In the fall of 1881, the world was introduced to livestreaming.

Yes, you read that right: livestreaming, where we use our smartphones or other devices to transmit a live feed of what we’re seeing and hearing to people who aren’t physically with us. There’s Periscope, Snapchat, and YouNow, but before any of those newfangled apps, there was the theatrophone.

The fall of 1881 was a notable one in Paris: The City of Light was hosting the first International Exposition of Electricity off the Champs-Élysées. The expo created a buzz, with Europeans flocking to Paris to see the wonders of electricity, from Edison’s recently-invented light bulb to Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone to a little device that seemed to fuse the two together: the theatrophone.

The theatrophone was a curious thing. The concept included wires leading from a stage into a dual-channel audio system with audio for each ear. From there, the wires would transmit sound to a receiving audio source. For the Expo, 80 telephone transmitters had been set up across the stage of the Paris Opera and connected (via cables through the Paris sewers) to rooms in the Paris Electrical Exhibition. Visitors could pick up the theatrophone and hear a live performance of the opera—more than two kilometers away from the actual stage. According to the New Scientist, it was the first-ever broadcast of stereo sound.

Inventor Clement Ader, today perhaps best known for his aviation work, had previously been responsible for establishing the first telephone system in Paris—making him the perfect person to launch livestreaming.

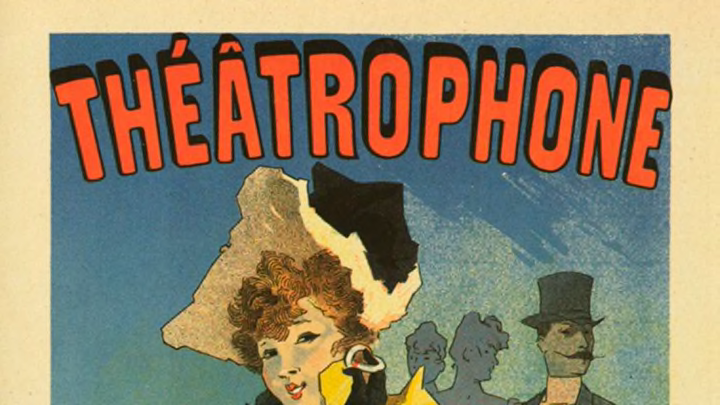

Parisians immediately took to the invention. The Belle Epoque pop artist Jules Cheret immortalized the theatrophone in a lithograph featuring a woman in a yellow dress, grinning as she presumably listened to an opera feed. Victor Hugo was intrigued:

“We went with Alice and the two children at the Postmaster Hotel. At the gate, we met Berthelot, who was coming. We went. It’s very strange. It starts with two ear muffs on the wall, and we hear the opera; we change earmuffs and hear the French Theatre, Coquelin. And we change again and hear the Opera Comique. The children and I were delighted.”

The theatrophone, and similar services, were adopted by high society across Europe. In 1884, the Portuguese King Dom Luis, a diehard opera fan, was unable to attend the performance of Laureana at the Teatro Nacional de Sao Carlos in Lisbon. But no fear: Dom Luis got his opera fill via theatrophone at his palace. He was such a fan that he backed having subscriptions for opera fans like himself (90 performances for 180,000 Portuguese reis). Pubs cashed in on the craze, charging people to listen to plays to kick off boozy afternoons, much the way bars show televised sporting matches today, and hotel lobbies and cafes in Paris also installed the service at coin-operating listening stations. Pretty soon, Britons caught on, with groups of high society ladies and gentlemen gathering in parlors to listen to the most sought-after performances. Queen Victoria had a subscription, as did about 600 other people during the turn of the last century.

Ader saw that the theatrophone was trés cool among the hip and happening of Parisian society and launched the Compagnie du Theatrophone. Not a great deal is known about the company, besides the fact that it closed down in the 1930s—about 50 years after it opened. Why? By the time the 20th century rolled around, radios had improved and become the preferred method of entertainment. They were also much cheaper than paying for a subscription for a theatrophone, which by then wasn’t as reliable as a handheld radio for transmitting information.

So the next time you watch a live feed, just remember: The Parisians were there way before you.