In 1871, retired general Augustus J. Pleasanton appeared before the Philadelphia Society for the Promotion of Agriculture and told enterprising Pennsylvania farmers all about how he had used blue glass to develop only the healthiest and most impressive plants and animals. His ideas, published in book form in 1877, kicked off an obsession with the supposed scientific benefits of the color blue that became known as the “Blue-glass craze.”

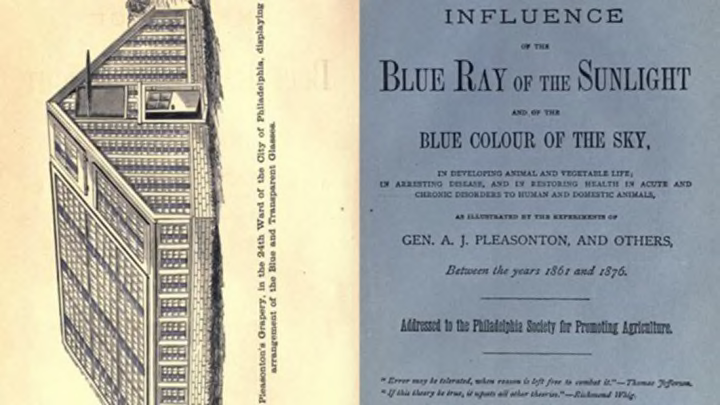

The book’s rambling title shows just how many things Pleasanton thought the color blue could impact, advising readers on “The influence of the blue ray of the sunlight and of the blue color of the sky, in developing animal and vegetable life; in arresting disease and in restoring health in acute and chronic disorders to human and domestic animals.” Pleasanton raised grapes and pigs under the light of blue-colored glass, based on the notion that plants bloom in the spring because of how blue the sky is. He ended up patenting blue-glass greenhouses.

Blue glass began appearing everywhere, not just for agricultural uses, but in people’s houses, in hospitals, in consumer products, and more. One company in Massachusetts was making 3000 square feet of blue glass every day in 1877. But that was also the year that the mania for colored glass began to finally crack. Despite the need for opaque containers to protect chemicals from sunlight, the use of blue glass in vials and bottles of medicine was “persistent” and “irrational,” according to an 1877 reader’s letter to the Druggist’s Circular.

That same year, the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal published in its medical notes a screed against the scientific merits of Pleasanton’s theories, citing a 1712 article that described a similar craze for green lights and fabrics in the 18th century. The journal went on to note that while it had a strict rule against directly prescribing anything to its readers, “we are tempted for once so far to depart from our rule as to suggest to hypochondriacs, who are always on the alert for new remedies, to try the effect of blue pill before investing in blue glass.”

Blue light does have certain scientific properties that influence us, just not in a way that makes pigs bigger and healthier. Short wavelength blue light affects your circadian rhythm, waking your body up—which is why using a computer at night makes it difficult to fall asleep.

Pleasanton’s influence continues today, if not in the ways he might have expected. In 2010, the band OK Go wrote a whole concept album, Of the Blue Colour of the Sky, based on a passage from his book. You can read Pleasanton's whole flawed, trendsetting argument for the color blue for yourself on The Internet Archive.

[h/t Public Domain Review]

Know of something you think we should cover? Email us at tips@mentalfloss.com.