Don’t book that trip to Mars just yet: According to a study recently published in the journal PLOS ONE, a quick trip aboard the space shuttle was enough to cause liver disease in mice.

As space technology races ahead, doctors and scientists scurry along, trying to ensure that our travelers will be safe. We know that returning astronauts often experience dizziness, vision problems, weakened immune systems, and more. Yet somehow the liver—which is kind of an important organ—had been more or less ignored. To physicist and biomedical researcher Karen Johnscher of the University of Colorado, this was a pretty big oversight.

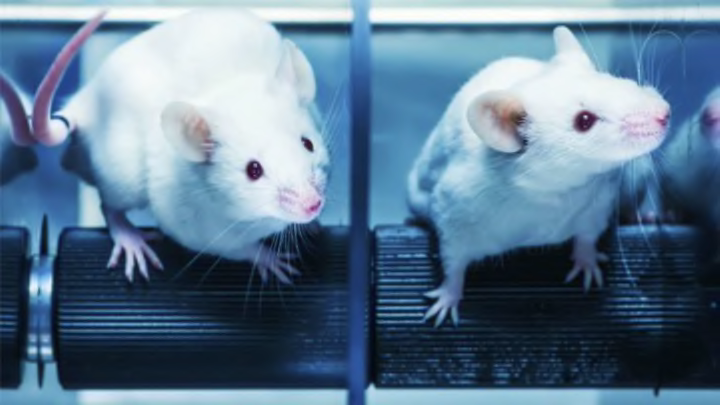

So Jonscher and her colleagues sent 15 female mice into orbit aboard STS-135, the last flight of the Space Shuttle Atlantis. Another 15 stayed on Earth as a control group. The rodents’ voyage was a short one, lasting just 13 and a half days. Once the mice had returned, the researchers euthanized all the mice, weighed them, and took samples of their livers.

These samples underwent a battery of tests, from DNA sequencing and metabolomics (looking at small molecules called metabolites) to chromatography and spectroscopy (to analyze the exact chemical makeup of the tissue samples). Sections of liver were examined under high-powered microscopes.

The differences between the two groups of mice were apparent immediately. All the mice had lost some weight, but those that had gone to space lost nearly twice as much as their counterparts on the ground—even though they’d all eaten the same amount of food. And the weight loss came from different types of tissue. Mice on the ground tended to lose more fat, while the shuttle mice lost lean muscle, which left them with a higher percentage of fat in their bodies. The traveling mice also drank 20 percent less water.

Changes were also evident in the rodents’ livers. Shuttle mice were storing more fat there, they had lower levels of Vitamin A, and the trip appeared to have activated harmful cells called hepatic stellate cells. These cells can lead to inflammation and severe fibrosis, or scarring. The mice appeared to be in the early stages of a condition called non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). And all this in less than two weeks.

"It generally takes a long time, months to years, to induce fibrosis in mice, even when eating an unhealthy diet," Jonscher said in a press statement. "If a mouse is showing nascent signs of fibrosis without a change in diet after 13 ½ days, what is happening to the humans?"

The researchers noted that high levels of stress can trigger hormonal changes and inflammation, and that going up in a space shuttle could certainly cause high levels of stress.

"Whether or not this is a problem is an open question," Jonscher said. "We need to look at mice involved in longer duration space flight to see if there are compensatory mechanisms that come into play that might protect them from serious damage."