William Beaumont didn’t know what to expect when he was called to a fur shop to examine a gunshot victim, but he also knew there was no other alternative. As the only physician present at Fort Mackinac in the Michigan territory in 1822, Beaumont represented the victim's lone chance of survival.

When Beaumont entered the shop and saw a portion of the man’s lungs sticking out from his chest, those chances didn’t look good.

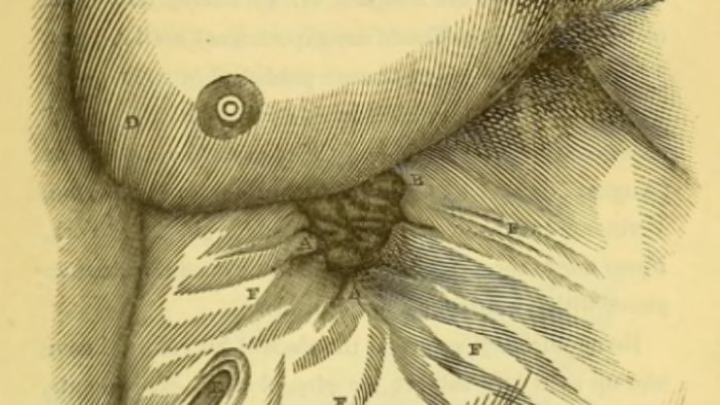

The protruding organ part was “as large as a turkey’s egg,” Beaumont later wrote, and was accompanied by an external portion of the patient’s stomach “with a puncture … large enough to receive my fore-finger.”

Beaumont prodded the man, Alexis St. Martin, considered that any effort to save him would be “useless,” and pondered what to do next. Despite the grim odds, he treated the gunshot wounds, and the doctor wound up with more than just a grateful patient. He had inadvertently struck up a friendship with the man who would offer medicine unprecedented—and literal—insight into the body’s digestive tract. Beaumont could see right into St. Martin’s stomach, watching as it digested the food he lowered into it with a string.

Experiments and Observations via Archive.org

Beaumont had originally been urged to join his family’s farming business in Connecticut. In 1806, at the age of 22, he headed out of state, eventually settling in Vermont to apprentice under a physician. Armed with his medical license, Beaumont enlisted, treating wounded soldiers during the War of 1812. After spending several years in private practice, he reenlisted in 1819 and was dispatched to Fort Mackinac, where he encountered St. Martin for the first time.

His patient-to-be was a 19-year-old French-Canadian (although he might have been older) who made his living transporting fur from Indian traders to storefronts. While at the American Fur Company, St. Martin had been the accidental recipient of a musket shot full of duck load from less than 3 feet away. As Beaumont tended to him, he noticed the force of the projectile had injected bits of clothing into his stomach and lungs. The former leaked portions of St. Martin’s breakfast.

“After cleansing the wound from the charge and … replacing the stomach and lungs as far as practicable,” Beaumont wrote, “I applied the carbonated fermenting poultice and kept the surrounding parts constantly wet.”

The prognosis is poor for most anyone who endures that kind of wound at close range. With the limited scope of medicine in 1822, St. Martin’s chances were slim: he spiked a raging fever. But just a few days later, the young man seemed to be on the rebound—save for the fistula under his right nipple that wouldn’t close. Beaumont kept the wound covered and administered nutrition and hydration through St. Martin’s rectum until the dressing was able to retain his stomach’s contents, an event marked by the arrival of “very hard, black, fetid stool.”

Just over a year and a half later, St. Martin was as healed as he would ever be. His stomach hole, measuring 2.5 inches in circumference, had developed a fine skin of lining that kept contents in but could ooze gastric juices and bits of food if depressed like a valve. Though Beaumont had suggested they try to suture the edges closed, St. Martin refused. Lethargic and depressed, his days as a fur courier appeared over.

Historical via Tumblr

Beaumont sensed opportunity. With St. Martin out of work, he invited the young man to come live with him and perform odd jobs on Beaumont’s property. For the doctor, it meant having a live-in guinea pig for scientific curiosity regarding the stomach, which was still decades away from being visualized by scopes.

St. Martin, whose options were limited, agreed. Beaumont began his studies in 1825, tying bits of beef, bread, and cabbage to a string and lowering it into the fistula. He would then instruct St. Martin to spend a few hours tending to household chores. When he returned, Beaumont would retrieve the food and log the rate of digestion. At one hour, the bread and cabbage was half-digested, the meat untouched. At hour two, the boiled beef was gone, but some salted samples remained.

Other times, Beaumont siphoned out gastric juices to see if they had the same effect outside of the stomach and in a test tube as they did inside: Although most often the test tubes were kept warm in a sand bath, he also occasionally stuffed the tubes into St. Martin's armpit to keep them warm. While it took far longer, the liquid still broke down food, which revised the commonly-held belief that digestion was mostly a mechanical process. Beaumont would also request St. Martin fast, or allow a thermometer to be introduced into the fistula to gauge his stomach temperature—usually a flat 100 degrees.

After several years working for Beaumont, St. Martin left without his consent and returned to Canada. The two didn’t meet again until 1829, when Beaumont hired the American Fur Company to find St. Martin and convince him to return. This time, Beaumont conducted his experiments at Fort Crawford, Wisconsin. Again, the doctor lowered bits of food into the fistula, eyeing it for a response to various foods. When St. Martin grew annoyed at the experiments, Beaumont jotted down that anger had an effect on digestion.

This new arrangement lasted for two years, at which time St. Martin and his family moved back to Canada. In 1832, Beaumont was able to reunite with his singular patient briefly, and took the opportunity to examine how St. Martin’s stomach responded to food and how food responded to stomach acid before the two split for the third and final time.

Experiments and Observations via Archive.org

St. Martin intended to allow Beaumont to continue his studies, but the death of one of St. Martin's children halted any further travel. With enough clinical material collected, Beaumont published a book in 1833 titled Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice and the Physiology of Digestion. For the first time, medicine had an understanding of the role of hydrochloric acid in the stomach, how it differed from mucus, and discovered how the stomach’s motility aided food processing. His contributions were so significant that he was later lauded as the “father of G.I. physiology."

Though St. Martin arguably made the biggest contribution in the partnership, he was not as well-regarded. Prone to excessive drinking, he complained frequently of the discomfort created by the fistula, took demeaning public appearances for money, and was coolly referred to as “old fistulous Alex” by Beaumont.

In 1853, the doctor died after taking a bad fall on ice. Despite his chronic ailment, St. Martin outlived him by 27 years, succumbing to old age in 1880. He had endured roughly 238 of Beaumont's experiments. One of their last meals together was on October 26, 1833, when St. Martin enjoyed fricasseed breast of chicken, liver, gizzard, boiled salmon, boiled potato, and wheat bread. All of it was pre-chewed and stuffed into tea bags. St. Martin's stomach did the rest.