With every decade comes a few products that go from obscurity to gift list must-haves—seemingly overnight. But what happens to the people who turn a novel idea into a household name? Here are eight cases.

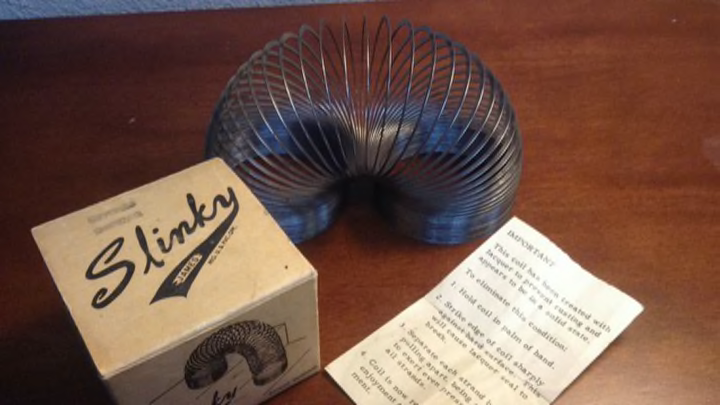

1. RICHARD T. JAMES // THE SLINKY

During World War II, Richard T. James was a naval engineer stationed at a base in Philadelphia. According to legend, he knocked a torsion spring to the floor one day and watched it keep moving, and an idea for a toy was born.

In 1945, James manufactured 400 of what his wife Betty dubbed “the Slinky.” He sold all of them after giving an in-person demonstration at Gimbels department store in Philadelphia during the holiday season. Two years later, Slinkys had become a phenomenon. James moved production to a machine shop in Albany, paid for an advertising campaign, and by 1950 had racked up $1 billion in revenue (in today's dollars).

Then things got weird. The newly wealthy James went through a philandering phase. To repent, he gave away huge amounts of money to evangelical Christian groups, which became sort of an addiction. He continued to donate as the Slinky fell out of fashion and revenue stalled. In 1960, with no forewarning or explanation, he bought a one-way ticket to Bolivia, leaving his wife and six children. Betty James believed he joined a cult in a rural part of the country. She took over the Slinky business and turned it around, thanks in part to plastic and rainbow-colored variations that delighted children of the 1970s. Richard James spent the rest of his life in Bolivia; he died there in 1974.

2. EDWARD CRAVEN WALKER // THE LAVA LAMP

Dean Hochman, Flickr // CC BY 2.0

In 1963, Edward Craven Walker, a British war veteran who ran a travel agency, came across an unusual egg timer in a pub. It was a glass cocktail shaker full of oil and water with a light bulb beneath. A chef could time the boiling of an egg by turning it over and watching the oil globules rise to the top, which also cast moving shadows around the room.

Inspired, Walker spent the next 10 years toiling in his backyard, searching for the perfect combination of oil, wax, and water within a halogen lamp to create what was marketed in the UK as the Astro Lamp and known colloquially in the U.S. as the Lava Lamp. The swirling mass of light and colorful globules beneath the bullet-shaped lamp became the ultimate room accessory for a groovier age. Walker’s company, Crestworth (now Mathmos), sold 7 million lamps a year by the late 1960s.

But Walker’s true passion was being an advocate for the nudist lifestyle and philosophy. Even before the Lava Lamp, he came to some renown producing “naturist” films, such as Eves on Skis (1958) and Traveling Light (1960), which featured nude underwater ballet. He founded the Bournemouth, a nudist spot in the coastal resort town of the same name, and District Outdoor Club, a club in Dorset.

Walker turned the company over to younger entrepreneurs during the Lava Lamp’s nostalgia-inspired revival in the late 1980s. He died in 2000 at the age of 82.

3. CHARLES HALL /// THE WATERBED

For his master’s project, San Francisco State University industrial design student Charles Hall was tasked with creating something to improve human comfort. His first idea was a bean bag filled with gelatin and cornstarch. It weighed 300 pounds and was incredibly impractical.

His second idea was better, and well-timed for the Sexual Revolution. In 1968, Hall developed a “waterbed,” a bedframe filled with heated water. He patented it as “Liquid Support for Human Bodies.” Friends who stopped by his apartment/workshop in Haight-Ashbury dubbed the invention a “pleasure pit.” Hall approached some furniture-makers but was turned down, so he started his own manufacturing company, sold the beds via special order, and delivered them himself around San Francisco. Soon, influential people were buying them, including the Smothers Brothers and members of Jefferson Airplane. Hugh Hefner even had one and covered it in Tasmanian possum fur.

But Hall didn’t become a bedding kingpin, even though, by the mid-1980s, one in every five beds sold in the U.S. was a waterbed. Soon after he started selling to rock stars, cheap knockoffs flooded the market. “We were selling a fairly expensive product when the real volume was in the head shops and counterculture,” Hall said. “It was very much youth oriented, but we weren't selling at youth prices.”

A peaceful man who enjoyed tinkering and the great outdoors, Hall ignored friends’ advice to hire a lawyer to sue the first wave of manufacturers. So none of the furniture companies who joined in the trend thought they owed its creator a dime, partially because the concept had been described before Hall’s patent (famously in Robert A. Heinlein’s classic 1961 sci-fi novel, Stranger in a Strange Land). The cheap beds were leaky and uncomfortable, hastening the end of the fad.

In the 1980s, Hall finally changed his mind and tried to get a cut of the profits made from knockoff waterbeds. In 1991, he won $4.8 million in a patent infringement case against one of the makers of higher-end waterbeds, Intex Plastics of Long Beach.

Meanwhile, Hall moved on to the outdoor recreation equipment market. A company he co-founded, Basic Designs, developed the Sun Shower, a solar-heated portable shower in a bag for campers. He also co-founded Advanced Elements, which develops paddleboards and kayaks, including an inflatable boat that can fit in a car trunk.

And, yes, he still sleeps on a waterbed—in fact there is one in each of the three homes he owns.

4. GARY DAHL /// THE PET ROCK

More than a product, more than a fad, the Pet Rock stands as a practical synonym for a useless idea that makes its creator rich overnight through sheer cultural zeitgeist.

Gary Dahl, an advertising executive, came up with the idea in a bar in Las Gatos, California, listening to his buddies complain about “incontinent dogs, destructive cats, overly fecund gerbils, and vacations foiled because no one could babysit the bird,” in the words of one 2015 obituary for Dahl.

He decided to market a super low-maintenance “pet” as a novelty item. In 1975, he oversaw the production of a series of cardboard pet carrier cases (complete with air holes) that held a single smooth rock, gathered from a Mexican beach, on a bed of straw. It came with a training manual. (A sample: “[P]lace it on some old newspapers. The rock will know what the paper is for and will require no further instruction.”)

According to Paul Niemann's More Invention Mysteries: 52 Little-Known True Stories Behind Well-Known Inventions, newspapers and magazines couldn’t resist the zany story, and Dahl twice appeared on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show. That year, he sold more than a million $3.95 Pet Rocks. He told People, “You might say we’ve packaged a sense of humor.”

The fad fizzled after a few months. Dahl tried for another gag hit: He created a Sand Breeding Kit, with “male” and “female” vials of sand. But soon, he retreated back into advertising, running Gary Dahl Creative Services. But don’t think the man who made a fortune selling rocks was just another stuffed shirt. He opened his own pub in Los Gatos called Carry Nation’s, after the temperance crusader, and won a bad fiction writing contest in 2000. (“The heather-encrusted Headlands, veiled in fog as thick as smoke in a crowded pub …” is how his entry began.)

5. ERNŐ RUBIK /// RUBIK’S CUBE

The Rubik’s Cube was invented by just the kind of person you’d expect: Ernő Rubik was a professor of architecture at the Academy of Applied Arts and Design in Budapest who built geometric models as a hobby. One of these became the prototype for the Rubik’s Cube.

He passed it through Hungary’s patent process, and in 1977 the state trading company, Konsumex, began marketing Rubik’s Cubes. The classic cube consists of 26 small cubes, in rows of three, that rotate on a central axis. When the cube is twisted out of its original arrangement, the goal is to return it to its earlier state, with each colored side in alignment, moving through any number of the 43 quintillion possible configurations. The toy became a global sensation in the 1980s. By the middle of the decade, one fifth of the world’s population had played with one.

In the years following the Rubik’s Cube, Rubik opened a studio dedicated to puzzle games and developed several, including Rubik’s Snake, Rubik’s 360, and Rubik’s Magic. He also dabbled in computer games in the 1990s. Despite splattering his name on products, Rubik himself “shied away from the spotlight for 40 years,” according to a biography attached to a traveling exhibit of his work. In 2009, he was a Hungarian ambassador for the European Union’s Year of Creativity and Innovation events. In a profile for the occasion, he wrote that books were his main passion and that he still has homebody hobbies, naming his favorite pastime as “collecting succulents.”

6. JOHN STALBERGER AND MIKE MARSHALL /// THE HACKY SACK

moises-en-flickr, Flickr // CC BY-SA 2.0

In 1972, 26-year-old Mike Marshall of Oregon City, Oregon, was healing a wounded knee. For his rehab, he used a small sack he’d fill with small objects, such as rice and popcorn, kicking it back and forth to partners. Marshall dubbed the activity “hacking the sack.” His friend John Stalberger, who played baseball recreationally, saw the potential in the game for training the reflexes of athletes.

Kicking around a sack was not new in the 1970s. (In 2597 BCE, Chinese Emperor Hwang Ti had his soldiers kick a leather sack filled with hair to one another as physical training.) But Marshall and Stalberger were the first to apply for a U.S. patent for such an object. They called it Hacky Sack.

According to Josh Chetwynd’s book The Secret History of Balls (yes, that is the actual title), the two tried various fillings (rice, beans, plastic buttons) and skins (leather, pigskin, denim). A few years after Marshall died of a sudden heart attack, Stalberger received a patent. After some success hawking it independently, he sold the concept to the toy company Wham-O in 1983.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the Hacky Sack was unavoidable in college quads, summer camps, and concert tailgates. According to one estimate in Chetwynd’s book, 250 million “foot bags”—both Hacky Sacks and generic competitors—have been sold.

Stalberger went on to live a pretty square life for a guy who popularized an item that’s ubiquitous in the parking lots of Phish concerts. Staying in Oregon City, he founded a construction company and worked as a business consultant and real estate agent while raising a family. He mostly avoided the events for hardcore Hacky Sack competitors, but he reemerged in 2009 to help organize the 29th annual U.S. Open Footbag Freestyle Championships in Vancouver, Washington.

7. DENNIS COLONELLO /// THE ABDOMINIZER

If you had insomnia in the ’80s, the name Dennis Colonello might sound familiar. The Canadian chiropractor made a few cameos in the infomercials for his 1984 invention, a three-foot piece of blue thermoformed plastic with handles called the Abdominizer, which assisted in a curl-like exercise. The infomercials that blared across television screens during the late-night hours invited viewers to “rock, rock, rock [their] way to a firmer stomach!”—promising a tighter tummy for just $19.95, plus shipping and handling.

Colonello invented the device for the farmers he saw at his practice in a small town in Northern Ontario—people who needed to develop core strength without taxing their backs. It went on to sell 6 million units, some of which were used as sleds after users got bored of them.

Although the Abdominizer is no longer manufactured, Colonello rode the invention a long way and is no longer adjusting the vertebrae of dairy farmers. The website for his company, Peak Wellness, claims he “is well known throughout the industry as being the go-to guy for any celebrity in pain or discomfort,” and the practice has offices in the super-tony zip codes of Beverly Hills, California, and Greenwich, Connecticut. He has also worked with the Los Angeles Lakers and Clippers, Dallas Mavericks, Miami Heat, Oakland Raiders, and the Canadian Olympic women’s basketball team.

8. STUART ANDERS /// SLAP BRACELETS

Tim McCune, Flickr // CC BY 2.0

Stuart Anders was fooling around with steel ribbons in his father’s workshop in 1983 when he came up with an invention that would eventually become a staple accessory for teenage girls in the 1990s. About to graduate from the University of Wisconsin-Platteville with a bachelor of science and a certificate in education (if his LinkedIn profile is accurate), Anders went on to stints as an Army helicopter pilot, a high school shop teacher, and a fashion designer, but he never forgot his idea of a bracelet that stands straight until “slapped” against the wearer’s wrist. He even built a prototype.

In 1989, he met toy designer Philip Bart and showed him the bracelet. “I grabbed his hand and slapped it on his wrist,” Anders recalled. “His eyes got really big.” They partnered with Main Street Toys and introduced the “Slap Wrap” at the 1990 Toy Fair.

As soon as the Slap Wrap hit store shelves, countless knockoff bracelets joined it. Anders has estimated that he and his partners sold 6 million bracelets to the 20 or 30 million generic ones sold. And, like Hall’s, the reputation of Anders’ product was sullied by the inexpensive copycats. Kids suffered cuts when the metal ripped through the cheaper fabric, leading parents to become alarmed about the bracelets and school districts to ban them. Between that and a dispute with Main Street Toys that froze him out of royalties for several years, slap bracelets did not provide Anders the financial windfall one would expect for such a popular fad.

During and after the bracelet craze, Anders continued to design swim, beach, and workout wear for a company he owned, Southern Exposure Sportsware. In 1994, he founded Allied Industries, a design and manufacturing firm in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, and is still the head of it.

In 2011, an elementary school in Florida gave students slap bracelets as a fundraising reward and discovered, after doling them out to the kids, the Chinese manufacturer had sent ones featuring drawings of nude women. Anders sent 200 of his brand-name Slap Wraps to the school and an encouraging note telling the kids, “Everyone has the ability to make new things that no one has ever seen before.”