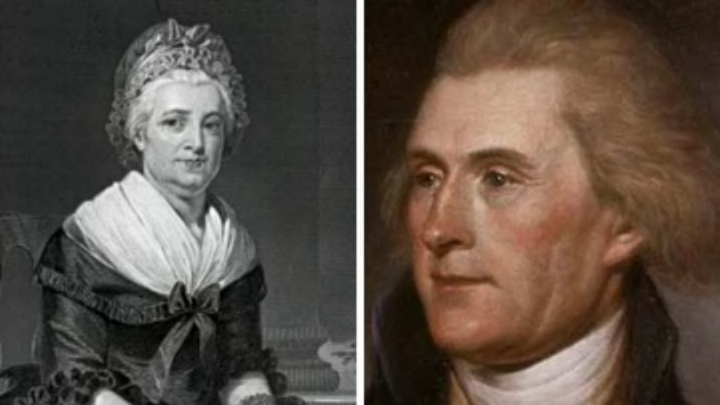

Our founding fathers had as many beefs with one another as today's politicians do. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, for example, would probably be horrified to know that they’re destined to spend eternity stuck side-by-side on a mountain in South Dakota. Though the first and third U.S. presidents were once friends, the relationship soured after the Revolutionary War, especially when some of Jefferson's rather unflattering, thinly veiled comments about Washington were published.

Washington himself was guarded about what he publicly said about Jefferson, but his wife was a little more forthcoming, especially after she became a widow on December 14, 1799. Losing George was the worst thing that had ever happened to her, Martha once said—but hosting Jefferson at Mount Vernon was right up there. According to a friend, Martha called Jefferson's visit the second “most painful occurrence of her life.”

Martha spent time in many of Washington’s camps, including Valley Forge, and saw the horrors of war firsthand. She was also no stranger to personal tragedy: In 1754, her 2-year-old son Daniel died. Three-year-old daughter Frances followed in 1757. Three months after Frances's death, Martha’s first husband died, leaving her widowed with her two remaining young children. Sadly, they also died before Mrs. Washington—Martha “Patsy” Parke Custis was just 17 when she died following a seizure, and 26-year-old Jacky succumbed to “camp fever” while serving at Yorktown in 1781. Despite burying so many of her loved ones, Martha apparently believed that entertaining Jefferson topped them all.

In January 1801, Jefferson, a presidential candidate, decided to visit Mount Vernon to pay his respects to the grieving widow. It probably wasn’t out of the goodness of his heart—Washington had been dead for more than a year, and the trip was highly publicized, likely with the hopes that it would help him win favor with the Federalists.

Though Martha allowed the visit, she remarked to clergyman Manasseh Cutler that she found Jefferson “one of the most detestable of mankind,” and believed that his election was the “greatest misfortune our nation has ever experienced.” It might be a good thing that the former First Lady didn’t have to witness most of the Jefferson presidency: She passed away in 1802, a little over a year into Jefferson’s eight-year reign.