Alfred Carlton Gilbert was told he had 15 minutes to convince the United States government not to cancel Christmas.

For hours, he paced the outer hall, awaiting his turn before the Council of National Defense. With him were the tools of his trade: toy submarines, air rifles, and colorful picture books. As government personnel walked by, Gilbert, bashful about his cache of kid things, tried hiding them behind a leather satchel.

Finally, his name was called. It was 1918, the U.S. was embroiled in World War I, and the Council had made an open issue about their deliberation over whether to halt all production of toys indefinitely, turning factories into ammunition centers and even discouraging giving or receiving gifts that holiday season. Instead of toys, they argued, citizens should be spending money on war bonds. Playthings had become inconsequential.

Frantic toymakers persuaded Gilbert, founder of the A.C. Gilbert Company and creator of the popular Erector construction sets, to speak on their behalf. Toys in hand, he faced his own personal firing squad of military generals, policy advisors, and the Secretary of War.

Gilbert held up an air rifle and began to talk. What he’d say next would determine the fate of the entire toy industry.

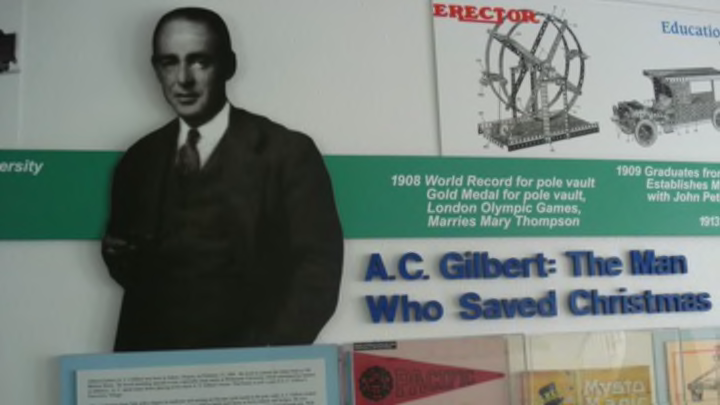

Even if he had never had to testify on behalf of Christmas toys, A.C. Gilbert would still be remembered for living a remarkable life. Born in Oregon in 1884, Gilbert excelled at athletics, once holding the world record for consecutive chin-ups (39) and earning an Olympic gold medal in the pole vault during the 1908 Games. In 1909, he graduated from Yale School of Medicine with designs on remaining in sports as a health advisor.

But medicine wasn’t where Gilbert found his passion. A lifelong performer of magic, he set his sights on opening a business selling illusionist kits. The Mysto Manufacturing Company didn’t last long, but it proved to Gilbert that he had what it took to own and operate a small shingle. In 1916, three years after introducing the Erector sets, he renamed Mysto the A.C. Gilbert Company.

Erector was a big hit in the burgeoning American toy market, which had typically been fueled by imported toys from Germany. Kids could take the steel beams and make scaffolding, bridges, and other small-development projects. With the toy flying off shelves, Gilbert’s factory in New Haven, Connecticut grew so prosperous that he could afford to offer his employees benefits that were uncommon at the time, like maternity leave and partial medical insurance.

Gilbert’s reputation for being fair and level-headed led the growing toy industry to elect him their president for the newly created Toy Manufacturers of America, an assignment he readily accepted. But almost immediately, his position became something other than ceremonial: His peers began to grow concerned about the country’s involvement in the war and the growing belief that toys were a dispensable effort.

President Woodrow Wilson had appointed a Council of National Defense to debate these kinds of matters. The men were so preoccupied with the consequences of the U.S. marching into a European conflict that something as trivial as a pull-string toy or chemistry set seemed almost insulting to contemplate. Several toy companies agreed to convert to munitions factories, as did Gilbert. But when the Council began discussing a blanket prohibition on toymaking and even gift-giving, Gilbert was given an opportunity to defend his industry.

Before Gilbert was allowed into the Council’s chambers, a Naval guard inspected each toy for any sign of sabotage. Satisfied, he allowed Gilbert in. Among the officials sitting opposite him were Secretary of War Newton Baker and Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels.

“The greatest influences in the life of a boy are his toys,” Gilbert said. “Yet through the toys American manufacturers are turning out, he gets both fun and an education. The American boy is a genuine boy and wants genuine toys."

He drew an air rifle, showing the committee members how a child wielding less-than-lethal weapons could make for a better marksman when he was old enough to become a soldier. He insisted construction toys—like the A.C. Gilbert Erector Set—fostered creative thinking. He told the men that toys provided a valuable escape from the horror stories coming out of combat.

Armed with play objects, a boy’s life could be directed toward “construction, not destruction,” Gilbert said.

Gilbert then laid out his toys for the board to examine. Secretary Daniels grew absorbed with a toy submarine, marveling at the detail and asking Gilbert if it could be bought anywhere in the country. Other officials examined children’s books; one began pushing a train around the table.

The word didn’t come immediately, but the expressions on the faces of the officials told the story: Gilbert had won them over. There would be no toy or gift embargo that year.

Naturally, Gilbert still devoted his work floors to the production efforts for both the first and second world wars. By the 1950s, the A.C. Gilbert Company was dominating the toy business with products that demanded kids be engaged and attentive. Notoriously, he issued a U-238 Atomic Energy Lab, which came complete with four types of uranium ore. “Completely safe and harmless!” the box promised. A Geiger counter was included. At $50 each, Gilbert lost money on it, though his decision to produce it would earn him a certain infamy in toy circles.

“It was not suitable for the same age groups as our simpler chemistry and microscope sets, for instance,” he once said, “and you could not manufacture such a thing as a beginner’s atomic energy lab.”

Gilbert’s company reached an astounding $20 million in sales in 1953. By the mid-1960s, just a few years after Gilbert's death in 1961, it was gone, driven out of business by the apathy of new investors. No one, it seemed, had quite the same passion for play as Gilbert, who had spent over half a century providing fun and educational fare that kids were ecstatic to see under their trees.

When news of the Council’s 1918 decision reached the media, The Boston Globe's front page copy summed up Gilbert’s contribution perfectly: “The Man Who Saved Christmas.”