As the passengers of many a cruise ship can attest, Norovirus is a nasty illness. When people come into contact with it—via someone else who has norovirus; by eating contaminated food or water; or by touching a surface with norovirus particles on it—and are infected, the linings of their stomachs or intestines (or both!) become inflamed in something called acute gastroenteritis. First comes the stomach pain and nausea, and then the projectile vomiting and diarrhea, which bring billions of new noroviruses into the world. That number is staggering considering the fact that just 18 particles of the virus are enough to make a person ill, and the amount of virus particles that can fit on the head of a pin can infect at least 1000 people.

Norovirus, according to Carl Zimmer at National Geographic, has “Olympic-level feats of transmission.” Each year, as many as 21 million people come down with norovirus in the United States, and between 570 and 800 die. So naturally, scientists are very interested in determining just how the virus spreads—and they're building vomiting machines to figure it out.

Vomiting Larry at the Health and Safety Laboratory in Derbyshire, England, is one; another, built by researchers at North Carolina State University, was a key part of a study released this week in PLOS One.

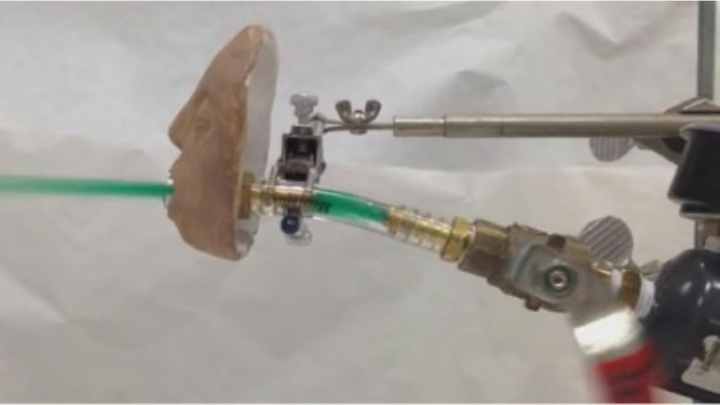

This machine, which was built at one-quarter human size, is equipped with tubes that stand in for the esophagus and mouth; a pressurized simulated stomach; valves, pistons, and pumps to create vomiting; and, of course, a sad clay face that perfectly shows what it’s like to have norovirus. (That’s not all the mask is good for—according to Science News, it “provides weight to bend the throat down, simulating the flexed neck of a heaving human.”)

During projectile vomiting, particles of vomit—and the noroviruses they carry—become aerosolized and land on surfaces, where they’re hard to eradicate (according to Zimmer, norovirus “can survive freezing and heating and cleaning with many chemical disinfectants”). In this study, scientists were interested in both demonstrating the aerosolization and figuring out just how much of the virus was present in those airborne particles—a particularly tough challenge, considering that norovirus can’t be cultivated in a lab.

The scientists created two “simulated vomitus matrices”—one with high viscosity, for which they used vanilla Jell-O pudding, and one with low viscosity, which was made with pre-gelatinized starch and simulated human saliva—and loaded them up with high and low concentrations of a norovirus stand-in called MS2. The scientists inserted 13.1 mL of the solutions into the vomiting machine’s stomach chamber and expelled it at various pressures that simulated vomiting and coughing.

After running the experiment, the scientists discovered that every vomiting trial led to aerosolization of the virus, ranging from “as few as 36 and as many as over 13,000 virus particles,” according to Science News.

Compared to the amount of virus in the vomit—most of which ended up at the bottom of the puking chamber—“the degree of aerosolization was rather minimal (<0.01 percent),” the scientists write. “However, based on human NoV infectious dose and estimated virus concentrations in vomitus, even these small percentages of aerosolization would likely result in significant disease risk.”

The higher the pressure of the vomit, the more noroviruses were aerosolized—but not always by a statistically significant amount. “This was partially due to the large standard deviations in the measurements, suggesting high variability in degree of virus aerosolization during vomiting,” the scientists write. “This implies that even a relatively minor vomiting event may have public health significance.”

Given all of this information, you might be asking yourself: Is there any way to prevent norovirus? The CDC recommends thoroughly washing not just your hands, but also fruits and vegetables, and thoroughly disinfecting surfaces with a bleach solution (5 to 25 tablespoons of bleach per gallon of water should do the trick). Keep sick people away from your food—and if you’re unlucky enough to get sick, don’t prepare any food yourself.

[h/t Science of Us]