The first 100 days of an American presidency are some of the most obsessed-over moments of governance: Every activity is tallied, every bill is scrutinized, every press conference is analyzed, and every photo mined for details. Nothing happens in the first 100 days that isn’t dissected at length by a cable news panel.

So where did this arbitrary presidential metric come from, anyway? Why do we care about these early days of an administration more than the other similar blocks of time? To find out, we have to go back to 1933.

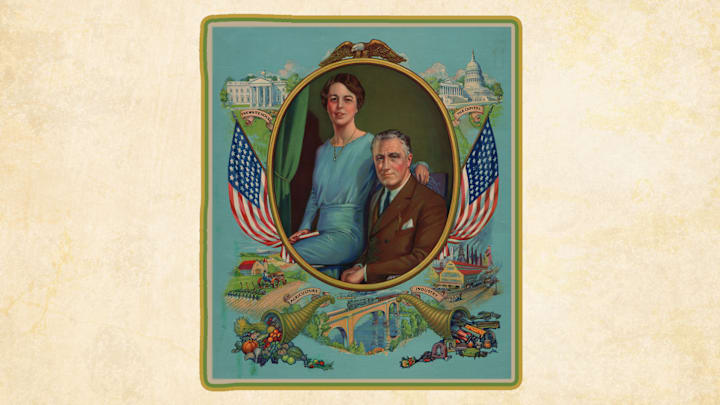

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s First 100 Days in Office

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4, 1933, the United States was in the throes of the Great Depression, and 100 days was about as long as people could wait for relief. The stock market had plunged dramatically, 13 million workers—or nearly 25 percent of the labor force—were out of a job, farmers were losing their land, and banks were collapsing. Things had to change, and fast.

FDR had campaigned on turning things around with the somewhat vague promise of “a new deal for the American people.” Once in the Oval Office, his “New Deal” revealed itself as a top-down effort to use the muscle of the federal government to try and stave off further economic ruin. He pushed 15 major bills through Congress in his first 100 days in office, starting with the Emergency Banking Act, which was rushed through Congress so quickly there weren’t any finished copies available for representatives to read. Welfare bills sent millions of dollars to the states to keep families in their homes and school-aged children fed. A public works program the president himself dreamt up hired hundreds of thousands of workers to repair and revitalize the national parks. The stock market was regulated for the first time ever on the federal level, the sale of low-alcohol beer and wine was legalized again, and Roosevelt still found time to speak directly to the American people and assure them of his commitment to his promises. His first “Fireside Chat” occurred just eight days after his inauguration.

These days, it takes our modern Congresses weeks and months to push through bills, but FDR’s legislative branch became known for its breakneck pace—so much so that the humorist Will Rogers joked at the time, “Congress doesn’t pass legislation anymore, they just wave at the bills as they go by.”

On June 16—105 days post-inauguration but 100 days into Congress’s first session of his first term—Roosevelt signed the Banking Act of 1933, more commonly known as the Glass-Steagall Act, which separated commercial and investment banking, stopped the banks from over-speculating, and created the FDIC to insure customers’ deposits. He’d wrapped up his frenetic 100 days of legislative activity with a law whose main component would stay on the books for the next 60 years.

The Importance of a Strong Start

In the 90-some years since FDR’s landmark first 100 days, no president has been nearly as prolific as Roosevelt was in those early months, but each has still been judged against his record, and presidents can see their legacies begin to take shape in these early days. Lyndon B. Johnson made the bold decision to champion the stalled Civil Rights Act just days after John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush both began fighting for the big tax cuts they’d get passed later in their terms. Barack Obama pushed a massive stimulus bill through Congress within a month. Joe Biden issued 42 executive orders, several of which were aimed at undoing the work of his predecessor.

The first 100 days also began to set the tone for the rest of the administration, and perhaps even the rest of the president’s party as well. One line from Reagan’s inaugural address—“government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem”—is still a rallying cry for modern-day conservatives (though it’s worth noting that Reagan’s full message was addressing the state of the nation and economy he inherited when he said that, not government as a concept or a broader critique of “big government,” as it is often cited today). In 2009, Obama pushed through his stimulus bill without a single Republican vote in the House, and the GOP spent the next eight years complaining that the majority party jammed legislation down their throats without bipartisan consensus.

This 100-day period does offer some advantages to newly minted presidents, though: The electoral mandate is fresh, approval ratings are typically in the green, and the aura of new leadership is powerful, so Congressional enemies usually hold their punches for a bit while they size up the new president and the tone and direction he appears to be taking.

Either way, the First 100 Days metric is a high bar for a new job: Would you want your first three months in a high-profile new position measured against the guy who saved not only America’s confidence but also beer in just his first 100 days?

Read More About Presidents:

A version of this story originally ran in 2017; it has been updated for 2025.