Our lives are shaped by myriad invisible forces, from gravity and magnetism to our own subconscious biases. They’re also shaped, often undetectably, by the thoughts and behaviors of the people around us. For example: Researchers say eyewitnesses shown unfair lineups are more likely to choose the person police want them to choose, even when that person is innocent. The research was published in the journal Psychological Science.

Gone are the days of old-fashioned police lineups, in which a single suspect and a handful of decoys would shuffle into a room and glower straight ahead, left, and right. Today’s witnesses are seated not before one-way mirrors but at computers displaying the mug shots of potential culprits. One of the photos contains the police's prime suspect, who may or may not be the person the eyewitness saw. The other photo subjects are innocent. Will the eyewitness be able to pick the right person? That depends on a few things: their memory, the presence of the culprit in the lineup, and whether or not the police want them to.

Studies have shown that a witness is more likely to select the photo of a person with a distinguishing characteristic if they’re the only one with that feature. Consequently, police can pretty easily and consistently nudge witnesses to pick their bearded prime suspect by including them, beard and all, in an array of beardless decoys. For obvious reasons, this is called an unfair lineup, and it can help send the wrong person to prison.

Researchers at the University of Warwick and the John Jay College of Criminal Justice wanted to take a closer look at the psychology of these unfair lineups. They created four 30-second videos. Each video depicted a white man with some distinguishing feature committing a different crime (carjacking, graffiti, mugging, and theft).

A test audience watched the videos over and over and answered questions about the culprit’s sex, hair color, eye color, weight, and so on. The responses for each culprit were averaged into a single description. Next, the researchers pulled 160 real mug shots matching these descriptions from the Florida Department of Corrections Inmate Database—40 images per culprit. Within the context of this experiment, all of these men were innocent. Their photos would become the decoys, or foils. All of the photos, including those of the culprits, were Photoshopped to show the men wearing plain black t-shirts.

The researchers recruited almost 9000 people online for a study that they said was about personality and perception (psychology studies frequently misdirect participants’ attention in order to get the most natural responses). Each participant was told to watch one of the four crime videos. Afterward, they completed three psychological questionnaires and a word puzzle. The test results themselves were busy work; the researchers just wanted to keep the participants busy for a few minutes to create a break between the ‘crime’ and the lineup.

The participants were asked how confident they were in their ability to pick the culprit out of a lineup. Then the lineup itself began.

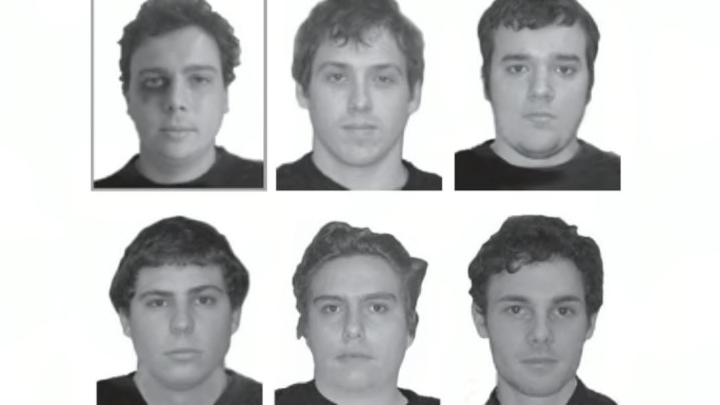

Each participant was shown six photos: the culprit and five foils. Some of the lineups were unfair and included the culprit, complete with a distinguishing mark, and five blank-faced foils. In others, the fair lineups, all six photos had been digitally manipulated to look the same way. Some people saw six men with black eyes or beards. Others saw six photos with pixelated blurs or black boxes covering what would have been a distinguishing feature. (These are all techniques used by real police departments in England and Wales.)

Then there were the people whose lineups were completely culprit-free. Like the culprit groups, some of these all-decoy arrays were unfair, showing five plain photos and one person with distinguishing features. The difference was that all of these men were innocent.

Once in front of the photo array, the participants were told that the culprit might or might not have been present. They then selected the person they believed to be their culprit, or “Not Present” if they felt the criminal’s photo was missing. Finally, they were asked again how confident they felt in their choices.

Unsurprisingly, the authors say, unfair lineups were very effective at getting witnesses to select the desired target. But they were also good at encouraging people to feel good about blaming innocent men; the volunteers shown unfair lineups were more confident than others, even when they were wrong.

University of Warwick researcher Melissa Colloff is lead author on the study. She says an unfair lineup is unfair not only to suspects but also to witnesses. “It could impair their ability to distinguish between guilty and innocent suspects and distort their ability to judge the trustworthiness of their identification decision," she said in a press statement.

“That's because they weren't really using their memory of the culprit's face,” she said. They were remembering the beard, or the scar, or the black eye. If a witness goes to a police station and says they saw a crime perpetrated by a person with a beard, the police may begin to suspect a person with a beard, even if that person is innocent. And if that person becomes a prime suspect and is included in an unfair lineup, the same witness might quite confidently say, “Yes, Officer. That’s him.”

The authors suggest two techniques for correcting the issue. First, they say, police should encourage witnesses to take their time and not answer until they’re sure. Second, of course, they should give witnesses a real chance to identify not just the suspect in a crime, but its culprit.

Know of something you think we should cover? Email us at tips@mentalfloss.com.