Our skin is our largest organ, and one of our most defining: It plays a key role both in how others see us and how we see and display ourselves. A new exhibit at Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum, "Our Finest Clothing: A Layered History of Our Skin," offers a selection of medical and cultural objects that encourage visitors to think about skin in new ways. “I decided I wanted to take a broader view of our skin,” Mütter Museum curator Anna Dhody says. “So instead of focusing on the ‘ology’ of our skin and only talking about dermatology and everything that can go wrong with our skin … we discuss the physical structure of skin, the artistic and cultural aspects of skin, and yes, we do discuss dermatology and skin pathologies.” With that in mind, here’s a selection of intriguing (and generally not-for-the-squeamish) objects on display.

1. WAX MOULAGES OF SKIN DISEASES

An arm with smallpox

Photos are one thing, but for 19th-century physicians trying to diagnose medical conditions, 3D wax models were the gold standard. The Mütter’s exhibit includes wax moulages showing skin cancer, smallpox, gangrene, leprosy, hives, and a giant carbuncle on a thorax, among other afflictions. One model also shows an arm with erysipelas, a burning skin infection also known as St. Anthony’s Fire, while several show the horrifying effects of syphilis in its various stages, as it eats away at skin and bone. “It’s really something to see what syphilis can do to a face,” Exhibitions Manager Evi Numen says.

While the moulages might seem like little more than horrifying props now, they’re not only useful to doctors of the past—for medical students and physicians of today, these studies in wax are often the closest they’ll come to seeing antiquated diseases, as well as conditions that are now rarely allowed to progress as far as they have in these models.

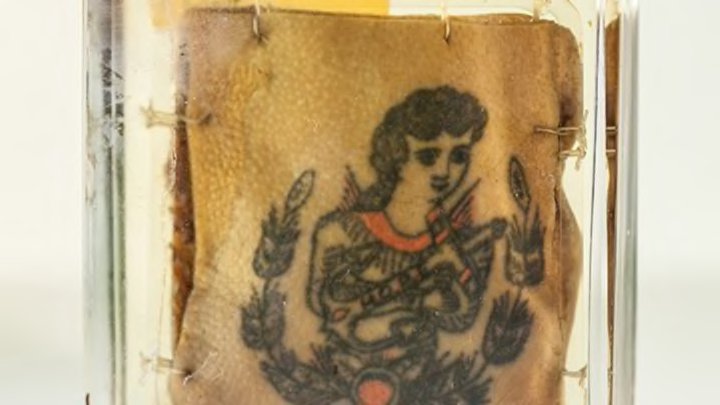

2. PRESERVED EARLY 20TH CENTURY TATTOOS

Watercolor of an arm infected with syphilis after a tattoo.

The exhibit includes several tattoos—and their associated swatches of human flesh—depicting religious and patriotic images, as well as less-expected graphics such as a clown and a tombstone. (Although the exhibit includes five tattoos, the selection on display rotates.) Though their precise origin is unknown, all were originally part of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine’s collection. The vintage ink can be seen alongside information about Otzi the Iceman—the ancient mummified man whose 61 tattoos are the earliest preserved on a human—as well as a watercolor of an arm infected with syphilis after a tattooing session (above).

3. A MODEL OF A WOMAN WITH A HORN.

Madame Dimanch

Of all the reasons to consider yourself lucky, include the fact that you didn’t wake up this morning with a giant horn growing out of your forehead. Madame Dimanch, a 19th-century Parisian widow, wasn’t so fortunate: She suffered from a unique type of growth called a cornu cutaneum, which looks like a horn but is actually an overgrowth of the same keratinous stuff that forms hair and nails. Madame Dimanche had small “horns” all over her body, but by her 80th birthday the one on her forehead had reached an unmanageable 10 inches, and she was convinced to have it removed. The surgery was successful, despite the lack of both anesthetics and antibiotics.

You can see Madame Dimanche’s skull and horn at the Museum Dupuytren in Paris—the object at the Mütter is a wax model, although it’s displayed next to another 20-centimeter-long “horn” removed from a 70-year-old woman. The Dimanche model is one of the original objects collected by Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter, the 19th-century surgeon who founded the museum.

4. A JAR OF SKIN

For some people, this jar alone might be reason to avoid the exhibit after lunch. A few years ago, Dhody received a donation from a woman suffering from dermatillomania (a skin-picking disorder): two Trader Joe’s jars filled with skin the woman had picked from her feet.

“The jar of picked human skin is so interesting because it is the physical manifestation of an impulse control disorder,” Dhody says. “It is hard, sometimes, to show an anatomical/physical example of a mental disorder to the public in a way that engages and stimulates them to learn more about it. This jar of skin grabs people’s attention and they stop and read the label and learn about this disorder and how it affects people’s lives.” The jar on display is actually the second one the woman donated, and it sounds like there’s more to come.

5. ILLUSTRATIONS FROM DERMATOLOGY’S FOUNDATIONAL MODERN TEXT

The exhibit includes several images from English physician Dr. Robert Willan’s On Cutaneous Diseases. While people have been attempting to diagnose and treat skin diseases for millennia, dermatology as a modern field is only about 200 years old. Willan is considered a pioneer in the field, and his book was a landmark text, with a classificatory system and detailed plates that proved highly influential to other physicians on both sides of the Atlantic. It also proves that Willan must have had a pretty strong stomach.

6. SKIN CANCER SLIDES FROM THE MUSEUM DIRECTOR’S NOSE

During a medical screening a few years ago, Mütter Museum Director Robert Hicks discovered he had a common type of skin cancer, a basal cell carcinoma, on his nose. (He blames his years of exposure to the Arizona sun and his fair-skinned complexion.) Hicks successfully underwent Mohs micrographic surgery—in which very thin sections of tissue are removed until no more cancer is found—and the museum now has some microscopic slides from the procedure. Display text alongside the slides notes that Hicks is lucky to be alive now: Before the surgery was introduced during the 20th century, “the cancer might have gradually spread and destroyed much of his face.”

All images provided by the Mütter Museum.