Renowned neuroscientist and author Oliver Sacks passed away in his New York City home this summer at age 82, but his legacy of empathy will live on. In honor of Sacks’s life and work, the science publisher Elsevier will make a selection of his academic papers accessible for free beginning December 1.

After completing his studies in his native England, Sacks came to the U.S. and began a career as a researcher. He soon learned that research was not for him. “I lost samples,” he said in a 2005 interview. “I broke machines. Finally they said to me, ‘Sacks, you’re a menace. Get out. Go see patients.’”

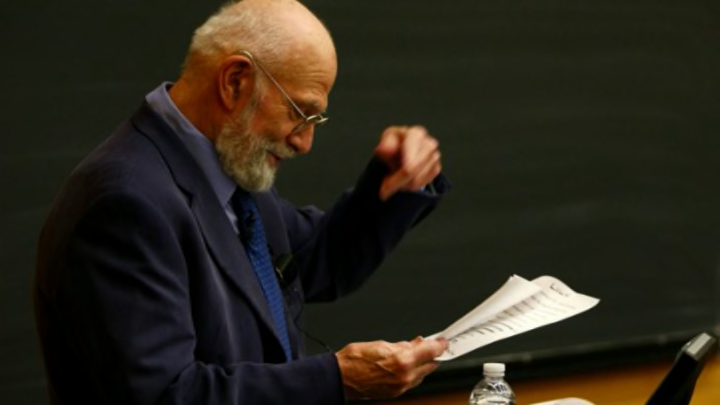

And he did. Sacks saw his patients through a lens of curiosity and care—and he wrote about them, bringing their stories and lives to the public. Each of his “neurological novels,” as he called them, invited viewers into the experiences and struggles of his patients. His unique perspective and lyrical narratives made books like The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Awakenings popular bestsellers, and many were adapted for stage and screen.

The neuroscientist defied categorization and specialization in his work, instead pursuing a huge range of subjects, including hallucinations, amnesia, swimming, pre-Columbian history, and ferns.

Sacks was beloved for his contributions to both science and literature. The New York Times called him “the poet laureate of neuroscience.” His list of honors and recognitions is lengthy. Queen Elizabeth II appointed him Commander of the British Empire. Sacks even had an asteroid named after him: 84928 Oliversacks.

By the end of his life, Dr. Sacks was receiving about 10,000 fan letters a year, according to The New York Times. “I invariably reply to people under 10, over 90, or in prison,” he said.

An interviewer once asked Sacks how he would like to be remembered. “I would like it to be thought that I had listened carefully to what patients and others have told me,” he said, “that I’ve tried to imagine what it was like for them, and that I tried to convey this. And, to use a biblical term,” he added, “bore witness.” To that end, among those papers is a letter written to the medical journal The Lancet condemning the treatment of prisoners in Guantanamo Bay.