Plaster casts of dead people's faces were popular for centuries as a means of preserving a beloved or revered individual's features for posterity, before putrefaction rendered them unrecognizable. Some masks went on to have rich lives of their own, either widely reproduced and sold, used to make realistic (and surrealist) posthumous portraits, employed in scientific research, or even transformed into life-saving devices.

1. KING HENRY IV OF FRANCE, DIED 1610

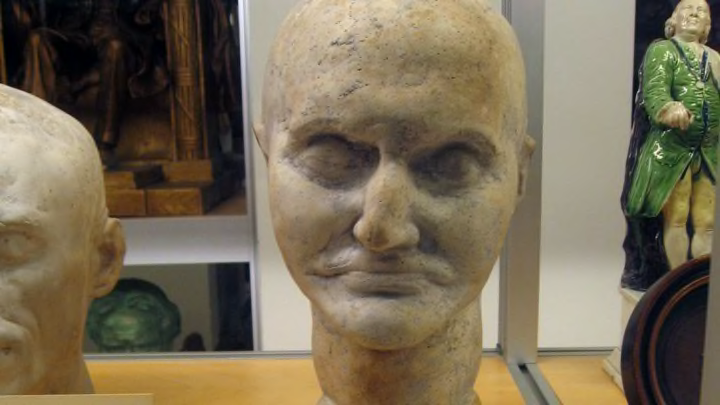

Most death masks are cast as soon as possible, before decay distorts features and makes applying plaster a slippery proposition. Henry IV, on the other hand, had been dead for nearly 200 years when his mask was made.

It was July of 1793 when the National Convention, in anticipation of the first anniversary of the abolition of the monarchy and the creation of the first French Republic, decreed that all the royal tombs be destroyed. The Basilica of Saint-Denis was the prime target; the church was known as the royal necropolis because almost every king of France from Clovis I (465-511) to Louis XV had either been buried there or had his remains reinterred there.

When the tombs were opened, the most ancient remains were ash and bone fragments. Most of the Bourbons, except for the most recent, were putrefied and emitted noxious vapors, a condition that the Revolutionaries saw as the bodily manifestation of the corruption and sin of the Ancien Régime. The body of Henry IV, the first Bourbon king of France, on the other hand, was exceptionally well-preserved. Unlike his successors, he had been embalmed "in the style of the Italians" (i.e. with minimal cutting and no removal of the brain) by his personal physician Pierre Pigray. His head was intact, his features pristine down to the eyelashes, his beard and mustache still soft.

To record this remarkable survival, on October 12, 1793, a plaster cast was made of Henry IV's face. His body was propped up in the choir for people to marvel at for a week, and then it was dismembered, tossed in a mass grave with all the other kings and queens of France, covered with quicklime, and buried until the restored Bourbon monarch Louis XVIII had the paucity of remains exhumed from the trench and reburied in Saint-Denis in 1817.

Henry's miraculous head, though, may have survived. In 2010 a mummified head from a private collection, long reputed to be that of Henry IV, was found to match his features. That was later contested when his y-DNA did not match that of living Bourbon descendants. However, this could also be explained by secret illegitimacy in the Bourbon line over the past 400 years. The death mask may prove pivotal in resolving the controversy: If the head maps to the mask, it will be solid evidence that the head of one of France's greatest kings survived the lime pit.

2. OLIVER CROMWELL, DIED 1658

When Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland, died on September 3, 1658, the trappings of monarchy that he had rejected in life were showered upon him in death. He was given nothing short of a royal funeral, and Thomas Simon, medalist and chief engraver of the Tower Mint, was engaged to take his likeness. Simon used the mold to make a lifelike wax replica of the Lord Protector's face to top a wooden effigy. The effigy was dressed in velvet, gold, and ermine, accessorized with the royal regalia—crown, orb, and scepter—and lain in state in the public hall of Somerset House for two months. At the end of November, he was buried with full honors in Westminster Abbey.

Six plaster casts were made from Thomas Simon's original wax death mask, and copies continued to be made for centuries. Most of the later ones were "Photoshopped" the old-fashioned way: Cromwell's lumps and bumps were minimized or disappeared. That's not something Cromwell would have appreciated. According to a third-hand story relayed in Horace Walpole's 1764 Anecdotes of Painting in England, Cromwell's unflinching self-appraisal was the inspiration for the idiom "warts and all," derived from a conversation he had with artist Peter Lely when sitting for a portrait.

"Mr Lely, I desire you would use all your skill to paint your picture truly like me, and not flatter me at all; but remark all these roughnesses, pimples, warts, and everything as you see me. Otherwise, I never will pay a farthing for it."

Today the presence of Cromwell's prominent bumps under his bottom lip and over his right eye are evidence for the age of one of his death masks. The more warts, the earlier the copy. (Cromwell's head, meanwhile, had a whole other strange journey.)

3. PETER THE GREAT, DIED 1725

After Peter the Great of Russia died on February 8, 1725, his wife and successor Empress Catherine I ordered court sculptor Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrelli to make a death mask and molds of his hands and feet. Rastrelli carefully measured the late emperor's body so that he could create a wood and wax effigy that would be accurate in every detail. The effigy was dressed in Peter's own clothes, picked out and placed on the figure by Catherine and her ladies.

That wax and wood effigy complete with original clothing somehow survived the Bolshevik Revolution and is still at the Hermitage Museum today, the crazy wide-open eyes warning all that Waxen Peter, much like the Dread Pirate Roberts, is here for your soul. A far less unsettling bronze death mask cast from Rastrelli's original shortly after Peter's death is also at the Hermitage.

4. JEAN-PAUL MARAT, DIED 1793

Jean-Paul Marat, doctor, journalist, and radical firebrand of the French Revolution, was plagued with a chronic skin disease so severe that by the end of his life he spent most of his time in a bath, warm towels draped over his painful scabs and lesions. That's where he was when Charlotte Corday gained entry on the pretext of having information about Jacobin enemies. On July 13, 1793, Corday stabbed Marat in the chest, killing him almost instantly.

As the authorities were well-versed in violent death at this point, they called on Marie Tussaud, formerly an artist specializing in wax portraits of the aristocratic and famous, to cast a mask of Marat's face. Marie described the event in her memoirs:

"[T]wo gens d'armes came for me to go to the house of Marat, just after he had been killed by Charlotte Corday, for the purpose of taking a cast of his face. He was still warm, and his bleeding body and the cadaverous aspect of his almost diabolical features presented a picture replete with horror, and I performed my task under the most painful sensations."

She would take the wax figure made from the cast with her to London in 1802, where it was exhibited in her traveling shows along with other stars of the French Revolution whose death masks she had cast, including King Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, and Robespierre. When she created a permanent museum in London in 1835, Marat's figure went on display in the famed Chamber of Horrors, while the heads of other despised revolutionaries whose death masks she claimed to have cast (Robespierre, Hébert, Fouquier-Tinville) were in a room with the heads of her beloved Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. According to Marie, Marat's ugly mug was special because, as she said in her memoirs, he was "the most ferocious monster that the revolution produced."

5. NAPOLEON BONAPARTE, DIED 1821

The circumstances behind the casting of Napoleon Bonaparte's death mask are murky, to put it mildly. The former emperor died on the remote island of St. Helena on May 5, 1821, with French and English doctors attending him. At first the making of a death mask seemed an impossible task—plaster was hard to come by on St. Helena—but on May 7 a mold was cast by English surgeon Francis Burton and/or Napoleon's Corsican doctor Francesco Antommarchi. It did not go smoothly. The mold was taken in at least two sections: the face, and the back of the head, ears, and pate.

Napoleon's attendant Madame Bertrand made off with the face cast, leaving Burton with the back mold, which was less than useful without a face to go with it. He sued her to no avail. She returned to France and started making copies, one of which she gave to Antommarchi. Then he started making copies, and he traveled a lot, so pretty soon there were copies of Napoleon's earless face from New Orleans to London. They sold like hotcakes.

By the 20th century, the image of Napoleon's placid face had become iconic, so much so that surrealist René Magritte painted it sky-blue with fluffy cumulus clouds to symbolize The Future of Statues. Meanwhile, nobody really knows which casts are the closest to the original. Museums are lousy with Napoleon face masks, each claiming to be the earliest. A privately-owned one came up at auction three years ago and sold for $240,000, despite a somewhat dubious backstory.

6. AARON BURR, DIED 1836

Brothers Lorenzo Niles Fowler and Orson Squire Fowler were phrenologists, founders of the American Phrenological Journal, and largely responsible for popularizing phrenology in mid-19th century America. In 1836, when they were just starting out, Lorenzo opened offices in New York, where he performed readings on clients, trained students, and wrote extensively on how people's head measurements and bumps reflected their characters.

Lorenzo Fowler had a particular interest in collecting phrenological busts, which captured in plaster the entire heads of their subjects, and it seems he wasn't entirely scrupulous in how he went about securing casts—Aaron Burr's being a case in point. On September 15, 1836, the day after Aaron Burr died, an associate of Lorenzo Fowler's cast Burr's death mask. He did it phrenology style: covering the whole head and neck in plaster for optimal bump analysis. According to an 1895 article in the New York Times, Fowler had his man stake Burr out in the days before his death:

A mysterious stranger haunted the house for many days and nights before the death of Burr. He never was admitted to the recluse, but always made interested inquiries concerning his health, and he was supposed to be either a relative or an interested friend of the statesman, although he was neither. The man was faithful to the determination, and almost immediately after Aaron Burr's death put in an appearance and, without saying, "By your leave," opened his satchel and proceeded, as if he had a right to do so, to take a plaster cast of the dead man.

Burr's questionably acquired skull cast was soon installed in the Phrenological Cabinet, a museum and publishing house in New York colloquially nicknamed "Golgotha," which over the years grew into an enormous collection of casts made from the skulls of notorious murderers and other assorted cautionary tales, as well as famous celebrities with ideal skull topography. By the early 1850s, it was advertised as "containing busts and casts from the heads of the most distinguished men that ever lived," Aaron Burr among them.

7. WILLIAM TECUMSEH SHERMAN, DIED 1891

William Tecumseh Sherman, General of the Army, scourge of Georgia and the Carolinas, whose scorched earth campaign through the Deep South crippled the Confederacy's war-making ability, died in New York City on Valentine's Day, 1891. Two days later, famed Beaux Arts sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens arrived at Sherman's home to oversee the casting of the death mask. Saint-Gaudens knew Sherman's features well, having modeled a bust of the general in 1888 that took 18 sittings to complete. He brought with him sculptor Daniel Chester French, who three decades later would design the statue of Abraham Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial, and it was French who made Sherman's actual death mask from the plaster cast.

A year after Sherman's death, Augustus Saint-Gaudens began work on the Sherman Monument, a gilded bronze equestrian statue group of the general being led by Victory, which still stands in Manhattan's Grand Army Plaza. He used the hard-won 1888 bust as a reference.

BONUS: L'INCONNUE DE LA SEINE, LATE 19TH CENTURY

Every other death mask in this list was cast from a famous person whose name and face have gone down in history. But L'Inconnue de la Seine (the Unknown of the Seine) doesn't even have a name. It's her face alone that has gone down in history. The story goes that an unknown young woman, purportedly a suicide by drowning, was fished out of the Seine in the late 19th century. Her body was laid out in the viewing room of the Paris Morgue in the hopes she might be identified. (Visiting the morgue to gawk at dead people had been a popular pastime for Parisians since the morgue opened in 1804.)

A pathologist at the morgue was reportedly so taken with her placid beauty and Mona Lisa-like smile that he made a cast of her face, and soon copies of the cast were being sold in stores and gracing the living rooms of bohemians and bourgeois alike. She has inspired writers from Camus to Nabokov, often seen as an ideal beauty, a muse.

The only problem is there's a good chance the story of L'Inconnue is apocryphal. Her smile requires the kind of muscular control seen in life masks, not in death masks, and the features of drowning victims are usually bloated and distorted. The placid visage of a pre-Raphaelite Ophelia is a fantasy. The reality of drowned bodies sitting in a morgue for three days is very different.

Yet, dead or alive, tragic drowned girl or really excellent model, her mask had the most profound impact of them all. L'Inconnue's popularity inspired Norwegian toy manufacturer Asmund Laerdal to use her face as the model for Resusci Anne, the CPR training manikin that hundreds of millions of people have kissed to learn how to save lives.