Whatever your elders might tell you, violence in popular entertainment is nothing new. The people of early modern Europe frequently wove blood-soaked tales of murder, rape, and other crimes into popular songs that were sung merrily in the streets, at markets, and at fairs. In Savage Pastimes: A Cultural History of Violent Entertainment, historian Harold Schechter notes eight better-known examples that have been collected in the Norton Anthology of Poetry, including tales of family members beating each other to death, women murdering their children, poisonings, drownings, necrophilia, and "a trio of carrion birds contemplating the bloody remains of a slain knight” (in a ballad known as “The Three Ravens”).

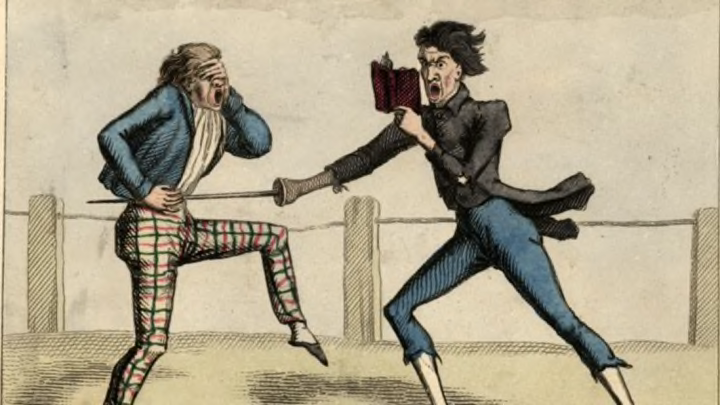

And it didn’t take long after printing was invented for these crime ballads to be set into type. Schechter notes that by Shakespeare's day, traveling peddlers had begun selling printed versions of popular ballads set onto large sheets of paper known as broadsides, which were often adorned with woodcuts depicting scenes from the crimes. (Not all broadsides were bloody: others related political events or strange and wondrous occurrences, functioning as a sort of Elizabethan version of The Weekly World News.) The most gruesome ballads were always the best-sellers—reflecting an early example of today’s saying in journalism, “If it bleeds, it leads.”

One particularly interesting subsection of the crime or murder ballad genre is the execution ballad—detailed, gory stories of rape and murder that end with the criminal dying at the scaffold (or by other state-sanctioned means), and were often sold on the day of the execution. In a recent post on The Conversation, Una McIlvenna, a lecturer in Early Modern Literature at Queen Mary University of London, notes that execution ballads were meant as a warning to the public: “If you’re going to practice capital punishment as a deterrent,” she writes, “… there’s no point doing it unless as many people as possible can find out about it.” But, she notes, “In the early modern period, the majority of the European population was illiterate, and so more creative ways of broadcasting the horror were needed.” Enter the execution ballad.

Execution ballads were often set to well-known tunes, McIlvenna notes, since familiarity increased the likelihood that people would pay attention and perhaps even sing along. Familiar rhythms and melodies also helped the ballads to be memorized, which was part of the point of these tragic tunes in general—they were much easier to remember than an entire news article. McIlvenna notes the example of Edward Coleman, a courtier executed for his supposed role in a fabricated plot to murder Charles II. Coleman’s ballad was set to the popular tune of “Packington’s Pound,” and one of its verses went as follows:

To the place of Destruction t’encounter grim death, And there by a Cord to resign half his breath:His Bowels rip’d out, in the flames to be cast,His Members dissever'd on Poles to be plac'd:A sight full of horror, but yet it's most justThat they shou'd first bleed, that after blood thirst.

Another cheery ballad, this time set to a country dance tune, concerned Catholic heretic John Felton, who was quartered (chopped into four pieces) and had his severed limbs displayed on the gates of London:

His quarters stand not all togetherBut ye mai hap to ring them thetherIn place where you wold have them beThen might you doe as pleaseth ye.For whye? they hang,Unshryned each one upon a stang:Thus standes, the case,On London gates they have a place.His head upon a poleStands wavering in ye wherling wynd

If this seems uncommonly gruesome, remember that these were the days when executions were basically a street party. As McIlvenna notes, "Not only would crowds gather at the gallows, but spectators would gather all along the journey from the prison to the execution site to jeer at, pray for, and sing with the condemned." Printed execution ballads might have functioned as something of a souvenir.

Not surprisingly, the execution ballads often included a strong element of moralizing. The condemned was always portrayed as guilty, and in British ballads at least, there was a heavy emphasis on their tortured inner life (German ballads tended to focus more on the piteous pleas of the victims). Often, the ballad would include a brief recounting of the criminal’s life story, beginning with “gateway sins”—such as not attending church or gambling—before leading up to the more serious travesties.

Many execution ballads also adopted a kind of ventriloquism, and were narrated in the voice of the murderer. These could promote a kind of sympathy for the criminal, presumably meant to help one better to absorb their message of repentance. As scholar Joy Wiltenbug notes, the first-person ploy was particularly effective if the ballad was written as a kind of farewell from the condemned in between their sentencing and execution, a “last good-night.” Several ballads related to the infamous Red Barn Murder in England (in which a man shot his lover in cold blood in a barn) took this format, including ballads known as Wm. Corder and The Murder of Maria Marten.

Whether written from the point of view of the criminal or from the third person, the execution scene was always the ballad’s crowning moment. It was a time for recounting and reflection, anguish and grief—for the victims, for the condemned, and for the shame of their situation. Often these emotions would culminate in an overwhelming display of repentance, with the condemned crying, begging God for mercy and warning others not to follow their own mistakes into a life of sin and crime. The ballad of “Mournful Murderer” George Gadesby, executed for killing his wife in 1697, is one example of such repentance: "Good Lord, I sigh and grieve/No tongue is able to express/my mournful misery/With melting tears do I confess/tis just that I should die.”

The more general murder ballad format eventually migrated to America and went on to influence the popular music of the 20th century, from 1950s hits to Nick Cave. But the more stylized and specific execution ballads are particularly interesting for what they tell us about historical crime, punishment, and the wages of sin. Whether poignant or comic, the message was always the same: be good, because evil will be punished.