"Oh I had to write you telling you that before I started reading these lessons, I was deaf in one ear. I could not hear at all, and after reading the lesson you sent to me, to my surprise on the 17th of December (one week later) my hearing came back to me." —Letter from a Psychiana Devotee, 1944

Frank Robinson was no one’s idea of a prophet. A recovering alcoholic, he had twice been discharged from military service for refusing to dry out. The son of a fire-breathing reverend, his views on organized religion were dispirited. It seemed like all the devout people in his life were hypocrites who lied and cheated.

Robinson rejected concepts of heaven, hell, and salvation that required a person to leave the earth to receive a spiritual reward. He believed everyone, no matter their circumstances, could use the power of affirmation to enjoy life in the moment.

In 1929, he decided to start his own religion from his home in Moscow, Idaho. He called it Psychiana. His initial $2500 investment in advertising and printing would yield hundreds of thousands in profit, close to a million followers, and enough enemies to warrant carrying a gun.

Latah County Historical Society

Robinson claimed he was born in New York City in 1886, although his brother insisted England was his birth place—an important distinction that would eventually land him in federal trouble. His early years were spent in and around Ontario and the U.S., alternating odd jobs with stints in the Royal Mounted Police and the Navy before his alcohol issues would force a change of plans.

In 1919, he married a woman named Pearl and settled into what seemed to be a steady career as a druggist. Robinson had been to Bible Training College but found it unsatisfying. He was a persuasive, bombastic man, but Christian doctrine didn’t sit with him. By the time he was living in Portland in 1925, he had begun to write down thoughts about a religion that preached internal power—what he called the “Now-God.”

In 1928, Robinson convinced his employer at a pharmacy chain to relocate him to a job where his shift ended at 6 p.m. so he could have more time to write and develop his ideas. That request landed him in the tiny city of Moscow, Idaho, with 5000 residents. It very quickly became the headquarters for Psychiana, a name that had come to him in a dream.

Robinson hosted local lectures proselytizing his belief in a spiritually bankrupt world that could be cured by affirmative thinking. Eager to reach a wider audience, he raised $2500 from a co-worker at the pharmacy and local businessmen to start a mail-order operation. He used the funds to print 10,000 form letter responses, 1000 lesson plans, and an advertisement in the nationally-distributed Psychology magazine. The ad claimed he could teach people how to “literally and actually” speak to God.

Latah County Historical Society

According to Robinson’s autobiography, that single ad netted $23,000. With the stock market crash of 1929 devastating the nation’s confidence and the Great Depression settling in, Robinson could have found no better time to promise—with a money-back guarantee—that he held the answers for increased wealth and happiness.

It was certainly working for him. By the end of its first year, Psychiana had sent correspondence to 67 different countries and earned over 36,000 subscribers. By the early 1930s, so much mail was coming in—by some accounts, 60,000 pieces a day—that the Moscow post office was forced to move to a larger facility after being granted first-class status by the postal service. Letters addressed to “Psychiana, USA” still made their way there.

Robinson offered a “course” of 20 lessons that totaled between $20 and $40. Each lesson could be as long as 10 single-spaced pages of Robinson’s self-actualized advice. Letters poured in from people who testified to recovering from health issues or financial loss based on his teachings. Bruno Hauptmann, who had kidnapped Charles Lindbergh’s baby, wrote to say he was a convert not long before going to the electric chair; Italian dictator Benito Mussolini praised Robinson’s movement.

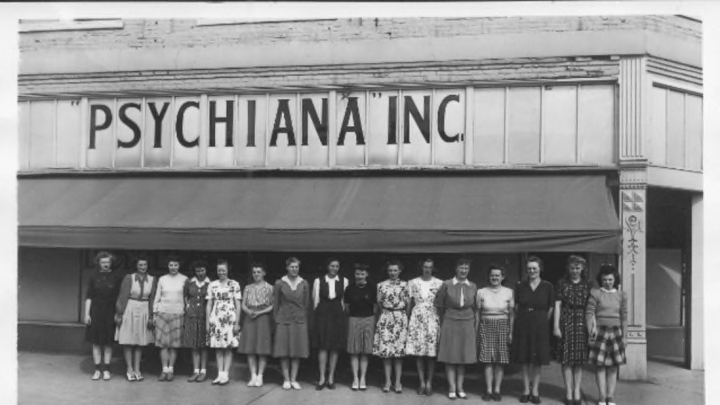

Quitting the pharmacy business, Robinson soon found himself in a lavish fur coat, a custom Duesenberg car, and massive office space that held over 100 employees, making him the largest private employer in Idaho’s Latah County. One devotee, an Alexandria, Egypt-based cotton exporter named Geoffrey Birley, wrote Robinson congratulating him on a breakthrough in self-help. When Robinson looked at Birley’s photo—he requested all correspondence come with one—he told Birley he was the man he had seen in his dream who had urged him to label his movement "Psychiana." An honored Birley sent him $40,000 for the cause.

By 1933, Robinson was so deluged with business that his printing costs totaled $2000 a month. To save money, he decided to buy his own printing press and have it shipped to Moscow. This didn’t sit well with George Lamphere, a local printer and newspaperman who was printing Robinson's mailings and sending him the bill. Lamphere felt threatened by the arrival of a competing printer and warned Robinson that there would be retaliation if his business was affected. In response, Robinson decided to print the city’s second daily newspaper, which only enraged Lamphere further.

Lamphere wasn’t his only rival. Local church groups disavowed Psychiana, calling it a bunk religion and Robinson a “mail-order prophet” in the tradition of P.T. Barnum. Modestly aggressive adversaries would pull flowers out of his front lawn. Robinson began carrying a gun in case anyone felt he should become a martyr. He donated land, built a park, and gave to charities, but response in Moscow was so mixed that he refused to send any of his teachings to correspondents with a local postmark.

Owing to pressure from Lamphere and other groups, the postal service conducted inspections to make sure Robinson’s mail-order business was legitimate. While no red flags were raised, they did make note of Robinson’s passport, which stated he was born in New York. When it came to light he was from England, enemies seized on the chance to proclaim he was an illegal alien who had come into the U.S. from Canada without proper paperwork.

In 1937, Robinson was deported. But just as Lamphere had threatened the power of his political allies, Robinson wasn’t without friends. Senator William Borah intervened on his behalf, allowing Robinson to go to Cuba, get proper immigration papers, and re-enter the country through Florida.

Psychiana had barely missed a beat. As World War II grew heated, Robinson began advertising about the “atomic power” present in both our nuclear weapons and our own spirits. The power of God that resided in all citizens could, he said, defeat the threat of Adolf Hitler.

Latah County Historical Society

With few financial records having survived, it’s difficult to know exactly how much Robinson made from Psychiana. One 1933 balance sheet listed revenue after costs of about $52,000 for the first nine months of 1932, and business seemed steady for roughly two decades. In addition to lessons, Robinson sold his autobiography, individual self-help booklets, and other papers. People believed so fervently in Psychiana that Robinson once declared it the eighth most-popular religion in the world.

It would not, however, outlive him. Following a heart attack, Robinson died in 1948 at the age of 62. Though his son, Alfred, tried to keep the presses going, postage rates and declining interest contributed to Psychiana closing its doors in 1952.

Though Robinson always professed altruistic motives for his work, many believed he was nothing more than an opportunist who used economic strife to feed his own bottom line. While no one will know whether Robinson truly believed his own rhetoric, in 1944 he offered to “train” ordained ministers in Psychiana to help spread the word of his selfless gift. The price: $250 per minister.

Additional Sources: The Strange Autobiography of Frank B. Robinson.