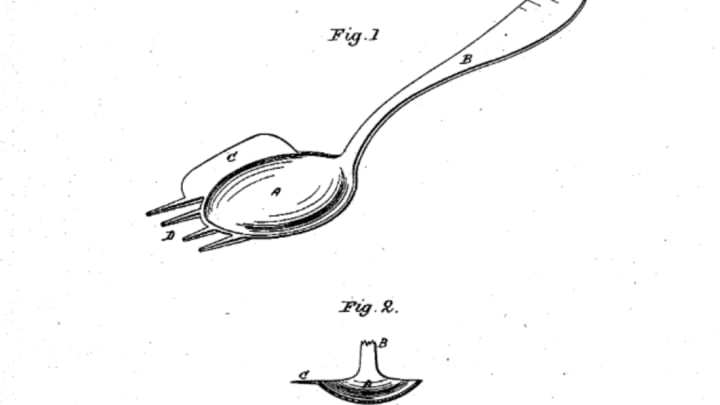

However, one of the earliest design ancestors of the modern spork was patented by Francis, a respected physician, in 1874. His patent for combined knives, forks, and spoons shows a Frankenstein’s monster of a utensil: a mash-up of a spoon with prongs on the end and a straight section protruding from the side. Plastic hadn’t yet taken off as a material, so it was designed to be metal.

The spork was actually one of Francis’ saner ideas. He was constantly trying to improve the human condition, in increasingly outlandish ways. He tried inventing new kinds of sleds, calling cards, and sewing machines. He patented a typewriter that looked like a piano, nicknamed the “literary piano.” In 1868, he invented a self-opening coffin, “an effectual method of rescuing a person, if buried alive.” It featured spring-loaded catches so that if the person were to wake up from a trance and push on the top of the casket, it would pop open. He owned 12 patents by the time he died, including his combination utensil.

A typewriter patented by Samuel Ward Francis in 1857. Image Credit: The National Museum of American History

Despite his prescience, Francis didn’t make much headway with his inventions in his lifetime. The plastic pronged spoon familiar to all cafeteria dwellers came around almost a century later. The word spork can be traced back to a dictionary entry from 1909, but a U.S. company didn’t trademark the name Spork until 1970. The plastic spork quickly became a staple utensil for schools, prisons, and fast food chains. “The spork made business sense: two plastic utensils for the price of one,” writes Bee Wilson in her 2012 book Consider the Fork: A History of How We Cook and Eat.

But Francis wasn’t much of a businessman. Born the son of an upper-class New York doctor and educated at Columbia and NYU, he didn’t need to be. “He moved in the highest society,” The New York Times noted in his obituary. And he dedicated himself to charity and the common good. In 1864, he donated a snowy owl to Central Park. After moving from New York City to Newport, Rhode Island in 1863, he helped start the Sanitary Protection Agency, which later became the city’s Board of Health. He also founded the Newport Natural History Society and the Newport Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

When he wasn’t tending to people with skin diseases or starting animal-protection societies, Francis dabbled in the literary life. He wrote a novel called Life and Death, published in 1871, as well as stories and works of nonfiction, such as an 1861 book about hydrotherapy. His essay “Man and Nature” features a long treatise on how various animals, fruits, vegetables, and nuts resemble human body parts. (Of note: his comparisons between the fig and the male scrotum; his assertion that the uterus and fallopian tubes, when dissected, look like a crab.)

Upon his death in March 1886, coverage of his funeral in The New York Times declared that “Rarely is so large an assembly of representative men seen at the funeral of a Newport citizen, and rarely is so general a tribute of esteem and affection paid the memory of a departed friend as was accorded to Dr. Francis.” It’s a wonder he couldn’t convince more of those friends to use his ingenious new utensil.

[h/t: Vox]