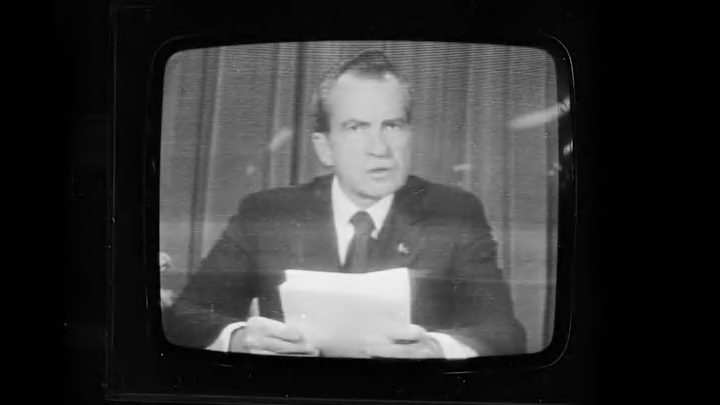

The Watergate scandal remains one of the most highly publicized and contentious episodes in American history. What started as an attempt to secretly record the goings-on at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington, D.C., turned into a full-fledged political nightmare that took down dozens of politicians, forever marred Richard Nixon’s presidency, and changed the American public's opinion of their government. In honor of this year being the 50th anniversary of Nixon’s resignation, here are 10 tricky facts you need to know about the Watergate scandal.

- Tape on the doors led to the burglars' arrest.

- Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein didn't write the first story about the Watergate break-in.

- Nixon's own paranoia created the evidence that sunk him.

- Bob Woodward met Mark Felt—the future "Deep Throat"—by chance years earlier.

- We don't know what the burglars were breaking in for.

- Americans weren't in favor of Nixon's removal at first.

- The government's chief prosecutor didn't think Nixon knew about the Watergate break-in.

- The origins of the "Watergate Salad" are still a mystery.

- The National Archives tried to salvage the 18.5-minute gap from Nixon's recordings.

- More than 200 scandals have -gate attached to them.

Tape on the doors led to the burglars' arrest.

The Watergate scandal kicked off on June 17, 1972, when five burglars—Virgilio Gonzalez, Bernard Barker, James McCord, Eugenio Martínez, and Frank Sturgis—were arrested during a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters located inside Washington, D.C.'s Watergate complex. It was soon established that the group had ties to the Committee to Re-Elect the President and to the White House itself.

The whole break-in came undone when a Watergate security guard noticed that tape had been placed on the latches of doors in the basement of the building and in the stairwell leading to the DNC headquarters. The tape was left by James McCord, who previously worked for the CIA and FBI. Thinking it was put there by workers, security guard Frank Wills removed it. But when he came around again, the tape had reappeared, which was enough for Wills to call the cops and alert them that a burglary might be in progress.

Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein didn't write the first story about the Watergate break-in.

Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein will forever be known for their investigative work during the Watergate scandal, but they weren't the first at the paper to cover the break-in. In the June 18, 1972, edition of the paper, a longtime police reporter named Alfred E. Lewis got the first byline concerning the story. In the Post's 1994 obituary for Lewis, reporter Martin Weil expanded on Lewis's contributions, saying, "a familiar and trusted figure to top police officials, [Lewis] went into the building with investigators and remained there unchallenged through the day, gathering information available to no other news outlet."

The details that Lewis obtained helped convince the paper's editors that the crime went far beyond a simple robbery, with Woodward saying that Lewis's work "laid the foundation for what the paper was able to do in reporting the story."

Nixon's own paranoia created the evidence that sunk him.

It's possible that President Nixon wouldn't have faced any consequences for his involvement in the break-in and coverup, the investigation of which eventually revealed “a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage conducted on behalf of President Nixon’s re-election and directed by officials of the White House,” the Post reported.

There were a lot of others to take the fall, and there was a lack of evidence directly linking the president to the illegal activity. It's easy to imagine him plausibly denying everything, condemning the perpetrators as misguided supporters, and moving on. Except he taped himself confessing. A lot. Though by no means the first to record White House meetings, Nixon was extremely paranoid while in office, believing that, as he was spying on allies and rivals, they must be doing the same to him. In that paranoia, he bugged his own office at the White House, a profound misstep that would ultimately create the "Smoking Gun" tape, where Nixon is heard talking with Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman about asking the deputy director of the CIA to interfere with the FBI's investigation of the break-ins.

Bob Woodward met Mark Felt—the future "Deep Throat"—by chance years earlier.

When Woodward was still a Navy lieutenant in his twenties, he was sent to deliver a package to the White House. As he sat in the waiting room for someone to sign for it, he met Mark Felt, an assistant director for the FBI. The two struck up a conversation and Woodward asked Felt for his number to keep in touch. Woodward recalled that he would call Felt occasionally for career advice, seeing him as something of a mentor.

Eventually, Felt began feeding Woodward inside information, starting with details about the assassination attempt on Alabama governor George Wallace. Once the Watergate arrests happened a month later, Felt, who was never a fan of Nixon, became a natural source for Woodward.

We don't know what the burglars were breaking in for.

Were they trying to find evidence of a connection between Cuba and Democratic Party fundraising? Were they targeting DNC chair Larry O'Brien for financial secrets? Or political strategy insights? Or to get dirt linking prominent Dems to prostitution? We don't really know, and we probably never will. These are the major competing theories, some asserted by burglar James McCord, but there's zero conclusive information on what the robbers were even looking for.

Americans weren't in favor of Nixon's removal at first.

Only about a quarter of Americans were in favor of Nixon's removal from office by the middle of 1973, even as stories about secret Oval Office recordings and cover-ups began making headlines. In fact, according to a Gallup Poll, the first time a majority was in favor of the president being removed was in a poll released on August 5, 1974, a few days after the House Judiciary Committee approved the articles of impeachment. On August 9, Nixon officially resigned.

The government's chief prosecutor didn't think Nixon knew about the Watergate break-in.

James Neal—the chief prosecutor for the trial that saw convictions for Haldeman, Attorney General John Mitchell, and Nixon's domestic adviser, John D. Ehrlichman—was unequivocal in the belief that the president did not order or know about the bugging or burglary of the Watergate hotel. His proof? "The tapes show some surprise on Nixon's part when he was told of the [break-in]," Neal told TIME. He specifically points to a tape from June 23, 1972, where Nixon asked Haldeman, "Who was the asshole that did it? Was it Liddy?" Nixon may not have known about the break-in, but he sure knew his people. Haldeman is also the one Nixon talked to about getting the FBI to back off of their investigation.

The origins of the "Watergate Salad" are still a mystery.

The famed "Watergate Salad"—a combination of pistachio pudding mix, canned pineapple, whipped topping, and chopped nuts—epitomized the mid-century obsession with desserts questionably marketed as salad. However, the exact origins of the name remain a mystery. According to NPR, there were some rumors that it was a pre-scandal staple of a restaurant inside the Watergate, but that theory never held any real weight. We do know that it shares many similarities with the equally passé Watergate Cake, which came slightly before it and combines the pistachio pudding with cake mix. But no one knows how that dish got its name, either.

The site points to a woman named Christine Hatcher, who is credited with publicizing one of the first recipes for the cake in September 1974 (she said she got it from a friend of a friend). When asked about its origins, she responded by saying, "I don't know where the recipe originated, and I don't know why it's called 'Watergate Cake' unless it's because of all the nuts that are in it!"

The National Archives tried to salvage the 18.5-minute gap from Nixon's recordings.

One of the most talked-about aspects of the Watergate scandal was the mysterious 18.5-minute gap that takes place during a 1972 recording of a conversation between the president and Haldeman in the days after the burglary. When the tapes were subpoenaed the following year and questions arose about the missing audio, Rose Mary Woods, Nixon’s secretary, testified that she had accidentally erased a portion of the recording while futzing around with a phone call (though experts cast doubt on whether or not that was even possible with the technology she was working with).

As recently as 2003, the National Archives, which maintains the tapes in a climate-controlled vault, was still trying to figure out a way to retrieve the lost recording. But all efforts to salvage audio from similar test tapes had failed (the actual tape itself was not part of the tests).

In a statement, then-U.S. archivist John Carlin said, "I am fully satisfied that we have explored all of the avenues to attempt to recover the sound on this tape. The candidates were highly qualified and used the latest technology in their pursuit. We will continue to preserve the tape in the hopes that later generations can try again to recover [this] vital piece of our history."

More than 200 scandals have -gate attached to them.

Thanks to Watergate, anytime there's a scandal, no matter how small, people tend to slap -gate at the end. Nipplegate, Tomatogate, Gamergate, Billygate, and hundreds more have entered the news cycle since the '70s. It even made its way into the Oxford English Dictionary, further solidifying its place in our lexicon. Naturally, all of these -gate scandals were topped linguistically by Gategate (also known as Plebgate), the incident in which UK politician Andrew Mitchell was accused of swearing at policemen after Mitchell was asked to use the pedestrian gate rather than the main gate to exit 10 Downing Street. (Though Mitchell later apologized for being rude to the officers, he denied using foul language and calling them "plebs.")

Discover More Stories About U.S. History

A version of this story was published in 2022; it has been updated for 2024.