Competition in the confectionary industry has always been fierce, and in the early 1900s, when the first candy bars were bursting onto the scene, it was particularly so. The success of Hershey’s milk chocolate bar, introduced in 1900, spawned numerous imitators as well as bars like Oh Henry! and Goo Goo Clusters that upped the ante by adding ingredients like peanuts, caramel and nougat. By the 1920s, the candy bar industry had become a sweet, delicious free-for-all.

To stand out in a crowded field required a good idea, good execution—and no small amount of showmanship. Nobody understood this better than Otto Schnering, founder of Chicago’s Curtiss Candy Company. In 1916, Schnering started his company, which borrowed his mother’s maiden name, and within a few years had found success with a nut-topped chocolate bar called Kandy Kake. While local sales were promising, Schnering had king-size ambitions for himself and for Curtiss. So in 1921, he reformulated the Kandy Kake bar by adding peanuts and nougat, and renamed it Baby Ruth (supposedly after President Grover Cleveland’s daughter, which, in an era when Babe Ruth ruled the baseball diamond, was probably baloney. Ruth sought royalties at one point and lost, and later the candy company actually sued Ruth for trademark infringement, and won).

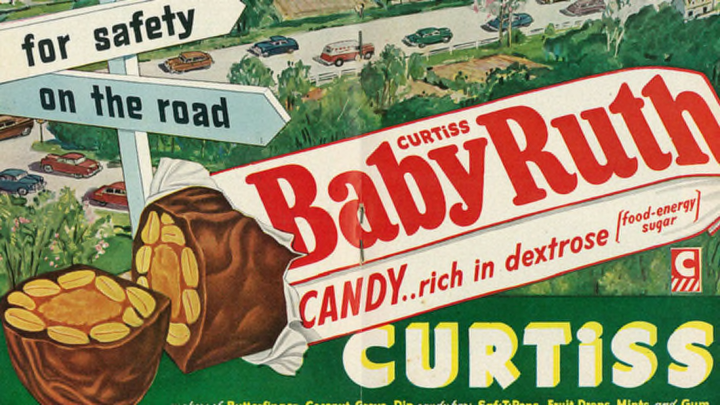

Babe Ruth ad from the 1950s. Pieces of the Past via Flickr // CC BY 2.0

To compete with the popular Oh Henry! bar, which cost 10 cents, Schnering streamlined production and began offering Baby Ruths for five cents apiece. “Everything you want for a nickel!” proclaimed the brand’s slogan. An advertising mind clearly ahead of his time, Schnering also plastered the Baby Ruth logo on consumer products—everything from matchbooks to pocketknives and beach balls—and sponsored events like circuses and hot-air balloon shows.

Schnering’s greatest bit of showmanship, arguably, came in 1923. This was at a time when aerial stunt shows called “barnstormers” were popular, with the likes of Charles Lindbergh dazzling crowds with loops, rolls and other high-flying tricks. Inspired by their popularity, Schnering contacted an Atlanta pilot named Doug Davis and proposed his own stunt. Davis agreed, and one afternoon (the exact date isn’t clear) took to the skies over Pittsburgh in a Waco biplane emblazoned with the Baby Ruth logo. According to promotional material distributed by Curtiss (and cited by Aviation Quarterly), Davis brought his plane down to just a few dozen feet over the city and began performing various tricks, including flying between buildings. After he had everyone’s attention, Davis ascended and completed the most crucial step in his mission: dumping hundreds of Baby Ruth bars, each attached to a tiny rice paper parachute, out over the city.

So what happens when candy actually falls from the sky? The Curtiss publication describes the scene: “People risked falls from windows reaching for the parachutes. Children ran out into the streets (without danger—traffic was hopelessly snarled) and adults fought for the free candy.” There could be some embellishments here, but the event clearly made an impact. Pittsburgh officials met shortly after Davis’s flight and passed an ordinance requiring planes to fly above several hundred feet over the city. They also specifically outlawed distributing candy bars from the air.

For Schnering and the Curtiss Candy Company, the stunt was a huge success. He established the Baby Ruth Flying Circus and commissioned pilots across the country to drop candy bar payloads over beaches, fairgrounds, and racetracks. To meet growing demand, Curtiss expanded its manufacturing facilities to incorporate nationwide distribution, and by 1928, Baby Ruth was the country’s best-selling candy bar.

Doug Davis, meanwhile, continued to fly in Schnering’s circus, and even ferried himself and his wife to their honeymoon in a Baby Ruth plane. Before performing his runs, Davis would often pick out a volunteer to ride with him and dump out the candy. In Miami, he enlisted a 12-year-old boy whose father was the principal distributor of Baby Ruth candy in southern Florida. The boy’s name was Paul Tibbets, and it was his first ride in an airplane. Twenty years later, as the commander and pilot of the Enola Gay, he would drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.