The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that shaped our modern world. Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 192nd installment in the series.

July 17, 1915: Plotting Serbia’s Demise, Second Battle of the Isonzo

After switching alliances in the prewar diplomatic chess game, Bulgaria remained neutral when war broke out, playing the two sides off each other to see which could offer more in return for its continued neutrality or active cooperation – just as Greece, Italy, and Romania were doing. But whichever side Bulgaria ended up on, its main goal was always the same: recovering the territory lost in the Second Balkan War, and especially the areas of Macedonia lost to Serbia and Greece. After the disasters of 1913 revenge against Serbia in particular became a national obsession, with Bulgaria’s Tsar Ferdinand declaring in July 1913 that, “The aim of his life was the annihilation of Serbia.”

The result was another bidding war between the Allies and Central Powers, as both sides made offers and counteroffers promising cash, arms, and above all territory to win Bulgaria’s allegiance. However the Allies were always working at a disadvantage, because they could only persuade Serbia to give up so much in order to placate Bulgaria, while the Central Powers were free to dismember Serbia completely (since that was the whole point of the war). The Allies could offer Bulgaria Turkish territory in Thrace including Adrianople, also lost by Bulgaria during the Second Balkan War, as well as Dobruja, lost to Romania, but these were lower priorities for the Bulgarians than Macedonia; they also knew that the main prize in the east, Constantinople, was already promised to the Russians.

In fact Austria-Hungary had already offered Serbian territory to Bulgaria during the buildup to war in July 1914, while Germany wooed Sofia with a big loan on easy terms, and Turkey concluded a defensive agreement with Bulgaria the following month, signaling warmer relations. But Bulgaria was exhausted from the Balkan Wars, and its domestic politics remained bitterly divided between pro-Allied and pro-Central Powers factions (despite the prewar moves towards Austria-Hungary, many Bulgarians remained attached to Russia, which had helped win the country’s independence in 1877, and the country’s elites feared German and Austrian economic domination). The Bulgarians agreed to consider limited covert operations, including support for the longstanding guerrilla movement in Serbian Macedonia, but that was it.

A number of developments prompted the Central Powers to redouble their efforts in the first half of 1915. Serbia’s unexpected victories in the early part of the war, Russia’s advance in Galicia, and Italy’s declaration of war against Austria-Hungary, all underlined the Central Powers’ urgent need to find new allies themselves. Meanwhile one crucial strategic fact dominated all other considerations: by allying with Bulgaria and conquering Serbia, the Central Powers would open communications via land with the Ottoman Empire, allowing them to send the beleaguered Turks much-needed weapons, ammunition, food, medicine, and other supplies, not to mention German and Habsburg troops to reinforce the hard-pressed Ottoman armies at Gallipoli, the Caucasus, and Mesopotamia.

Click to enlarge

Of course these setbacks served to make the Bulgarians even more leery of commitment to the Central Powers: indeed the stalemate on all fronts meant Bulgaria could afford to take its time and extract maximum concessions, as its potential contribution became more valuable. At the same time, on the other side Britain and France were still unable to force Serbia to cede territory in Macedonia in return for Bosnia (the Serbs were justly skeptical about these promises, in light of the Western Allies’ conflicting promises to Italy and Serbia in the Adriatic) and also feared alienating Romania by asking Bucharest to cede Dobruja. Sir William Robertson, the British chief of the general staff, frankly admitted, “since the war began, diplomacy had seriously failed to assist us with regard to Bulgaria.”

The situation began to change in June and July 1915, as Italy’s bloody defeat at the First Battle of the Isonzo made it clear Austria-Hungary wasn’t about to collapse, while the situation at Gallipoli stabilized and the momentous Austro-German breakthrough on the Eastern Front made Russia look more vulnerable than ever. Where the Central Powers had looked close to defeat in spring 1915, by that summer the tables had turned. Berlin and Vienna also informed the Bulgarians they were planning an attack on Serbia for sometime in fall 1915 – with the strong hint that the Bulgarians should commit now or risk losing the spoils in Macedonia.

After complex, protracted negotiations with both sides, in a secret meeting with the German diplomat Prince von Hohenlohe-Langenburg on July 17, 1915, Bulgarian Prime Minister Vasil Radovslav tentatively agreed to an alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary against Serbia, in return for all of Serbian Macedonia, territory in Greece and Romania if they declared war against Bulgaria, and part of Turkish Thrace (the Turks, desperate to open a route for supplies from their European allies, were willing to make these concessions voluntarily).

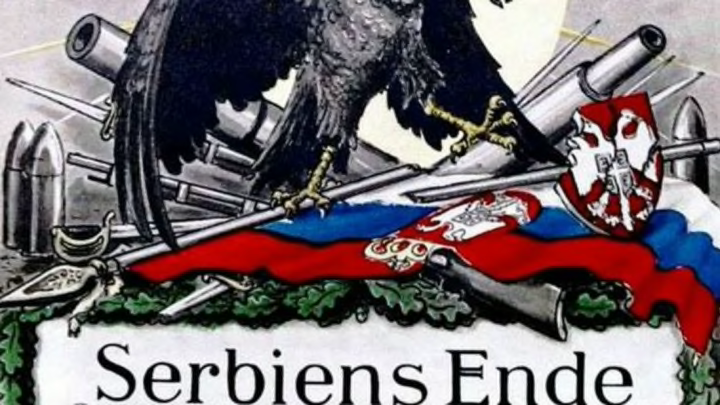

Subsequently, on August 3, 1915 Radovslav dispatched a military emissary, Colonel Peter Ganchev, to Germany to negotiate the final treaty of alliance and a military pact, which were finalized on September 6, 1915 – the same day Bulgaria concluded a separate alliance with Turkey. This military pact committed Bulgaria to join a general offensive against Serbia, alongside Germany and Austria-Hungary, within 35 days of its signing. The outcome was never in doubt: Serbia, faced with overwhelming force on all sides, would be completely annihilated (top, detail from a German postcard celebrating Serbia’s fall; full postcard below).

Second Battle of the Isonzo

The day after Bulgaria agreed to join the Central Powers, Italian chief of the general staff Cadorna launched his second major offensive against the Austrians in the Isonzo River Valley to Italy’s northeast. Unsurprisingly, using the same tactics on the same ground produced the same result as the First Battle of the Isonzo – small advances at an astronomical cost in human lives lost. However this time the Italians moved forward a few kilometers and inflicted more casualties than they suffered, so it was counted a “victory.”

The Italian Army’s mobilization continued slowly throughout June and July 1915, increasing its total active numbers from around 900,000 men to 1.2 million men, although there were only enough supplies for about 750,000 of these. This enabled Cadorna to move up 290,000 fresh troops to bolster the strength of the four Italian armies (which numbered around 385,000 men following the First Isonzo) strung out along the nearly 400-mile-long front, twisting in an “S” shape from the Alps in the west to the valley of the Isonzo in the east.

All along the front, Italian troops faced grueling journeys through rough terrain just to get into position, with marches often conducted at night to avoid enemy artillery fire. Of course this presented its own perils, as one Italian soldier, Virgilio Bonamore, wrote in his diary entry on July 5, 1915, which mentioned a chilling order soldiers had to obey even as they plunged to their deaths:

If God preserves me, I shall never forget this long night-time march at an altitude of 1,800 metres. There is something epic about our cautious approach in the dark, in total silence. Now and then, in the more difficult passes, someone falls off the edge. They fall without making a sound, as we have been ordered. All we hear is this pitiful sound of a body with a rifle hitting the ground.

With the reinforcements in place, the Second Battle of the Isonzo opened at 4 am on July 18, 1915 with a furious artillery bombardment targeting a 20-mile stretch of Austrian defensive positions on the other side of the Isonzo River, followed that afternoon by a charge of 250,000 Italian infantry against 78,000 Habsburg defenders. The barrage succeeded in destroying the Austrian frontline trenches in many places, and at 1 pm infantry from the Italian Third Army under the Duke of Aosta managed to capture enemy positions on the strategic heights at Mount San Michele, on the western edge of the Carso Plateau. However a desperate Austrian counterattack pushed the Italians out of the trenches on July 21, and after changing hands several more times on July 26 the mountaintop remained under enemy control.

Meanwhile the neighboring Italian Second Army made scant progress in multiple attacks north of Gorizia on Mount Sabotino and surrounding hills, although they did seize control of Mount Batognica at steep cost. Bonamore, occupying a captured enemy trench near the town of Caporetto, described the scene a few days later:

On the 29th I spent 24 hours in the trench, squatting among the corpses of men from both sides. The stench was unbearable. On top of that we had to endure a ferocious enemy assault, which we have repelled. Many of our men fell, hit in the head as they poked out of the trenches to fire. I haven’t eaten or drunk anything for two days. The stench from the corpses, the cold, the incessant rain, the lack of sleep – which is rendered impossible by the continual alarms – have reduced me to a pitiful state.

The Second Battle of the Isonzo would continue until August 3, 1915, with scarcely any significant changes in strategic situation. This meager victory cost the Italians 41,800 casualties, versus 46,600 for the Habsburg forces.

Despite the incredible bloodshed, men on both sides could still appreciate the aesthetics of their environment, although this was tempered by the privations of the elements and war itself. Of course few soldiers actually wanted to be there, and the natural beauty of the landscape was small consolation for their suffering. Michael Maximilian Reiter, an Austrian lieutenant stationed above the Isonzo, wrote in July 1915:

We are all waiting, waiting. What is it that every soldier at the front is really waiting for? Is it for the Italians to come swarming suddenly across the hillside? No. The thought uppermost in every mind is, when can we return home? At midnight, I do my rounds for the second time: my company is perched awkwardly on the lofty rocks above the valley, and I frequently have to crawl on all fours to reach the furthest outposts. Other times I slide down on the seat of my trousers: every now and again I stop for a rest. Far below stretches the shining blue strip of the Isonzo: above my head, tens of thousands of stars: around me, a great stillness, broken only by the clicking of crickets. The overall peace is only broken from time to time by the bursting of a shell, near or far, bringing me suddenly back from my reveries to the war… Now above the far peak of the mountain there appears a dim glow of light, gradually increasing in size and intensity and lighting up the whole valley: the moon is rising at last… I begin to dream again, to feel the soft summer night all round me, to study the Milky Way with its shining path of tiny stars across the heavens. Pictures of home drift across my consciousness, my family, my dog, my horses… Suddenly a barrage of shots breaks out without warning, wrenching me back to the battlefield.

British Set Off Giant Mine

Elsewhere minor skirmishes continued along many portions of the Western Front, producing thousands of casualties on both sides even during relatively quiet periods. However “quiet” was not the word to describe what transpired in the wrecked village of Hooge, southeast of Ypres, on July 19, 1915: frustrated by a German strongpoint built near the ruins of the Hooge chateau (an aristocrat’s manor house), the British blew the whole thing out of existence with the biggest mine used in the war so far.

After five and a half weeks spent digging two tunnels about 60 meters long under no-man’s-land, using pumps to clear the waterlogged clay, the 175th Tunneling Company of the Royal Engineers packed the ends beneath the German lines with 5,000 pounds of ammonal, a high explosive, as well as gunpowder and guncotton. A German shell severed the detonating wire at the last second, but the gap was repaired and the mines detonated at 7 pm on July 19 (below, the mine crater).

William Robinson, an American dispatch rider volunteering with the British Army, described the explosion:

When the mines were set off we saw a sight such as one observes only once in a lifetime. The earth trembled, a low, growling rumble ensued, then a mighty crash, and the air was filled with smoke, flame, bricks, dust, flying bodies, heads, legs, and arms. Our fellows let out a mighty cheer and charged across the crater formed by the explosion. The Germans seemed stunned by the awful sight they had witnessed, and we took several lines of trenches from them with very little trouble.

Alexander Johnston, a British supply officer, recalled:

… the explosion was certainly an extraordinary sight, an enormous cloud of debris and smoke went hundreds of feet into the air, and though we ourselves were about 800 yards away the whole ground shook under us. The assaulting company were told to wait for 40 seconds to enable bricks and debris to come down, and they rushed forward.

Despite this caution, ten of the advancing British soldiers were accidentally killed by falling debris. The explosion left a crater about 120 feet wide and 20 feet deep, with displaced earth forming a lip adding another seven feet above the ground. Ironically, later in the war the crater was used as a sheltered position for dugouts (above). Today the crater has filled with water and the resulting pond is a tourist attraction (below).

See the previous installment or all entries.