Picture this: A mosquito lands on your best friend's arm, plunges its needle-like proboscis into the skin, and begins to suck. After a while, the sated pest flies away, and a little red welt inflates in its place. If merely imagining this scenario makes you feel irritatingly itchy, take heart: Scientists may have some idea why. They published a report today on their findings in Science.

Being a social animal means being exposed to all kinds of contagious entities, from germs to yawns. Scientists are clear on how microbes are transmitted from one organism to another, but the the spread of sensations like feeling itchy has proven harder to explain.

But if anybody’s going to figure it out, our money’s on the researchers at Washington University in St. Louis’s Center for the Study of the Itch. (Yep. That’s a real thing.) They set up a series of experiments to find out, first, if mice experience contagious itch too; and second, what that experience looks like in their brains.

The researchers set up pairs of mice in side-by-side cages. One mouse in each duo was chronically itchy—and therefore perpetually scratching—while the other was doing just fine. Sure enough, a single glance at their itchy counterparts was enough to get healthy mice scratching up a storm.

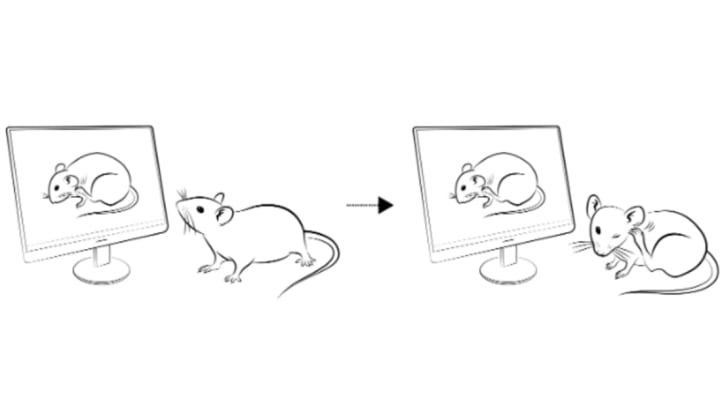

To eliminate the possibility that the healthy mice might be triggered by smell or sound to scratch, the scientists next plopped healthy mice down in cages beside a video screen. The movie? A short clip of an itchy mouse scratching. Sure enough, the mere sight of a fellow mouse, even one in two dimensions, triggered itchy feelings in the observer mice.

Next, they looked inside the rodents’ brains for signs of the contagion. And they found it: Newly itchy mice showed higher levels of a molecule called gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP), especially in a brain region called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), located in the hypothalamus.

The scientists then confirmed that GRP and contagious itch were linked by simply shutting GRP expression off in some rodents’ brains. Even when the mouse beside them scratched, mice with muted GRP did not contract the itch. The researchers turned GRP back on and, voila: itchy, scratchy.

Inevitable caveat: A mouse brain is not a human brain, and more research is needed to validate these findings in other animals. Still, the authors feel they’re on to something that could go beyond an uncontrollable itch. They write, “It will also be of interest to determine whether SCN subcircuits may mediate other types of socially contagious behaviors, such as yawning or empathy for pain.”