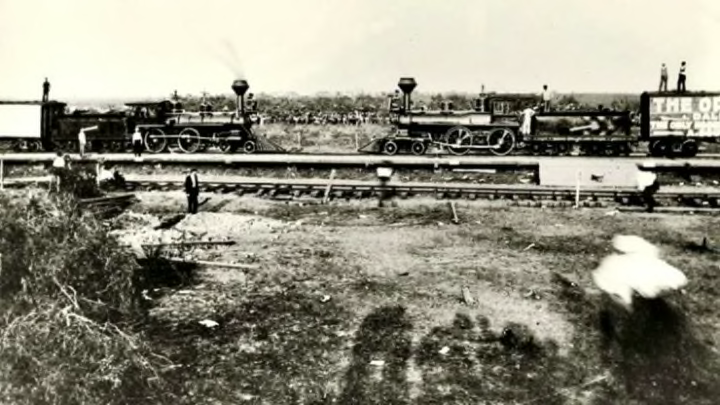

On September 15, 1896, two locomotives traveling at speeds upward of 50 miles per hour smashed into each other in Crush, Texas—completely on purpose—killing two people and seriously injuring at least six others.

The intentional collision was the brainchild of William George Crush, the general passenger agent of the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad and friend of P.T. Barnum. Though watching the spectacle was technically free, there were plenty of other ways for Crush and enterprising entrepreneurs to make money off of the deal. First of all, the M-K-T charged $2 for every round-trip train ticket to the spectacle site. A restaurant served people from beneath a Ringling Brothers tent; other diversions included a midway, cigar stands, and medicine shows.

When it came down to the main event, two train crews got the 35-ton locomotives started, then opened the throttles, tied the whistle cords down, and jumped off, leaving the massive six-car trains to smash into each other. As you might suspect, there were repercussions to causing a purposeful collision of two large locomotives. Although mechanics had assured the organizers otherwise, the steam boilers on each train exploded on impact.

The blast was immediate and deadly. The 40,000 spectators had been required to observe the collision from a hill 200 yards away, but they weren’t safe from the flying wood and iron debris. A 10-pound section of brake chain hit a teenager named Ernest Darnell directly in the head, almost splitting it in two. A young girl was struck by a chunk of iron that fractured her skull; she died on the way home. And official event photographer Jarvis Deane took a bolt to the eye. Miraculously, he didn’t die—and reportedly even stood up and instructed his photographer brothers to take photos of the aftermath.

Despite the carnage, the event was considered a success. Crush was fired immediately after the event, but after the publicity (and sales receipts) began to roll in, he was rehired. Train collisions became main events at state fairs across the country, and Scott Joplin wrote the “Great Crush Collision March.”

Crush, Texas, no longer exists today—it was deemed a town just for the purposes of hosting the event—but you can visit the site, memorialized by a marker in what is now the town of West, Texas.