Johnny Brennan and Kamal Ahmed bonded over a dummy. It was the 1970s, and a teenaged Brennan had dressed a human-shaped sack in a football helmet and jersey before launching it off the roof of his parents’ Queens home and in front of oncoming traffic. Panic-stricken, drivers would swerve to avoid a collision while Brennan was in hysterics.

Ahmed, who was several years younger, found that he shared his neighbor’s questionable taste in humor. With Ahmed as a co-conspirator, Brennan would spend much of the 1980s and '90s making prank phone calls to businesses in various character guises, insulting employees or owners with belligerent requests for work. Though it started as a lark, The Jerky Boys would go on to sell millions of albums, star in a movie, and inspire a future generation of comedic talent like director Paul Feig (Bridesmaids) and Seth MacFarlane (Family Guy). Spin magazine once declared them the “Hall & Oates of crank calling.”

There’s just one problem with that comparison: Hall & Oates stayed together.

Although phony phone calls have probably been around for as long as the telephone itself, it wasn’t until the 1960s that entertainers began using them as a premise for comedy. Jerry Lewis made calls using an expensive recording system he had Paramount build for him, releasing the back-and-forth on his albums. Steve Allen did the same, with compilations that came from his late-night talk show.

But it wasn’t until Jim Davidson and John Elmo, better known as the Bum Bar Bastards, decided to prank a salty old bar owner named Louis “Red” Deutsch in the mid-1970s that crank calls morphed into a raw, underground sensation. The two would call Deutsch at the Tube Bar and ask to speak to “Ben Dover” or another sophomoric patron.

Red, who seemed to have a zero-tolerance policy for humor, would escalate the situation rapidly.

“I’ll put a few bullets into you, yo muddaf*ckin’ bum!” he rasped. “Come over here and say these things!” Davidson and Elmo did not, but they did keep calling Red almost every weekend for two years straight.

The “Tube Bar tapes” proved there was an appetite for a garage-band level of prank callers. In 1986, Brennan started breaking up the monotony of his construction job by coming home and pranking New York businesses with a tape recorder running. Honing characters like the brusque Frank Rizzo or the withdrawn Sol Rosenberg, Brennan would rope unsuspecting civilians into his audio sketches, prompting outbursts of anger or resignation; Ahmed would sometimes whisper jokes into his ear.

Ahmed, who worked as a bouncer, gave one of their tapes to a club patron. Before long, the calls were being dubbed and circulated through small-press music ‘zines like Factsheet Five and aired on morning shows. Howard Stern started to recap the machinations of Frank Rizzo.

Calling an auto mechanic, “Rizzo” made his case for an open position.

“Are you applying for a job?” “That’s right, tough guy. I’ve worked on race cars for 18 years … right now I had to leave an old job because of problems with my boss … I’ll come down there with my tools and start work tomorrow!” “I have to hire you first, guy.” “Well, I’m the best!”

Sensing opportunity, Brennan and Ahmed began selling their tapes through a 900 number. Their continued popularity got them signed for a full-fledged record release in 1993.

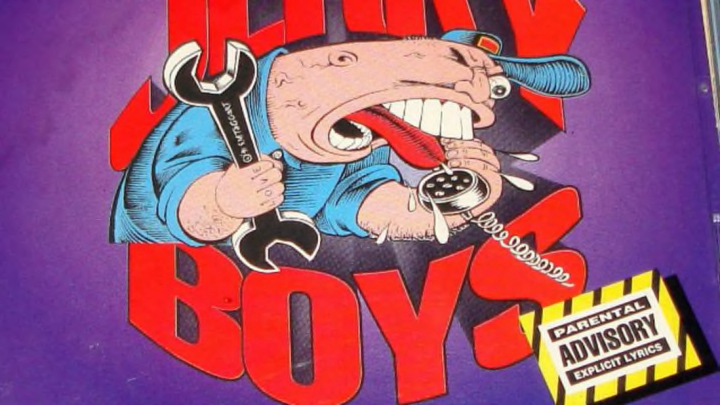

At the time, the team still didn’t have a name. When Brennan told his mother about the album deal, she suggested they call themselves The Jerky Boys.

Bolstered by airtime—and as a consequence, free advertising—on national radio programs, The Jerky Boys went double platinum, selling 500,000 copies. The Jerky Boys 2 followed in 1994, and sold the same number in its first two weeks of release. Brennan and Ahmed quit their day jobs, hired a manager, and devoted themselves full-time to the business of annoying people.

The boys didn’t bother with any legal details early on. Once success hit and the potential for lawsuits loomed, a crank call would typically be followed by a more reserved phone call from their manager, who would try to convince the offended party to sign a release form. Most would: Brennan once recalled that only one suit was ever filed as a result of his years as a telephone harassment specialist.

The success of the albums drew the attention of Hollywood. The kids of singer Tom Jones were reported to be big fans. In 1994, Brennan and Ahmed were courted by actors Tony Danza and Emilio Estevez, who executive produced The Jerky Boys movie in 1995. The film—in which the two played fictionalized versions of themselves—gave them unprecedented visibility but savage reviews. An unimpressed critic from The New York Times noted that:

“As telephone guerrillas puncturing institutional defenses with their rude crank phone calls, the Jerky Boys have touched a nerve. The comic flailings of these self-described ‘lowlifes from Queens’ are comic cries of anger from a social stratum that looks ahead and sees only dead ends. Adopting funny voices and taping phone calls that make fools of their frequently snippy recipients is as efficient a way as any of momentarily leveling the social landscape.”

Undeterred, the Boys released several more albums before Ahmed decided to call it quits to pursue a filmmaking career. The split seemed less than amicable, with Ahmed chastising Brennan for continuing what he felt was a juvenile pursuit and Brennan downplaying Ahmed’s contributions.

Brennan released two more albums in 2001 and 2007, but stayed largely silent. He told Rolling Stone in 2014 that the death of his father in 2000 diluted his passion for pranking: His dad had been an inspiration for the rough-hewn Frank Rizzo character.

While Brennan wasn’t producing much new material, his library of classics endured. Seth MacFarlane, creator of Family Guy, credited Brennan with helping to shape his sense of humor; so did Freaks and Geeks creator Paul Feig, who felt inspired to commit to what people might consider “lowbrow” comedy in films like Bridesmaids.

Today, the 53-year-old Brennan operates The Jerky Boys's official website, which is home to sporadic new calls and a small line of gourmet foods. Although Ahmed is still absent, his business is still plural: Brennan has explained that the “Boys” of the name refers to his characters, not themselves.