By the late 19th century, Americans had developed a stigma around fatness. At the same time, magazines were becoming far more influential as both their number and circulation exploded. In 1860, 575 magazines were published in the United States; by 1905, that number was 7500. With more magazines came more advertising, and with a cultural shift toward thinness as a beauty ideal, many of those ads began promising weight loss, especially in film fan magazines and other publications geared toward women. But some of the methods they proposed for “reducing” (dropping the pounds) were questionable, while others were downright bizarre—and even dangerous.

1. FATOFF

Introduced around 1909, Fatoff claimed to simply melt your fat away with “No Dieting! No Dosing! External application only!” In one 1912 ad, the supposed creator of the product, Mary Spencer Borden, gave a confusing account of its origins: “I, Mary Spencer Borden, under oath say that less than six years ago I was a monstrosity with fat and rheumatism, and I weighed over 225 pounds in the upper part of my body and my lower limbs had atrophied. […] I had tried every known remedy to reduce my fat without any success whatever until I thought of this wonderful ‘FATOFF.’ […] I cannot say I discovered it. It was an inspiration.” Department of Agriculture chemists felt differently, calling the product an “unmitigated fraud” after a chemical analysis revealed Fatoff to “consist of 10 per cent soap and about 90 per cent water.”

2. DR. WALTER’S FAMOUS MEDICATED REDUCING RUBBER GARMENTS

Made of rubber with a “medicated” coating, Dr. Walter’s garments claimed to stimulate weight loss by causing the wearer to sweat. The brand sold a garment for every conceivable problem area, including the chin, neck, waist, bust, hips, legs, ankles, arms, and hands. (Dr. Walter also offered a terrifying rubber face mask—“Excellent for bleaching the face.”)

Not only would Dr. Walter’s Famous Medicated Reducing Rubber Garments fix unsightly ankles and banish a double chin, but they even claimed to be comfortable. While wrapping your torso in rubber may not scream “comfortable” to us now, rubber girdles—Dr. Walter’s most popular product—were a welcome alternative to the classic corset, with its rigid, painful boning. Beginning in 1904, Walter submitted patents on a number of rubber garments, and she advertised her “reducing garments” in magazines like Vogue and newspapers like The New York Times from 1906 through the early 1920s. By 1922, ads touted “millions” of sales. “Reducing” corsets and girdles from various brands continued to be sold through the 1930s, serving the same purposes as today’s Spanx—except that they claimed to make you “look thin while getting thin.”

3. DR. LAWTON’S FAT REDUCER

Launched around 1921, Dr. Lawton’s Fat Reducer was a suction cup device that claimed to “dissolve and eliminate superfluous fat from the system” using vacuum massage. Designed like a plunger, it produced results in four or five days, the ads asserted, by “break[ing] down the fat tissue” through its “massage effect.” The company offered a money-back guarantee if the customer didn’t see progress after 11 days.

4. LESSER SLIM FIGURE BATH

The Lesser Company advertised its Slim Figure Bath as “the sensation of Europe,” catching consumer eyes with images of naked, frolicking women. Presented as a German invention, Slim Figure Bath ads referred to “clinical tests” by “prominent Berlin physicians” and something called “the famous Nauheim principle”—representing the brand as exotically European and playing it up as highly scientific and modern. But Slim Figure was merely one brand of bath powder claiming the magical ability to melt fat—and like its competitors Florazona, Fayro, and Every Woman’s Flesh Reducer, it simply didn’t work.

According to Carl Malmberg, author of a 1930s exposé on fad diets called Diet and Die, Lesser Slim Figure Bath was composed of corn starch, baking soda, table salt, borax, and tartaric acid (which is present in cream of tartar). It did not need to come from a German lab but could be mixed up in the kitchen. Like the ads claimed, it was “absolutely harmless,” but it was also absolutely useless as a weight-loss product, with the American Medical Association (AMA) calling it an “elaborately exploited piece of quackery.”

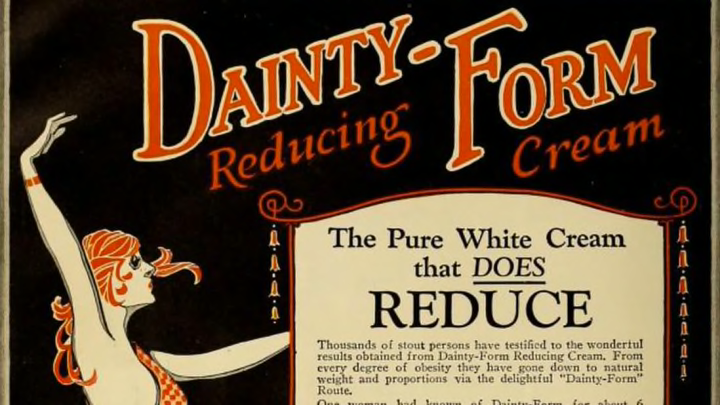

5. DAINTY-FORM REDUCING CREAM

Creams that claimed to dissolve fat were another popular product in the 1920s. In addition to Dainty-Form Reducing Cream, consumers could purchase Melto Reducing Cream, Slendaform Reducing Cream, Franco French Reducing Cream, and the specialized FLEC Ankle Reducing Cream. “Ads for passive [weight-loss] products such as pills, tea, and soap were usually aimed at women,” writes Heather Addison, a film studies scholar, in her book Hollywood and the Rise of Physical Culture. Conversely, ads aimed at men often touted exercise and promised to build muscle. Dainty-Form cultivated its feminine image, often including testimonials from Ziegfeld Follies chorus girls in its advertisements alongside images of sylphlike women.

6. LA MAR REDUCING SOAP

La Mar Reducing Soap was a coconut-oil soap tinged with potassium iodide and sassafras that claimed to melt away fat while shrinking skin so that there would be no excess skin after the weight was lost. It sold at 50 cents per bar, and customers hoping to become thin could purchase the accompanying Slenmar Reducing Brush for an additional $3. At its height, the company sold 200 to 300 soaps per day, though it reportedly spent $120,000 advertising the product against just $150,000 in annual receipts. The head of the AMA’s investigative wing called the product “unadulterated hokum,” and in 1926, it was declared a fraud by the U.S. Postmaster General and the company was barred from advertising or processing sales through the mail.

7. REDUCINE

Reducine was a “pleasant cream” that caused a “harmless chemical reaction […] during which the excess fat is literally dissolved away”—and it prompted the first-ever Federal Trade Commission case against a weight-loss product. In 1927, the FTC declared that Reducine was “useless and of no value for the purposes for which it is so advertised.” As a one-two punch against this fraudulent advertising, the FTC issued a cease and desist order to both McGowan Laboratories, which made Reducine, and a publishing company that had been running its ads in the magazine True Romances. By accepting the advertisements, the FTC ruled, the publisher had become “purposely and knowingly party to and part of a false and fraudulent plan for the misleading and deceptive advertisement and sale of a product”—an illegal act [PDF]. Cease and desist orders, as well as private agreements to shed advertising of questionable products, became key parts of the FTC's toolkit in attempting to root out sham weight-loss products in the following years.

(The “reducing cream” Reducine differed from another cream called Reducine, which was sold around the same time—and still is—as a remedy for horse lameness.)

8. WEIL SCIENTIFIC REDUCING BELT

First appearing around 1922, the Weil Scientific Reducing Belt promised to “melt away surplus fat” thanks to a “massage” action that would occur as the body moved against the “self-massaging belt.” Unlike most of the weight-loss products we’ve highlighted here, Weil’s belt was marketed primarily to men, advertising in magazines like Popular Mechanics, The Rotarian, The American Legion Weekly, and Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen’s Magazine. Even ads in female-focused movie magazines like Screenland were headlined with callouts to “Fat Men!” The belt spent more than a decade on the market, but in 1936, the Federal Trade Commission launched an inquiry into the Weil Company for fraudulent advertising claims, eventually issuing a cease and desist order for any marketing asserting that the Weil Scientific Reducing Belt could actually reduce weight or fat, build up muscle, increase circulation, increase energy, “or otherwise improve the health” [PDF].

9. SILPH REDUCING CHEWING GUM

“Just think that all one has to do to take off ugly—unsightly rolls of FAT is to chew two or three pieces of a refreshing, delightful chewing gum.” Just think! Unlike many other so-called “obesity cures,” Silph Reducing Chewing Gum actually had the power to effect weight loss—but that’s because, despite marketing claims that it “contains no thyroid or dangerous drugs” [PDF], Silph included desiccated animal thyroid that exerted a hazardous influence on the metabolism. This mid-1920s product was also laced with laxatives and poisonous pokeroot. In 1926, the Post Office issued a fraud order and banned the product from being advertised or shipped by U.S. mail.

The idea of weight-loss gum reappeared in the early 1970s with Vel-X Gum. Advertised in comic books, Vel-X was investigated by the FDA and banned in 1972 from claiming any weight-loss properties.

10. NEUTROIDS

To promote his weight-loss invention Neutroids, Dr. R.L. Graham offered a bizarre explanation of why the body produces fat. “The fat in your body is caused by a simple chemical process,” ads explained. “Yeast cells in your stomach combine with starch and sugar and form ALCOHOL. When alcohol gets in the blood, fatty tissue is made instead of healthy, lean muscle. Fat people, even though they may be TOTAL ABSTAINERS have four billion yeast cells (or more) in their stomachs—enough to make 4 ounces of alcohol a day!” The solution: Neutroids, which purportedly destroyed yeast cells in the stomach and thus prevented the body from developing fat. The ads even included a helpful visualization of the resulting “reduction in stomach yeast cells,” in the form of a sketch of what looks like piles of grain.

Of course, Dr. Graham was wrong about why the body produces fat, and while his Neutroids could potentially have caused weight loss, it was not for the reason he asserted. According to analysis by the AMA’s Bureau of Investigation, the tablets contained 50 percent iodol, which the Bureau described as “distinctly poisonous”—a substance known to cause emaciation and death if taken in significant amounts.

11. LUCKY STRIKE CIGARETTES

Beginning in 1929, Lucky Strike Cigarettes ran an ad campaign urging people to lose weight by having a smoke whenever they felt a craving for food. Marketers considered a tagline that rhymed, “[W]hen tempted to nibble remember your middle. Light up a Lucky … be smart, be slender!” They eventually settled on the simple command “Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet.” However, facing the threat of lawsuits from candy-makers, Lucky Strike dropped the word “sweet,” telling consumers to just “Reach for a Lucky instead.”

Lucky Strike ads condemned “harmful reducing girdles, fake reducing tables [and] other quack ‘anti-fat’ remedies condemned by the Medical profession,” explicitly positioning their cigarettes as a safe, doctor-approved weight-loss alternative to “ridiculous and dangerous nostrums.” Oddly enough, the company did not claim that Lucky cigarettes themselves caused weight loss, but only that the practice of having a smoke instead of a snack led to weight loss. We now know that smoking is an appetite-suppressant—and not just if you reach for a cigarette instead of a candy bar.

12. VIGOR’S HORSE ACTION SADDLE

“The best exercise for the strong, the weak, also the blind, lame or crippled”—or so it claimed—Vigor’s Horse Action Saddle promised to cure everything from obesity to hysteria. Though it may look ridiculous to us today, in 1894 the British medical journal The Lancet called the product “very ingenious.” Vigor & Co. sold multiple versions of this device, with the cheapest costing 7 guineas and the most expensive going for 21 guineas. The models meant for women came equipped with a side saddle, while the men’s versions were designed for the user to sit astride. Though you won’t find horse-riding machines at workout facilities nowadays, the devices were relatively popular in their time—the Titanic even included a motorized version in its first-class gymnasium in 1912.

13. HEMP BODI-MASSAGER

Sold during the 1930s by the Conley Company, the Hemp Bodi-Massager offered to roll your fat away. Equipped with rubber balls attached to a handle, the product claimed to massage “just like skillful human hands,” but the Council on Physical Therapy at the AMA reported that “it did exactly what, in practicing good massage, a masseur tries to avoid,” pinching the skin instead of kneading deep tissue. In 1935, the FTC blocked the Conley Company from a laundry list of claims, including any statements that the Hemp Body-Massager caused weight-loss or that it “works like magic” [PDF].