“This dreadful, dark and dismal day Has swept my glories all away, My sun goes down, my days are past, And I must leave this world at last. Oh! Lord, what will become of me? I am condemned you all now see, To heaven or hell my soul must fly All in a moment when I die.”

“The Ballad of Frankie Silver” was supposedly penned in 1833 by a young woman awaiting execution for her husband’s murder. According to some accounts, Silver sang the song as her final statement from the gallows. Today, it’s hard to separate fact from fiction; the lyrics weren’t made widely available until 50 years after the fact, when they were printed in a local newspaper. One hundred and eighty-three years after that, folk singers still perform the sad tale of Frankie Silver, who killed her husband with an axe in 1831.

Frances Stewart was a young teenager when she married Charles Silver, who was just a year older. They settled in a small cabin in Burke County, North Carolina. The story goes that their marriage was troubled from the beginning: Charlie drank, and arguments were common. Frankie gave birth to a daughter they named Nancy, who was 13 months old when Frankie killed Charlie on the night of December 22, 1831. Frankie asked her in-laws the next day if they’d seen Charlie, who she claimed hadn’t returned home from a hunting trip. No one knew where he was. His friend George Young, who he was supposed to have been hunting with, said he hadn’t seen Charlie in weeks. Charlie Silver’s father called the sheriff to investigate.

A search of the young couple’s cabin turned up blood and charred body parts underneath the floorboards. The fireplace held more remains and greasy residue. Charlie’s family buried the pieces of their son as they were found, resulting in three separate plots.

The Silver family was relatively wealthy, while the Stewarts were not. The Silvers assumed Frankie’s family was involved in the killing as part of a scheme to steal the land John Silver had given his son Charlie as a wedding gift. Charlie’s brother Alfred told the story of his brother’s murder as if he had been there, describing how Frankie tried to chop Charlie's head off as he slept. Others accused Frankie’s father Isaiah of helping her murder her husband.

Frankie was arrested, along with her mother and brother, who were suspected of helping her hide the evidence. The charges against her family members were later dropped, but Frankie remained behind bars in Morganton. Her trial began on March 29, 1832, and lasted just two days. Frankie’s lawyer, Thomas Wilson, entered a not guilty plea and maintained that Frankie did not kill Charlie—an act that precluded any opportunity to introduce the concept of self-defense or extenuating circumstances. And the laws of the time didn’t help. Defendants weren’t allowed to testify in criminal cases until the latter half of the 19th century. Witnesses called by the Silver family painted Frankie as a jealous wife who had butchered her husband while he slept. The evidence was circumstantial, and the jury was deadlocked for a time before they asked to rehear some of the testimony. Ultimately, they found her guilty and sentenced her to hang. The State Supreme Court upheld the verdict on appeal, and the date for execution was set for June 28, 1833.

In the year that Frankie Silver waited for her execution date, she finally seized the opportunity to tell her side of the story. She couldn’t read or write, but she dictated letters to her lawyer, asking Governor Montfort Stokes for clemency. Although the letters are lost, it's believed that she explained that Charlie was drunk and abusive throughout their marriage, and that on the night of his death, he was drunkenly attempting to load his gun so he could kill her. Frankie picked up an axe nearby and struck him in self-defense. Her story got out, and over time, public opinion softened on Frankie. Dozens of petitions to pardon her or commute her sentence were sent to the governor, and seven of the jurors signed on. Governor Stokes insisted he could only pardon her if all 12 jurors agreed. A new governor, David L. Swain, was elected in the interim, and while he was sympathetic, he refused to pardon the young woman.

In a last-ditch effort to rescue Frankie, her family helped her escape from jail on May 18, 1833, possibly with the help of the sympathetic jailer. She cut her hair short and disguised herself as a boy. Frankie’s father and her uncle tried to take Frankie to Tennessee, but the police caught up with them as they were headed for the state border.

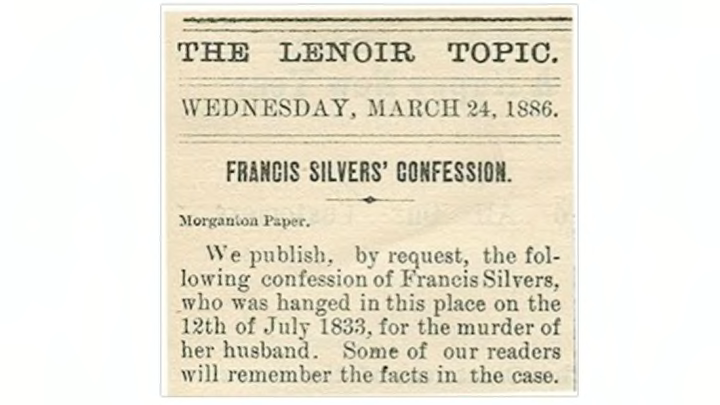

The song some say was Frankie Silver’s “confession” was most likely written by Thomas S. Scott, a Morganton schoolteacher, sometime between Silver’s conviction and execution. The lyrics were supposedly distributed to some of the thousands of people who came to Frankie’s hanging on July 12, 1833. The folklore of the day holds that Frankie asked to sing the song as her last statement, but her father yelled at her to keep silent. Other versions of the tale claim that she actually sang. In reality, Frankie had nothing to do with the song, the lyrics to which you can read here.

Another part of the legend says that Frankie Silver’s father wanted to bury her on family land, but in the July heat, it wasn’t possible to transport her body that far. Silver was buried in an unmarked grave a few miles from Morganton. A gravestone was only added in 1952, paid for by Beatrice Cobb, the publisher of the Morganton News-Herald.

Because Frankie Silver wasn’t allowed to testify at her trial, Charlie’s family controlled the narrative surrounding their son’s death for the next hundred years. Generations of North Carolinian schoolchildren were told the story of the teenage axe murderer, who was said to be the first woman hanged in Burke County (which, though it says so on her headstone, isn’t actually true). In the past few decades, educators and historians have made an effort to tell Silver's real story, lending her the voice she had been denied all those years ago.