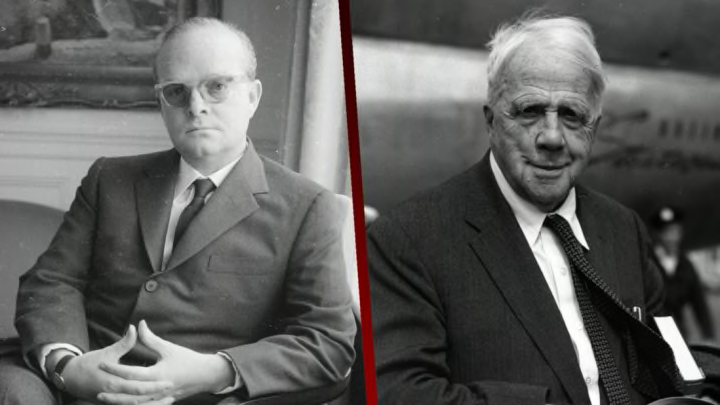

In 1942, a fresh-faced, sharp-tongued Truman Capote landed a job at The New Yorker. It wasn’t exactly illustrious: Capote, then still in high school, was a copyboy, a position that entailed ferrying other people’s copy from one place to another and generally fetching or delivering whatever anyone told him to fetch or deliver. Within about two years, Capote would be let go—thanks to one Robert Frost.

Reports of the debacle vary widely, mostly due to Capote’s penchant for embellishing anecdotes with different details for different audiences. All versions of this one, however, start out more or less the same: with a vacation to Vermont in 1944.

A Frosty Reception

Capote was attending the annual Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, organized by Middlebury College and frequented by Frost, who’d helped establish it back in the 1920s. Capote characterized it as “a glob of all these old Midwestern ladies and librarians and whatnot, oohing and ahhing and carrying on.” He went on to describe Frost as “such a ham.” In this same account, Capote explained that he planned to skip one of Frost’s poetry readings because he’d come down with the flu, but the conference director convinced him to go because Frost “was furious” that he’d declined and took it as an insult. Why they were so concerned with the movements of an insignificant copyboy is unclear, but it’s possible that Capote had downplayed his job title and played up the name of his employer.

When the venerated writer of “The Road Not Taken” and other classic poems launched into his recitation, Capote was in the audience. The event progressed without a hitch until the feverish Capote began to feel faint and sidled toward the exit. Either that, or, as he recounted in another interview, he reached down to scratch a mosquito bite on his ankle, and his “slumped over” posture gave him the appearance of having dozed off. Journalist George Plimpton reported that both scenarios were true: Capote scratched his ankle and got stuck in that position, due to a flu-induced “stiff neck.” To prevent Frost from thinking he’d nodded off, Capote made his way to the door “in this weird bent-over crouch.”

Whatever Capote’s behavior was, Frost evidently did take issue with it, abruptly halting his performance and flinging his book at Capote. (It either hit him or it didn’t; Capote has claimed both.) The disgruntled poet then said, “If that’s the way The New Yorker feels about my poetry, I won’t go on reading,” and promptly stormed out.

Copyboy No More

It wasn’t the end of the affair, but it would spell the end for Capote’s tenure at The New Yorker (at least for a little while—he’d go on to write for the publication a little later in his career). Frost penned an angry letter to New Yorker editor-in-chief Harold Ross, who reportedly fired his technically blameless copyboy. Some reports allege that Ross said, “Who the hell is this Truman Capote, anyway?” Capote, for his part, not only averred that the two were “quite friendly,” but also that Ross didn’t discharge him. Instead, Capote defended himself by explaining that as he’d attended the conference on his own time, the incident should have no bearing on his employment status. “So I left the magazine for about six months,” Capote said.

But that’s not at all what he told actress Carol Matthau. According to her, the future author of In Cold Blood actually had been sent to review Frost’s poetry reading for The New Yorker.

“He wrote exactly what he thought of Robert Frost and was fired instantly. That’s what he told me,” she said in Plimpton’s book, Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances, and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career. “He thought Frost was a big pompous ass and that it was pathetic to see everyone hanging on every word.”

While the specifics of Capote’s run-in with Frost—and the fall-out—may forever remain a little cloudy, he made his opinion of the poet himself pretty clear.