The tiny European country of San Marino—a 24 square-mile enclave that, like Vatican City, is entirely surrounded by Italy—is named after its founder, St. Marinus of Dalmatia. Marinus was a stonemason by trade, who moved to Italy from Dalmatia (modern-day Croatia) to help reconstruct the city of Rimini on Italy’s Adriatic coast. When he arrived there, however, Marinus found that his religious beliefs made him a target of the Roman Empire’s on-going persecution of Christians, and he had little option but to flee the city. Ultimately, 10 miles inland, he established his own dedicated Christian settlement in September 301 AD, and the Republic of San Marino, which grew from that settlement, has remained independent ever since. Today, it is considered the oldest sovereign nation in the world.

The five countries listed here represent San Marino's extreme opposite—far from being the longest-surviving nations in the world, they all declared their independence (with varying degrees of success and recognition) before disappearing from the world map less than a year later.

1. CALIFORNIA REPUBLIC

FreeDownloads // CC0 1.0 Universal

In the summer of 1846, a band of American settlers in what was then the Mexican territory of California staged a rebellion challenging Mexico’s control of the region. On June 14, more than thirty rebels invaded a Mexican military outpost at Sonoma and placed the general and his family there under arrest. A white sheet was found, and on it was drawn a five-pointed star and a crude drawing of a grizzly bear—this makeshift flag was then raised, and the independent California Republic was declared.

With the so-called “Bear Flag Revolt” a success, one of its instigators, John C. Fremont, took command of the group on July 1 and began an occupation of San Francisco. Just six days later, however, word spread that American army forces had marched on Monterey further south and had hoisted a United States flag, effectively establishing California as a new American territory. As this had been the goal of the rebellion in the first place, the new government had little reason to maintain its sovereignty and so, just over three weeks after it was declared independent, the California Republic was disbanded.

2. WEST FLORIDA

Pumbaa80, Wikimedia Commons

Originally part of the Spanish American province of New Spain, West Florida encompassed a narrow stretch of land on the Gulf of Mexico, bounded by the Mississippi and Perdido Rivers in the west and east, and by the 31st parallel in the north. The coastal cities of Biloxi and Mobile all lay within its borders, as did Baton Rouge—where, on September 23, 1810, a garrison of Spanish troops was overthrown by American settlers who declared West Florida an independent republic. Fulwar Skipwith, a diplomat who had been involved in the Louisiana Purchase, became the country’s first and only governor.

The rebellion was sparked by Spain’s reluctance to agree that West Florida had been included in the Louisiana Purchase, and its subsequent unwillingness to relinquish the province to the United States. President James Madison meanwhile maintained that the land had been included in the purchase, and thus was neither Spanish nor independent territory, but rather a constituent of the United States. In October, he sent the governor of the neighboring Territory of Orleans to meet with Skipwith to resolve the situation, and although Skipwith initially demanded that West Florida be accepted into the Union as a state in its own right, he ultimately agreed to its annexation by Orleans. The territory was eventually divided between Louisiana and Alabama.

Although the nation of West Florida was short-lived, its flag wasn't; it's believed that the star it featured inspired both Texas' state flag, as well as California's flag during the state's rebellion. (A star still appears on the modern-day California design.)

3. ACRE

Giro720, Wikimedia Commons

Acre is a landlocked region of South America located roughly where Brazil, Bolivia, and Peru meet 500 miles inland from the Pacific coast. Originally a Bolivian territory, Acre has declared its independence three times in history, but has never once survived longer than a year. First, in 1899, a Spanish diplomat named Luis Gálvez Rodríguez de Arias seized power in Acre after seeing just how wealthy the region had become during a boom in rubber production. Galvez declared himself President of the First Republic of Acre in July 1899, and renamed the state capital “Arieopolis” in his own honor; he remained in control until March 1900, when invading Brazilian troops arrested Gálvez and returned the area to Bolivia.

Just months later, in November 1900, a Second Republic of Acre was declared, but it too was soon quashed and Bolivia regained control just four days after independence. A final, much more organized attempt—backed by an army of 30,000 revolutionaries and led by former Brazilian soldier José Plácido de Castro—led to the establishment of the Third Republic of Acre in January 1903. But after a series of indecisive clashes with Brazilian forces, a peace treaty was signed in November that handed Acre over to Brazil in exchange for cash and the construction of a new road that would better link Bolivia to the outside world. To this day, Acre remains one of the twenty-seven constituent states of Brazil.

4. EZO

Zscout370, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0

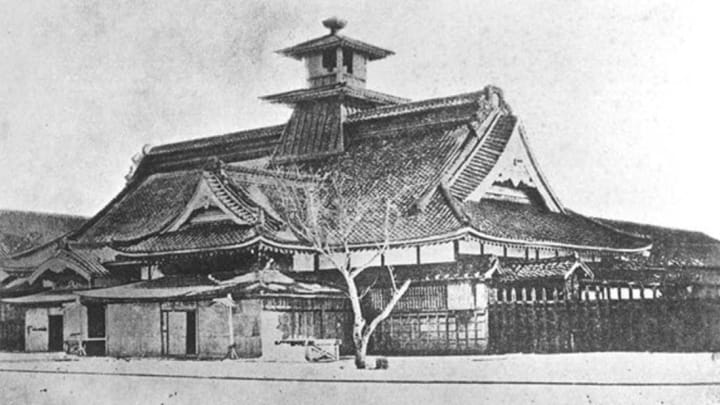

The Boshin War was a Japanese civil war fought between Japan’s last traditional feudal government, the Tokugawa Shogunate, and an alliance of modernist Japanese forces looking to restore and reinforce the ruling power of the Imperial Court in Kyoto. The war rumbled on for just over a year, from January 1868 to May 1869, when the Tokugawa were finally defeated and Imperial rule in Japan was re-established. But in the final months of the war, with defeat seemingly inevitable, many surviving Tokugawa forces had fled north to the island of Ezo (now Hokkaido). On January 27, 1869 they established their own republic there with the shogun’s naval leader, Admiral Enomoto Takeaki, elected as sosai, or president. Remarkably, Ezo’s was the first democratic election ever held in Japan.

President Enomoto reportedly pleaded with the newly restored Imperial government in Kyoto to allow the new Republic of Ezo to survive and maintain its traditional Japanese system, but his requests were turned down. As Imperial forces strengthened on the mainland, Ezo was invaded in April 1869 and, after several brutal clashes, Enomoto surrendered on June 26. The Republic of Ezo had lasted just 150 days.

5. KINGDOM OF CORSICA

Moipaulochon, Wikimedia Commons

From the late 1200s to the mid 1700s the Mediterranean island of Corsica was a constituent of the Republic of Genoa, in modern-day Italy. The Corsican people, however, were so unhappy with Genoese rule that by the early 1700s a movement to establish Corsican independence had gained considerable momentum. Entirely by coincidence, at around the same time an eccentric German adventurer named Baron Theodore von Neuhoff arrived in Genoa. (To briefly recap Neuhoff's extensive C.V., at this point, he had already served in the French and Swedish armies; been employed in the court of King Philip V of Spain; married and then abandoned one of the Queen of Spain’s ladies-in-waiting; abducted a nun; and been forced to disguise himself as a monk). Once in Genoa, Neuhoff happened to meet a band of Corsican rebels, who either convinced him or else allowed him to convince them—depending on whose story is to be believed—to return to the island to help establish it as an independent state. Neuhoff arrived there in March 1736, and was promptly crowned King Theodore I. His rule, however, was short-lived: by challenging Genoese power, Neuhoff became an enemy of the Genoese state, and as his questionable reign as King of Corsica began to crumble, he fled the island in November. Corsica quickly fell back under Genoese control—while Theodore went on to be arrested for debt in Amsterdam.

Two much more successful attempts at Corsican independence followed. In 1755, a Corsican Republic was declared by a local statesman, Pasquale Paoli, and remained in place until the island was annexed by France in 1769. Twenty five years later, British forces helped to expel the French from the island, and in 1794 an Anglo-Corsican Kingdom was established—but it too collapsed when the French troops returned two years later. The island has remained under French control ever since.