Is Macbeth really Shakespeare’s most cursed play? (Even more cursed than All’s Well That Ends Well?) Perhaps.

Terrible occurrences have dogged performances of Macbeth ever since its premiere, when, according to theatrical legend, either an actor was killed onstage during a sword fight, or else a young boy playing Lady Macbeth died in an accident behind the scenes. (The cause of the curse, some say, is that Shakespeare supposedly included real witches' spells in the play’s script.) But perhaps the darkest incident in the play’s long and murky history occurred on May 10, 1849, when a bitter rivalry between two competing Shakespearean actors sparked a devastating riot in downtown Manhattan.

The two actors in question were England’s William Macready and America’s Edwin Forrest. Both men were at the height of their game at the time, and having twice toured the other’s country, had established names for themselves on both sides of the Atlantic. But while Macready represented the styles and traditions of Great Britain and classical British theater, Forrest—13 years his junior—represented a fresh and exciting new wave of homegrown performers, born and bred in a recently independent America.

Each actor had ultimately amassed an ardent and bitterly opposed following: Macready appealed to wealthy, upper-class Anglophile audiences while Forrest was idolized by the pro-American working classes as a symbol of anti-authority and—barely two generations after the Revolutionary War—anti-British sentiment.

The personal rivalry between Macready and Forrest had originally been friendly and good-natured, and as a popular cause célèbre in the 19th century, press had succeeded in boosting both men’s profiles and their audiences. It had been sparked several years earlier when, on Macready’s second tour of America, he had unwelcome competition.

According to the 1849 account of the riot, rival theater owners of the ones that Macready was set to play decided to book Forrest, who was billed as the “American Tragedian” with the result that Macready’s tour was unsuccessful. Whether deliberate or not, when news broke of Forrest’s ploy back in Britain, it did not go down well with British theatregoers, and during Forrest’s second tour of England the roles were reversed: This time, Forrest’s performances failed to attract large audiences, and were widely savaged by the critics.

Forrest openly blamed Macready for manipulating both the press and the people against him, and accused Macready’s followers of arranging a widespread boycott of his tour among British high society. Seeking revenge, Forrest attended a performance of Hamlet in Edinburgh with Macready in the title role, and loudly jeered and hissed throughout. (Forrest would later claim that he hissed in protest of a “fancy dance” that Macready acted, and said “as to the pitiful charge of professional jealousy preferred against me, I dismiss it with the contempt it merits.”) The feud was officially on.

In early 1849, Macready was on a third tour of America and arranged a performance of Macbeth at New York’s Astor Opera House. The theater was one of the city’s most opulent and a popular hangout for 19th-century New York’s emerging upper classes, but at the premiere performance on March 7, far from attracting a high-society audience, the entire upper tier of the theater had been bought out by a huge number of Forrest’s fanatical working class supporters.

As Macready entered the stage to deliver his first lines, he was resoundingly booed. Jeers of “three groans for the English bulldog!” and “huzza for native talent!” echoed down from the gallery; during the previous scene just minutes earlier, according to reports, the same crowd had wildly cheered the entrance of Macduff—the character who eventually kills Macbeth.

As Macready waited for the commotion to subside, the stage was pelted with eggs, bottles, and rotten fruit and vegetables, and with little alternative, the performance was brought to a humiliatingly premature end.

True to form, across town Forrest was meanwhile staging his own simultaneous rival performance of Macbeth, to a packed house of his own supporters; at the line, “What rhubarb, what senna, or what purgative drug / Would scour these English hence?” his audience erupted into cheers and applause.

For Macready, enough was enough. He vowed to cancel his tour and leave the country for good. Only the coercion of New York’s keenest theatergoers and literary giants (as well as a petition, signed by the likes of Washington Irving and Herman Melville) succeeded in changing his mind, and a second premiere performance was arranged for three days later.

The delay gave the authorities time to prepare: Everyone from the staff at the Astor Opera House (who barricaded the theater’s windows) to the city’s Whig mayor (who, sensing a shortfall in police numbers, arranged for a 350-man militia to be stationed in nearby Washington Square Park) expected more trouble. But not even they could have expected just how bad Macready and Forrest’s feud was to become—just as the authorities had time to prepare, so did Forrest’s increasingly impassioned followers.

Ahead of the May 10 performance, flyers denouncing Macready and his Anglophile supporters—“Shall Americans or English rule this city?” one read—were widely circulated across the city, and by the day of the performance had succeeded in amassing a huge crowd of both disgruntled working class New Yorkers, and newly arrived Irish immigrants, resentful of Great Britain’s failure to act on the famine they had endured back home.

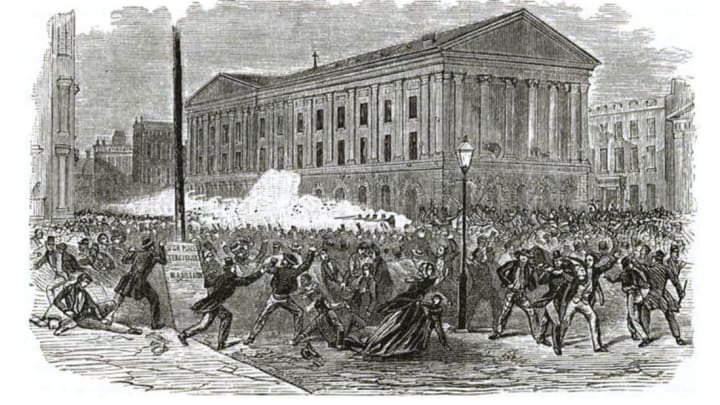

As Macready took to the stage at the Astor on the night of the show, a huge crowd gathered outside, determined to storm the theater, but were beaten back by scores of police. The protest became increasing heated, and as the fighting continued, a company of soldiers joined the fray. But when the rioters began pelting them with rocks and bottles, the militia were given the order to use their rifles. At least 23—but perhaps as many as 31—people were shot dead, several of whom were innocent bystanders.

“As one window after another cracked, the pieces of bricks and paving stones rattled in on the terraces and lobbies, the confusion increased, till the Opera House resembled a fortress besieged by an invading army rather than a place meant for the peaceful amusement of civilized community.” —The New York Tribune

The Astor Place Riot, as it became known, stunned the city. The authorities’ violent response to the situation, and the steady realization of how a seemingly lighthearted rivalry had been allowed to spiral so far out of control, sparked considerable introspection and debate.

In the aftermath, the Astor Opera House suffered financially and eventually closed its doors, later becoming the New York Mercantile Library before being demolished in 1891. Forrest’s reputation, too, was damaged—though not destroyed altogether: he continued to perform (amassing a considerable fortune in the process) ahead of his sudden death in 1872 at the age of just 66. He left much of his great wealth to philanthropic causes, including a home for retired actors he had founded in his native Philadelphia.

Macready, meanwhile, had escaped the Astor by the back door (having reportedly somehow finished the performance) and made it safely back to his hotel. Amid talk that the rioters would seek to track him down there and attack him, he fled the city for Boston, from where he took the first ship back to England. He never returned to America again.