A few hours before Frank Buckland was due to give a lecture at the Brighton Aquarium in May 1874, his nephews came to call. They would not have been surprised to find their uncle cooking—in fact, as they passed the small menagerie of monkeys, parrots, and other caged animals that lived in Frank’s home, they might well have spotted his dish's main ingredient: an old rhinoceros, which had been a resident at the local zoo before its recent death. Frank had spent the day slicing up the animal to make a giant meat pie for his audience.

Though the dish was intended for Frank’s admiring public, he’d made enough to offer the boys a small sample. Despite its exoticism, the meat tasted familiar, they said—like tough beef.

Frank’s dietary habits were adventurous—a tendency he inherited from his father, William. Both men were accomplished (if not always respected) naturalists who left a huge mark on early zoology. But they also sampled some rather unusual meats, including giraffe, panther, and boiled elephant trunk.

Today, eating such meats isn’t just frowned upon; in many places, it's illegal due to conservation laws. But the attitude of the Victorian age was much different. Animals were, as Frank put it, “destined to multiply and to serve ... the behests of man.” No matter how scarce it was, any creature could serve as food. As William Buckland himself once declared, “The stomach, sir, rules the world. The great ones eat the less, and the less the lesser still.”

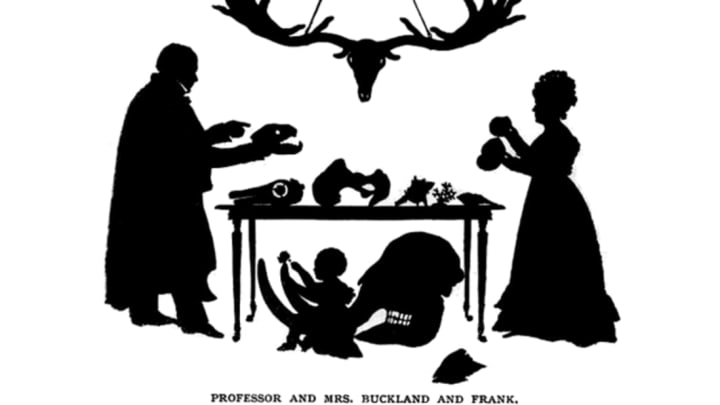

LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON

Frank grew up in a household dominated by the scholarly fascinations of his father, an Anglican minister with a deep love for earth science. William Buckland’s passion had begun at a very young age: Born in 1784, he grew up near the quarries of Axminster, which were teeming with fossils. With a little help from his father, Charles Buckland, young William would gleefully gather prehistoric shells and other treasures like wild bird’s eggs.

William became an ordained Anglican priest and, in 1808, earned an M.A. from Oxford. Afterward, he spent a few years exploring the English countryside, gathering bags of fossils. He landed a dream job in 1813 when his alma mater named him professor of mineralogy. Thus began Buckland’s impressive climb up the academic ladder; in 1845, he was appointed the Dean of Westminster Abbey, a post he held for 11 years.

Throughout his career, Buckland Senior had a real knack for making huge discoveries. In 1823, the geologist dug up Britain’s oldest known human remains; one year later, he became the first person to scientifically describe a dinosaur. He also coined the word coprolite, which means “fossilized dung,” and owned a coprolite-covered table top.

Today, William Buckland’s personal quirks are remembered in greater detail than many of his accomplishments. He and his son owned a pet bear, for example, which they dressed in a cap and gown and took to wine parties around Oxford. And every class was a performance: Lively and theatrical, the man would keep his pupils wide awake with the aid of grandiose props like a large hyena skull.

The Buckland dinner table was no less entertaining. William popularized an offbeat diet he dubbed zoophagy, which basically meant that the minister ate any creature he could get his hands on. Bear, crocodile, and hedgehog were all regular parts of the family diet. Unsuspecting guests learned the hard way that their host didn’t always bother to identify the main course by name before everyone started digging in. Still, at least one of William’s friends appreciated these bizarre meals. “I have always regretted [the] day,” wrote critic John Ruskin, “… on which I missed a delicate toast of mice.”

Apparently, though, there were still a few creatures that even William’s adventurous palate found repulsive: common mole was awful, he said, but blue bottle fly may have been even worse.

FROM THE AUTOPSY TABLE TO THE DINNER TABLE

Born in 1826, Frank was the eldest of William and Mary Buckland's nine children (only five of whom survived to adulthood), and he was very much his father's son. By 4, he could already identify fossils with ease: When a friend of his father's brought a few bones to the Buckland home, Frank correctly recognized them as the “vertebrae of an Ichthyosaurus,” a type of Mesozoic reptile that resembled a dolphin. His love of bones continued into adulthood; he loved collecting body parts from an assortment of species, and once, when a boy with an unusually shaped head walked past, Frank muttered, “What I wouldn’t give for that fellow’s skull!”

Frank’s career followed an odd path. In 1851, he put his interest in anatomy to good use by becoming a surgeon—but his love of nature far outweighed his esteem for the medical field. In 1852, the 25-year-old Buckland published “Rats” in the literary magazine Bentley’s Miscellany; readers were captivated by Frank’s lively writing style. Accessible and entertaining in almost equal measure, “Rats” was so warmly received that the publication asked Frank to pen a regular column, which would be collected into a volume called Curiosities of Natural History.

Soon, Frank had established himself as the United Kingdom’s most popular science communicator—the Bill Nye of his time, if you will. Like his father, he was a masterful lecturer. According to one journalist, “Few have excelled him in the power of conveying at once information and amusement. He inherited from his father the faculty of investing a subject, dry in other hands (and how dry lectures often are!), with a vivid, picturesque interest.” Before the year 1852 wrapped up, Frank retired from surgery to concentrate on writing, lecturing, and natural history full-time.

Of course, William’s adventurous appetite rubbed off on Frank. Nowhere was this fact more apparent than at the Royal Zoological Garden (today’s London Zoo). When a display animal died, Frank was usually on call to perform an autopsy. As he was dissecting, he gave the staff explicit instructions to save any and all remains that seemed appetizing. There was just one rule of thumb: “If they look good to eat, they are cooked; if they stink, they are buried.”

This system worked well. Over time, Frank checked off such entrées as viper, roast giraffe, bison, and a “whole roast ostrich.”

Frank preached what he practiced and proudly evangelized zoophagy. In 1860, he helped found the Acclimatisation Society of Great Britain , serving as its first secretary. The primary purpose of Acclimatisation Societies—which had also turned up in France, New Zealand, and the U.S., among other countries—was to introduce foreign plants and animals to new ecosystems. This is how starlings made the leap from Britain to America, where they are now considered invasive, and how rabbits ended up wreaking havoc in Queensland, Australia. Zoophagy was a big part of the acclimatisation platform; Frank’s group hoped to transform odd or foreign meats into familiar household staples.

To that end, on July 12, 1862, the British Society’s inaugural dinner was held in London. Attendees were served sea slug and deer sinew soup (both of which Frank called “glue-like”), kangaroo stew (“not bad, but a little gone off”), Syrian pig, Algerian sweet potatoes, and various ducks. Delighted by this exotic spread, Frank approvingly called the event “one of the most agreeable dinners … I ever was present at.”

AN ECCENTRIC LEGACY

By the standards of their day, William and Frank Buckland were considered eccentric—a reputation that has only grown with time. In The Secret History of Oxford, Paul Sullivan says that the pair "were two of the most colorful characters ever produced by the university," and the book Marylebone Lives: Rogues, romantics and rebels. Character studies of locals since the eighteenth century, edited by Mark Riddaway and Carl Upsall, called Frank "one of those true Victorian oddballs" who today "would most likely be starring in some animal-based reality show on Channel 4."

But then again, Marylebone Lives notes that Frank was "England's foremost naturalist," an opinion shared by science historian Allen Debus, who called Frank "one of Great Britain's foremost promoters of natural history" in his time. And Shelley Emling writes in her biography of early paleontologist Mary Anning that the elder Buckland was "the kind of man people were instinctively drawn to ... Graced with an agile mind, he was a great debater and a born experimenter who couldn't have cared less about what others thought of him."

Great minds often belong to unusual people, and no pair makes that clearer than the Bucklands—a father and son who, between their odd gastronomic escapades, advanced and popularized the study of our world and the life forms we share it with.