Samuel Augustus Aykroyd, a teacher-turned-dentist who kept a farmhouse near Sydenham, Ontario, liked to host séances. He liked them so much, in fact, that he invited a medium named Walter Ashurst to be his houseguest in 1921. Ashurst didn't leave for 12 years.

Joined by a close-knit group of friends who shared an interest in the paranormal, the Aykroyds held regular attempts to communicate with the dead—an assembly of enjoined hands around a table in the parlor room where Ashurst would appear to pass along messages from beyond. Aykroyd’s 7-year-old grandson, Peter, would watch from a doorway or a staircase as Ashurst's voice took on different inflections, his tongue overtaken by otherworldly entities.

Peter would grow to have children of his own, Peter Jr. and Dan, with tales of Samuel Aykroyd’s academic experiments into the paranormal being passed around the dining room table. Copies of the American Society for Psychical Research journals found their way into Dan’s hands as a teenager. He would later have the idea to write a movie about paranormal investigators who treat the existence of ghosts as a scientific dilemma.

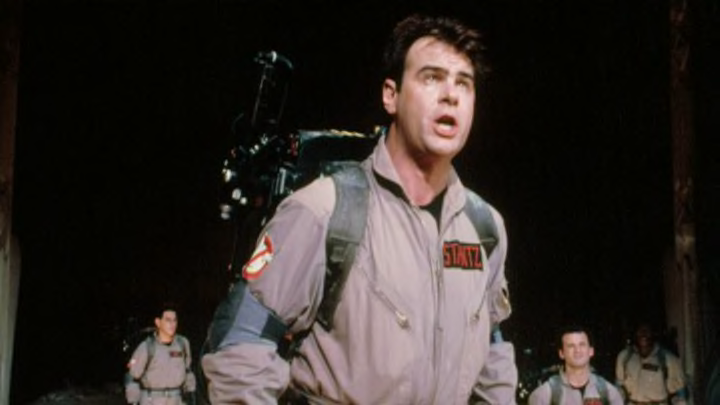

Ghostbusters, which grossed over a quarter-billion dollars in theaters following its release in 1984, was a direct extension of an Aykroyd family tradition: hunting ghosts.

Samuel Aykroyd was born in Ontario in 1855, the oldest of 14 children. It took him until his early thirties to realize his first line of work—teaching—wasn’t for him. He entered dental school and opened a practice in 1894, doing his best to accommodate anxious patients in a time when topical anesthetic consisted mainly of taking a stiff drink.

Though he wasn’t a practitioner, Samuel had come across mention of dentists who had tried using hypnosis to soothe anxiety and promote a relaxed state for treatment. His grandson, Peter Aykroyd—who researched Samuel’s life for a 2009 book, A History of Ghosts: The True Story of Séances, Mediums, Ghosts, and Ghostbusters, believes Samuel soon began to take an interest in the idea that some individuals can be induced into a trance that allows them to act as a conduit between the living and the dead.

He wasn't without company. Samuel met Ashurst, a machine operator, in 1917; the two shared a fascination for spirit communications, and Ashurst told Samuel he believed he could act as a proper medium for the séances Samuel intended to conduct on his farm property in Ontario. By 1921, Ashurst was a medium-in-residence, and Samuel was hosting near-weekly gatherings in an attempt to tune into what he perceived to be the intangible frequency of the afterlife.

According to the journals left by Samuel that detailed his exploration of spiritualism from 1905 to 1933, Ashurst was able to draw the attention of a former member of the Ming Dynasty, a prince of ancient Egypt, and even Samuel’s great-grandfather. In one séance conducted in the home of Samuel’s son, Maurice Aykroyd, a trumpet-like instrument used to correspond with the dead was said to have floated above the heads of the attendees.

Samuel kept notes, and in them he indicated a degree of dissatisfaction with the activities. What he really wanted to do was provoke a materialization, or physical embodiment of a spirit. The séances were held on a schedule and with the same friends in an attempt to make the ethereal more comfortable with showing themselves. Through Ashurst, the spirits would promise they were working on it and ask for patience.

One of Samuel’s bigger preoccupations was with ectoplasm, a seeming manifestation of a ghostly apparition that had been mentioned in spiritual writing but was impossible to document: the gooey material took form only fleetingly, was visible mostly in the dark, and had no physical properties. Again, the spirits suggested the residue of their presence would arrive in short order.

Perhaps the spirits didn’t keep time on a mortal’s schedule. Samuel Aykroyd passed away in 1933, with his séance group slowly dissolving over the next decade. Samuel’s son, Maurice, a Bell Telephone engineer, was convinced spirits might be reachable through a radio frequency device and tried to fabricate one. He was unsuccessful.

These stories and others like them made their way down the Aykroyd family tree, with Maurice’s son, Peter, inheriting his grandfather’s journals and a considerable library of spiritual literature. Peter’s son, Dan, was intrigued by his great-grandfather’s pragmatic approach to such phenomena; deep trances and ectoplasm both make appearances in Ghostbusters, the film he conceived of, then co-wrote with Harold Ramis.

Upon being shown the script, Peter was enthusiastic about the prospect of seeing his family’s roots in paranormal research being honored. Reflecting on the recurring themes in his family tree in 2014, Dan summarized his inherited passion for the paranormal: “It’s the family business, for God’s sake.”

Additional Sources: A History of Ghosts: The True Story of Seances, Mediums, Ghosts, and Ghostbusters