Bacteria are not the enemy. That’s the first thing microbiologist and doctor Nicola Fawcett wants us to know. The microbes are an essential part of our bodies and our lives. “We wouldn’t be able to survive in this world without bacteria,” she wrote in her blog.

Fawcett studies the bacteria she finds in the poop of her patients and study participants. In her work with the Antibiotic Resistance in the Microbiome OxfoRD study, which has the best recruitment posters ever—

—Fawcett watches patterns emerge. She sees how diet, travel, hospital stays, and, most dramatically, antibiotic use change a person’s microbiome. Our gut bacteria are like plants in a garden, she writes:

A healthy gut is one that is populated with many different types of bacteria, living together. Some bacteria are almost always beneficial, some are harmless, and some can be harmful. They compete for nutrients, interact, and communicate with one another. But much like a garden, some types of bacteria can get out of control and cause damage if the careful balance between human and bacterial community [sic] is disrupted.

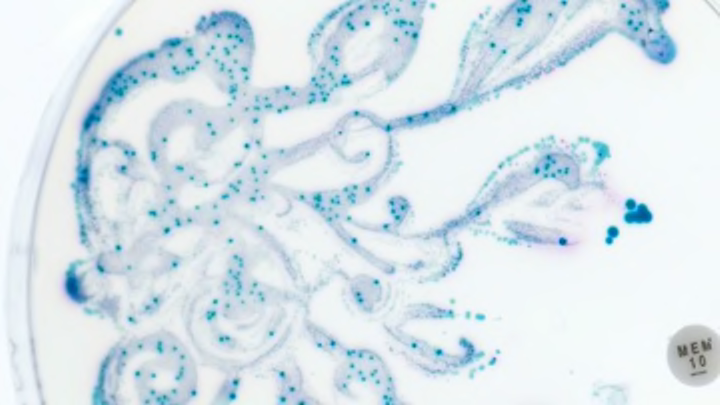

With these botanical images in mind, Fawcett decided to create images that would showcase the beauty, interconnectedness, and complexity of gut bacteria. She stamped tiny colonies of bacteria onto a dish of dye-infused agar, then left them to grow overnight. The dyes can only be activated by the enzymes of specific bacteria; in this case, it was Escherichia coli (purple), Citrobacter (turquoise), and Klebsiella (dark blue).

Each colored dot represents an entire colony of bacteria, which could be made up of millions of individual organisms. The colonies grew and merged, with sizeable populations of E. coli and Citrobacter crowding out the tiny outposts of Klebsiella growth. From the seed colonies Fawcett had planted in the gel, the bacterial growth flourished, unfurling into a jewel-toned, translucent likeness of ivy on the vine.

At the outer edges of the gel, Fawcett stuck discs full of antibiotics. The antibiotics seeped into the agar and spread, killing off colonies of E. coli and Citrobacter. A halo of empty space surrounded the disc marked MEM, for Meropenem—medicine’s current ‘last line of defense’ against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. But a few hours later, the halo had all but disappeared. In the absence of competition, Klebsiella colonies had crept in.

The presence of Klebsiella in what should be a bacteria-free zone is meant to convey “a worrying message,” writes Fawcett:

Modern medicine (including surgical operations and cancer treatment) depend [sic] on having effective antibiotics to protect people from infection. These are already running out.

Fawcett submitted photographs of her bacterial paintings to the American Society for Microbiology (ASM)’s 2015 Agar Art contest. (Winners will be announced next week.) The project was a lot of fun, she said,

and a surprising amount of work. You know the old showbiz adage, ‘never work with children and animals?’ I sort of feel the same way about bacteria…they seldom behave the way you want them to.

All photographs courtesy of Chris Wood, Oxford Medical Illustration, and Nicola Fawcett.