An escape from England, an indentured servant with a mysterious past, and an untimely death while crossing the Atlantic. While these might sound like plot points for the latest historical spy thriller, they’re actually real events related to The Bay Psalm Book, a Puritan hymnal—the first book printed in what would become the United States.

LEAVING ENGLAND FOR AN UNCERTAIN NEW WORLD

Reverend Jose Glover was approaching his 40th birthday, and he was in a rut. For several years, he had been Rector of Sutton, and he found himself increasingly drawn to the Puritans, a group that believed the Church of England, which had broken from the Catholic Church in 1534, was still too Catholic. So in 1634, a year after King Charles I had ordered clergymen to read the Book of Sports (which largely served as an anti-Puritan text detailing acceptable Sunday activities) to their congregations, Glover was, along with dozens of others, suspended for refusing to read it [PDF]. Not long after, he resigned and was out of a job altogether.

He decided that the Massachusetts Bay Colony was the change he was looking for. Settled just a few years earlier, it was a haven for Puritans escaping persecution from the more establishment elements within the Church of England. Although it was risky to leave his life and livelihood behind for an uncertain future, the New World offered religious freedom and a fresh start.

To finance his move across the Atlantic, Glover gave sermons and raised cash from both parishioners and friends in England and Holland. With the funds, he bought a press, type, paper, ink, and other supplies he would need to start a printing press in Massachusetts Bay. (Why he chose printing as his new profession is unknown.) Before leaving for New England, Glover also hired Stephen Daye, an indentured locksmith in his forties, to come with him.

Like many parts of this story, why Glover hired a locksmith to help him establish a printing press is a mystery, and not enough is known of Daye's past to make things any clearer. Some historians have speculated that Daye was a descendent of renowned Protestant printer John Daye and worked as an apprentice in a London printing shop. Other scholars, though, argue that there’s no evidence that Daye was related to the famous printer or that he was ever a printer’s apprentice. It’s even possible that Daye was hired exclusively as a locksmith, and was forced into the printing business by what happened next.

In 1638, Glover set sail for Massachusetts Bay on a ship called the John of London, traveling with his wife, Elizabeth Harris Glover, their children, Daye and his family, a few servants, and the printing press. But Glover never made it: En route, he caught a bad fever and died.

His plans to set up a printing press didn’t perish with him, though. After the John of London arrived in Massachusetts in the late summer of 1638, Elizabeth fulfilled her late husband’s wishes, establishing a print shop in a house on what is today Cambridge’s Holyoke Street, near the college that later became Harvard University. It would become known as the Cambridge Press.

The business partners were an odd pair: Daye was a barely literate locksmith, Elizabeth a widow with no business experience. We know that Daye’s teenaged son, Matthew, worked at the press, but it’s unclear how they ran the press or how they split their duties—some scholars credit Stephen Daye as America’s first publisher, while others call Elizabeth the “Mother of the American Press”—but run it they did. For their first job, they printed “The Freeman’s Oath,” a large sheet of paper with Massachusetts Bay’s citizenship oath, in early 1639. They then printed a pamphlet that was an abridged, primitive version of an almanac.

After that, they tackled The Bay Psalm Book.

MAKING AMERICA'S FIRST BOOK

In 1620, the Pilgrims who sailed on the Mayflower most likely brought Bibles with them, but there's no definitive evidence about which versions (or how many) they actually brought. By the 1630s, most colonists in the Massachusetts Bay Colony were worshipping with various hymnals they had brought from England, including a 1562 edition of The Whole Book of Psalms. Dozens of members of the Massachusetts clergy, including John Eliot and Richard Mather, wanted a hymnal that more accurately conveyed the true, literal word of God. In the clergy’s view, the 1562 psalm book was outdated and poorly translated from the original Hebrew.

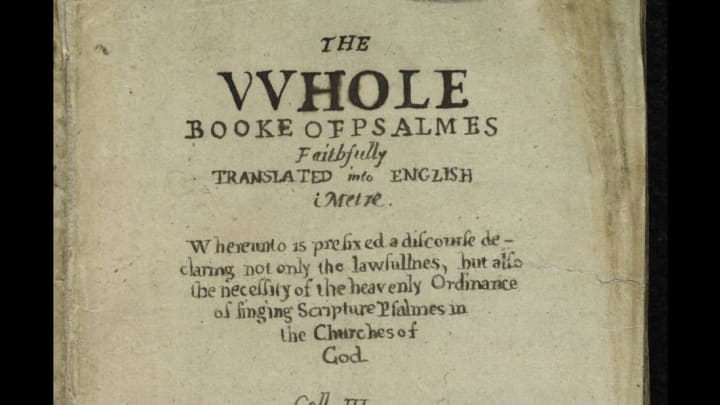

To feel closer to God in their strange new land, Eliot and Mather wanted a new book that didn’t remind them of the religious constraints they faced in England. So in 1636, they began translating Hebrew psalms into English, creating The Whole Booke of Psalmes Faithfully Translated into English Metre, colloquially called The Bay Psalm Book. When it came time to print the tome, they turned to the only press in town: Elizabeth and Daye's.

Elizabeth spent £33 (approximately $7000 today) to publish the book, a simple arrangement of 37 sheets bound with calf-skin. The book (which you can read here) was rife with spelling and spacing errors, due to technological limitations and Elizabeth and Daye’s lack of typographical training. Still, despite its awkwardness, it was a smash hit. The Cambridge Press sold all 1700 first edition copies of The Bay Psalm Book, and Puritan congregations used the book to worship God and teach children to memorize the psalms. The book was sold at the Cambridge Press’s office and at Hezekiah Usher’s bookstore in Cambridge, the first bookstore in New England.

After publishing The Bay Psalm Book, Elizabeth and Daye published a 1641 almanac, a catechism prayer, and a set of Massachusetts laws. But after Elizabeth’s death in 1643 and Daye’s retirement in late 1646, one of Daye’s sons took over the press, and it was most likely dismantled in the mid-1700s.

Today, just 11 first editions of The Bay Psalm Book survive, and they have broken sales records at auctions. Thanks to Elizabeth and Daye’s work, The Bay Psalm Book helped New World settlers feel close to God during a time of uncertainty and helped usher in a uniquely American identity and literary tradition, distinct from England. Not bad for a tiny book published by a widow and an indentured servant.