Archaeologists at the University of Hawaii West Oahu have begun unearthing a long-forgotten relic from a dark period of American history.

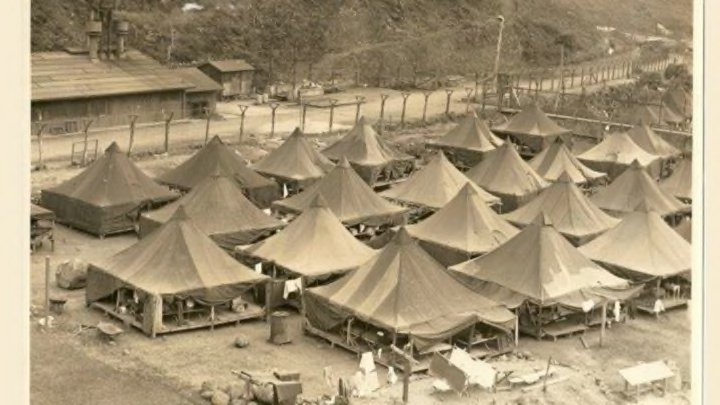

The Honouliuli internment and POW camp was open for three years. In that time it saw the detention of more than 1000 Japanese-American citizens and thousands of prisoners of war.

UH archaeologist William Belcher is leading the excavations. He says that after the camp was bulldozed in 1946, it seemed to vanish from public consciousness. “When I was in elementary school, I never even heard that this had occurred,” he told NBC News. “We never studied this in history or talked about it.”

Thanks in part to former President Obama, that’s beginning to change. Obama, who was born and raised in Hawaii, designated the camp a national monument in 2015. Now Belcher and his students are digging in to help clear the site of seven decades’ worth of earth, grass, shrubs, and debris.

It’s a difficult task made even harder by the landscape. The camp is hidden inside a steep gulch that Japanese-American internees called "Jigoku Dani," or "Hell Valley." It’s unreachable by public roads and gets very, very hot during the day. Belcher and his students are clearing the site with machetes. "The basic technology is to walk in a systematic fashion across the entire landscape," he told NBC News.

The internment situation during World War II looked different in Hawaii than it did in California or Washington state. Forty percent of Hawaiian citizens were of Japanese ancestry, and many of them were plantation workers. To protect the islands’ plantation economy, the government decided to confine some, but not all, citizens within the camp’s crowded enclosures and barbed-wire fences.

In naming the site a national monument, Senator Mazie Hirono told NBC News she hoped that recognizing our country’s troubled history might prevent us from committing similar atrocities in the future.

"The stories of those detained at Honouliuli and internment sites like it across the country are sobering reminders of how even leaders of the greatest nation on Earth can succumb to fear and mistrust and perpetuate great injustice," Hirono said.