Giuseppe Dosi has gone down in history as one of Italy's greatest detectives, a master of disguise who went undercover to solve the thorniest of crimes. Famous in Italian police circles for his pioneering efforts, Dosi has been getting wider attention recently thanks to the publication of a biography, the airing of a new documentary about him, and the digitization of some his papers, now in the Museum of the Liberation of Rome.

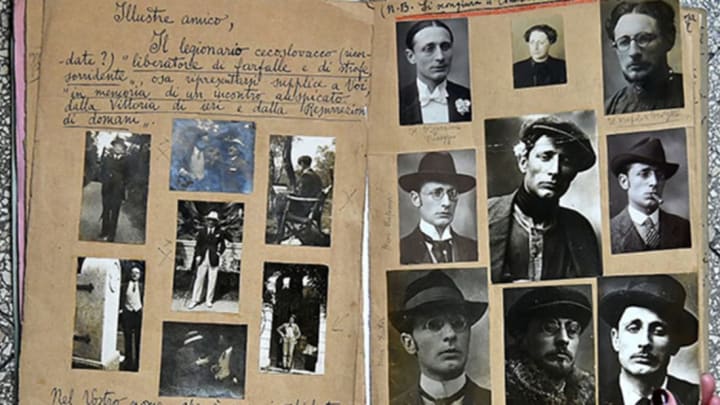

Born in 1891, Dosi’s first love was for the theater. He acted for two years and worked briefly behind the scenes, but he failed to make his career on the stage a success. Instead, he poured his love of performance into his job as a detective. His enthusiastic embrace of disguises became known as fregolismo detectivistico ("detectival transformism”) after the late 19th/early 20th century stage actor and quick-change artist Leopoldo Fregoli. Dosi himself had at least 17 confirmed disguises, including a femme fatale, two priests (one foreign, one Italian), a Galician banker, a German doctor, a Yugoslavian merchant, a nihilist, and a Czech World War I veteran with a bum leg. Five of them were fully fleshed-out identities complete with fake identity documents, background stories, and even their own penmanship.

Dosi’s impersonation of a Czech veteran completely fooled poet and would-be dictator Gabriele D'Annunzio, who in August of 1922 had mysteriously “fallen” out of a window and cracked his skull. Dosi went undercover to find out what had really happened—a politically sensitive investigation since D'Annunzio's greatest rival was one Benito Mussolini, who two months later would march on Rome with his Blackshirts and secure an appointment as the new Prime Minister of Italy.

Dosi discovered that D'Annunzio had been pushed, not by a political assassin, but by his volatile mistress. The case was quietly closed. D'Annunzio, who had dubbed his limping Czech guest the “liberator of butterflies and smiling rhymes” while unknowingly being investigated, called Dosi a "dirty cop" when he found out he was really a nimble Roman.

Actually, Dosi was the opposite of a dirty cop as we mean the phrase today. He was a man of resolute integrity, fearless in pursuit of the truth even when his bosses would have preferred he look the other way—and he paid a high price for it. In 1927, he took on a case that had bedeviled Rome for the previous three years. It was a horrific series of crimes, the rape of seven little girls and the murder of five of them, the youngest just three years old. The atrocities had been breathlessly reported in the national and local press, and the city was in turmoil. Mussolini saw the failure to solve the crimes as a major embarrassment because it made it seem like his law-and-order party could not deliver on its promises. He pressured Chief of Police Arturo Bocchini to arrest someone, and quickly.

So the police found someone. Sure, photographer Gino Girolimoni didn't match the description of a tall, middle-aged man with a bristling mustache and an imperfect command of the Italian language—he was average height, in his 30s, clean-shaven and Roman-born and raised—but he was a warm body, and between riled up public opinion and Mussolini breathing down their necks, that was enough for the police. They ginned up some blatantly fake evidence and arrested Girolimoni in 1927.

Dosi knew the evidence against Girolimoni was flimsy, and was convinced the real murderer was still out there. He reopened the case over the objections of his superiors, and quickly zeroed in on a more likely suspect: a British Anglican priest named Ralph Lyonel Brydges who had been caught in the act molesting a girl in Canada before decamping to Rome. In April of 1928, Dosi got a search warrant for Brydges’s room and found a note in a diary referencing the location of one of the murders, newspaper clippings about the crimes, and handkerchiefs identical to the ones used to strangle the little girls. Brydges had friends in high places, however, and diplomatic interference from Britain and Canada (his wife was the daughter of a very prominent Toronto politician) kept him out of jail. He was briefly committed for observation to the insane asylum Santa Maria della Pietà, only to be released and flee the country.

With the case against Girolimoni in shambles, the police quietly dropped the charges against him. But every newspaper in the country had splashed his name and face on their front pages as the "Monster of Rome" when he was arrested, while his release was covered only in cursory articles in the middle sections of just a few papers. He could no longer make a decent living because everyone thought he was a child rapist and murderer. He died in 1961, penniless and alone. Only a handful of friends showed up to his funeral. Dosi was one of them.

But when Dosi cleared Girolimoni's name, the authorities no longer had their patsy, and the only other suspect was far out of reach. Mussolini, who several years earlier had praised Dosi and recommended him for a promotion after the detective foiled an assassination plot against him, was deeply displeased by Dosi's dogged persistence. (A memoir Dosi wrote in the 1930s, which was critical of his superiors, didn’t help matters.) Dosi's police bosses, already antsy about him exposing their corruption and lies in setting up poor Girolimoni, again felt the pressure from the top to curb their man's hubris.

First they fired him. Then they just cut to the chase and arrested him. He was imprisoned in 1939 in Regina Coeli, a truly scary jail in Rome that during the Fascist period was packed with political prisoners. Apparently that wasn’t severe enough, because they moved him to Santa Maria della Pietà, where the police detective spent 17 months forcibly detained in the same psychiatric facility where Brydges—a certain child molester and possible serial child murderer—had spent only a few nights. Dosi was finally released in January 1941.

Before the end of the war, Dosi’s great courage and initiative would perform another historic service. On June 4, 1944, Allied troops under General Mark Clark liberated Rome. The Nazi occupiers beat a hasty retreat. A mob assembled at the notorious SS torture prison on Via Tasso to free the political prisoners and Jews who hadn't been murdered by the retreating Nazis. On the way out the door, the SS had set their papers on fire in the attempt to cover their tracks, and when the mob freed the prisoners, they tossed bunches of records out the window in a sort of riot of de-Nazifying the place.

Dosi, who lived on a neighboring street, showed up with a cart and took it upon himself to enter the burning building and save all the surviving records. He turned them over to the Allied Command, who appointed him a special investigator for two years. His testimony and the records he single-handedly saved from the flames, including the list of 75 Jews taken from Regina Coeli to their deaths in the monstrous Ardeatine massacre, would be crucial in the prosecution of numerous Nazi war criminals. In November of 1946, he rejoined the Italian police force as director of the Central Office of International Police.

Over the course of his long and storied career, Dosi applied his great energy and dedication to areas of police work that are now standard but were then considered newfangled. He wrote essays on scientific policing, was a vocal advocate for women police officers, promoted photographing and fingerprinting arrestees, and encouraged the preservation of cultural patrimony as well as cross-border law enforcement. He retired in 1956 with the title of Chief Inspector General. He also wrote several books about his detective work and lived a long life, dying in 1981 at the age of 90. He lived as he worked, pouring his tenacity, discernment, endless intellectual curiosity, and vision into everything he did. As he wrote [PDF in Italian ] in an article on police work in 1929:

In a sense, each of us is a born cop, for our own inherited psychophysiological constitution has at its disposal infinite new sources of knowledge. The difficult part can be to evaluate them precisely, to find them, link them, associate them, integrate them, to be able in the end to repeat in triumph the motto that a medieval sage wore engraved on an amulet: "Nil occultum quod non scietur." That is, we may not know something, but there is nothing truly hidden; with hard work, everything can be known.