The deepest part of our oceans, the region from below 20,000 feet to the very bottom of the deepest sea trench, is known as the hadal zone. It's named after Hades, the underworld of Greek mythology (and its god). The majority of the hadal zone is made up of plunging trenches formed by shifting tectonic plates. To date, some 46 hadal habitats have been identified—about 41 percent of the total depth range of the entire ocean, and yet less than one quarter of 1 percent of the entire ocean. Scientists still know very little about this mysterious and difficult-to-study region, but what we have learned is astounding.

1. Mount Everest could fit inside the hadal zone’s deepest trench.

The world’s tallest mountain (measured from sea level) would fit inside the deepest sea trench on Earth, the Mariana Trench, with a few miles to spare. This helps explain why it has been so rarely explored—just over 20 people have been to the bottom.

The trenches of the hadal deep are so remote that getting equipment or people to such depths is extremely difficult. This is compounded by the fact that the underwater pressure at that depth—approximately 8 tons per square inch, roughly that of 100 elephants standing on your head—causes ordinary instruments to implode.

Scientists venturing so far down require special equipment that can withstand the immense pressure, but even those can be unreliable. In 2014, the remote unmanned sub Nereus became the latest in a long line of research probes to be lost during a mission. Nereus was built by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and had completed several ground-breaking missions into the hadal zone, including in 2009 when it reached the bottom of the Mariana Trench. But during its last mission, into the Kermadec Trench just off New Zealand, the sub broke apart, likely because of the intense water pressure.

2. The deepest parts of the ocean are measured using TNT.

To measure the very deepest parts of the ocean, scientists use bomb sounding, a technique where TNT is thrown into the trenches and the echo is recorded from a boat, allowing scientists to estimate the depth. While some question the sensitivity of the method, even the rough results are impressive: So far, in addition to the Mariana Trench, four other trenches—the Kermadec, Kuril-Kamchatka, Philippine, and Tonga, all in the Western Pacific Ocean—have been identified as deeper than 10,000 meters (32,808 feet).

3. Jacques Cousteau was the first to photograph the ocean’s hadal zone.

The first expedition to take samples from the hadal zone was the trailblazing HMS Challenger Expedition from 1872 to 1876. Scientists on board managed to extract samples from 26,246 feet beneath the ocean’s surface, but weren’t able to confirm if the samples came from animals that inhabited those depth or those that had died and sunk down to the bottom. It was not until 1948 that a Swedish research vessel, the Albatross, was able to collect samples from 25,000 feet and show that the hadal zone was inhabited.

In 1956, Jacques Cousteau took the first photograph of the hadal zone. Cousteau submerged his camera to the seafloor of the Romanche Trench in the Atlantic Ocean, some 24,500 feet down, providing the first glimpse of this previously unseen part of the ocean.

4. Scientists recently confirmed the deepest sighting of a live fish in the hadal zone.

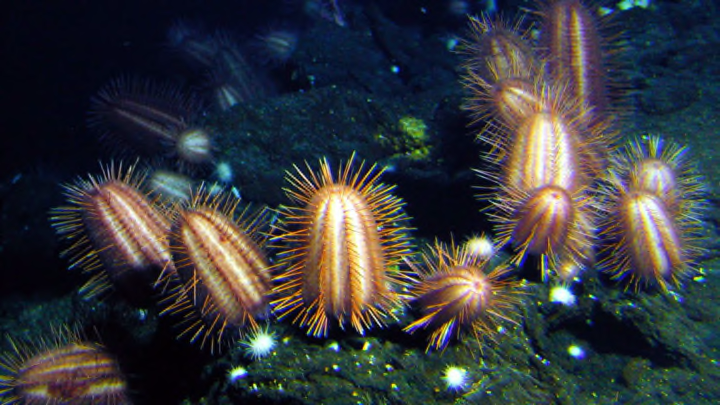

Studying the creatures that survive in the hadal zone can be very challenging. Prior to 2008, most species were described from just one sample, often in a poor state. (One scientist described most hadal samples as “shriveled specimens in museums.”) In 2008, in a huge leap toward understanding deep sea creatures, the first images of live organisms from the hadal zone were recorded. The Japanese research vessel Hakuho-Maru deployed a freefall baited lander in the Japan Trench in the Pacific Ocean, becoming the first scientists to produce images of live hadal creatures there. The camera caught pictures of hadal snailfish (Pseudoliparis amblystomopsis), which are thought to be the most prevalent species at hadal depths. The images surprisingly showed swarms of active fish feeding on tiny shrimp—overturning ideas that fish at this depth would be solitary, sluggish creatures barely eking out an existence. A 2016 paper went on to identify live snailfish at a depth of 26,722 feet—the deepest confirmed sighting of a live specimen.

5. We don’t yet know how much deeper fish might live in the hadal zone.

Recent expeditions such as the HADES project in the Pacific suggest that fish are not found below 27,560 feet. But the hadal zone extends to 36,000 feet. Marine biologist Paul Yancey hypothesized that fish reach a limit around 27,500 feet because proteins at such great depths cannot build properly. To counteract this, deep-sea fish have developed an organic molecule known as trimethylamine oxide, or TMAO (this molecule also gives fish their “fishy” smell), which helps proteins work at high pressure. Shallow water fish have fairly low levels of TMAO, while deep sea fish have increasingly high levels. Yancey proposed that the amount of TMAO required to counteract the huge pressure below 27,560 feet would be so great that water would begin to flow uncontrollably through their bodies, killing the fish.

Below 27,560 feet however, other types of creatures do exist, such as shrimp-like hadal amphipods. These creatures scavenge on the waste and dead bodies from sea creatures which float down from above.

6. Tons of toxic waste was once dumped into one of the deepest parts of the ocean.

In the 1970s, tons of toxic pharmaceutical waste was disposed into the Puerto Rico Trench. Puerto Rico was a large producer of pharmaceuticals, and the dumping was allowed as a temporary measure while a new wastewater treatment site was built. But delays meant that dumping continued at the site into the 1980s. Samples taken from the dump site indicated that ecosystems were seriously damaged by the pollutants, with a 1981 study revealing “demonstrable changes in the marine microbial community in the region used for waste disposal.”

7. Studying the deepest parts of the oceans helps scientists understand how we might survive in space.

Creatures that thrive in extreme environments such as the hadal zone are called extremophiles. These creatures can withstand very low temperatures, high pressures, and little or no oxygen. Studying these extraordinary animals can lend great insights to scientists, indicating how life might persist in space where no oxygen is present. Microorganisms such as Pyrococcus CH1 have been found in deep sea vents, giving scientists an idea of the type of life that could exist on celestial bodies such as Jupiter’s moon Europa.

8. Supergiants live in the deepest parts of the ocean.

Alicella gigantea, a deep-sea amphipod whose common name is “supergiant,” is at least 20 times the size of its shallower-dwelling cousins. This makes them sound huge—but they’re actually miniscule creatures related to the sand hopper, a tiny beast often found popping out of seaweed at the beach at high speed. The largest specimen of supergiant ever found was a 13.4-inch female, found in a trench in the Pacific Ocean.

A version of this story ran in 2017; it has been updated for 2022.