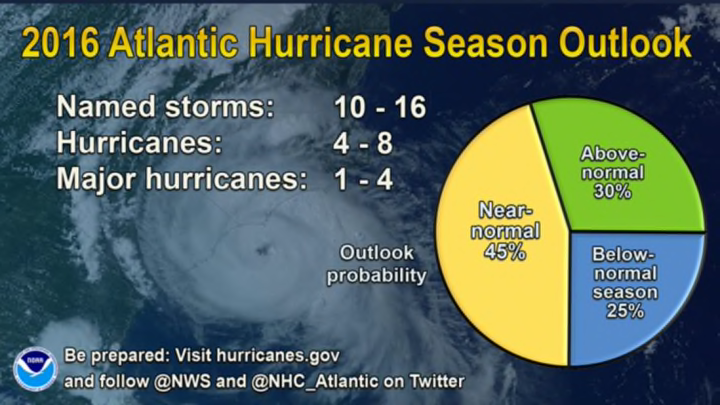

If you live near the Atlantic Ocean or Gulf of Mexico, this isn’t the best year to let your guard down while you enjoy the warm weather. The U.S. National Weather Service (NWS) expects a near-normal Atlantic hurricane season in the months ahead, meaning that we’ll probably see more than a dozen named storms this summer and fall, about half of which could become hurricanes. Moreover, a handful of those hurricanes could be major, reaching category three or stronger on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, which suggests "devastating damage" could occur.

The experts call for 10 to 16 named storms, of which four to eight could reach hurricane strength, and one to four of those hurricanes could wind up a category three or higher, packing winds of 115 mph or more. (An average hurricane season in the Atlantic Ocean would see 12 named storms, six hurricanes, and three major hurricanes.) Last year—with 11 named storms and four hurricanes, two of which were major—was the closest to average we’ve seen since 2012.

This prediction from the United States’ official weather forecasting agency is in line with seasonal predictions issued by other outlets, including those from Colorado State University [PDF] and The Weather Channel, which also call for near-normal activity. The NWS forecast notes that there’s also a not-insignificant chance that this year could come in above average, and there’s only a 25 percent chance that this hurricane season is unusually quiet.

Hurricane season in the Atlantic Ocean officially begins on June 1 and runs through November 30, with the traditional peak occurring around the middle of September. Tropical cyclones can and do form outside of this timeframe; it’s not unusual to see a tropical storm form in late May, for example. A “named storm” is a tropical storm or hurricane that’s assigned a name by the National Hurricane Center. The next name on the Atlantic’s list in 2016 is Bonnie, followed by Colin, Danielle, and Earl.

Hurricane forecasts come with two large caveats. The first is that this year’s numbers include Hurricane Alex, an unusual hurricane that formed in January in the northeastern Atlantic near the Azores Islands, the first hurricane to form so early in the year since 1954.

The second caveat is that long-range hurricane forecasts like the one issued by the NWS aren’t perfect, but they’re a good idea of what we can expect going into hurricane season based on trends we see right now. We can see the big picture that could make storm development more favorable, but each storm requires a precise environment in order to come together. The biggest factor that will drive this year’s hurricane season is the waning El Niño in the eastern Pacific Ocean. The abnormally warm water near the equator can stifle hurricane activity in the Atlantic Ocean by creating wind shear that flows east over the Caribbean and southern Atlantic. Wind shear is the arch nemesis of tropical cyclones; strong winds in the upper levels of the atmosphere shred thunderstorms apart, causing them to die out, which prevents a tropical cyclone from turning into a serious threat.

The opposite of El Niño, La Niña—in which the waters of the eastern Pacific are cooler than normal for many months at a time—is likely going to develop over the next couple of months, and the temperature anomaly in the Pacific Ocean could serve to boost the Atlantic Ocean’s hurricane season by stifling this destructive source of wind shear. Lower wind shear will lead to more chances for thunderstorms to spin up into a tropical depression or worse.

A long-range hurricane forecast makes no implication of landfalls. The United States hasn’t seen a major hurricane (with 115+ mph winds) make landfall on its shores in more than 10 years, and that streak could very well continue this year. Alternatively, we could have a string of landfalls that will make 2016 seem like the worst year in a long time. There is no crystal ball when it comes to attempting to predict months ahead of time how many storms will make landfall—if any. Meteorologists and weather models still struggle with forecasting the track of a storm when it’s already developed and churning across the sea.

In any case, you should always be prepared for hurricanes whether you’re along the coast or hundreds of miles inland. Hurricanes don’t dissipate as soon as they hit land—they can continue moving inland for days and produce flooding rains, strong winds, and tornadoes.