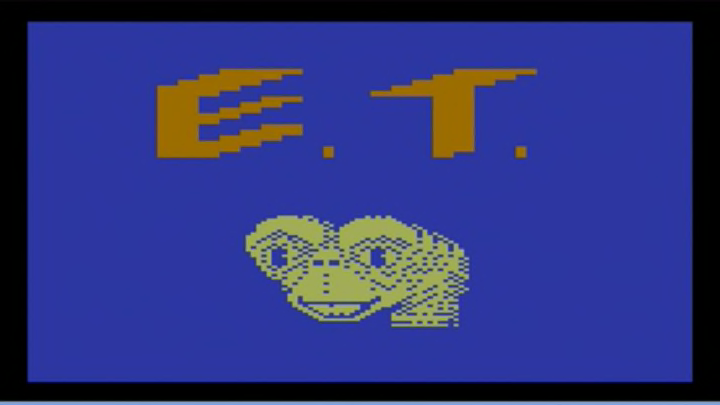

When Atari released their video game adaptation of E.T. The Extraterrestrial in 1982, they thought it would buoy their brand and help them compete with the growing home computer market. Instead, it helped contribute to their demise. For Atari, E.T. became a symbol of failure. For children of the '80s, it was just considered a very bad game. But how did Atari end up creating a video game that was so monumentally and infamously unpopular?

According to the game’s programmer, Howard Scott Warshaw, the game’s failure came down to a mix of too much ambition and too little time. In recent interviews with the BBC and The Guardian, Warshaw explained that he was asked to make the E.T. video game after creating a popular Atari adaptation of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Warshaw, who idolized Stephen Spielberg, enthusiastically agreed to work on the game. There was only one problem: Atari needed it finished in time for Christmas, which meant that Warshaw only had five weeks to make it. At the time, most games took six months.

But rather than play it safe and build off of existing video game formats, Warshaw wanted to make something that was worthy of his hero. “I knew it was a lot to ask. But I didn’t just think, ‘I’ll give it a go.’ If you’re gonna bite it off you might as well take a big bite," he told The Guardian.

Warshaw worked on the game non-stop for weeks, even having a second work station built in his home so he could work at all hours. He managed to complete the game by the deadline, but though the finished game was original, most players didn’t think it was much fun. It was widely considered too difficult and too full of unexpected traps. Its problems weren’t in the game’s code, but in its conceptualization.

E.T. didn’t just disappoint, it bombed—dramatically. In the end, Atari wound up with so many unsold copies of the game, they buried them in the New Mexico desert. And Warshaw, discouraged by the game’s dramatic failure, ended up leaving the video game industry completely. After dabbling in real estate and film, he now works as a therapist in Silicon Valley, where, according to BBC, he advertises himself as “fluent in both English and nerd.”

[h/t BBC]