Humans aren’t the only ones who can spot when their friends are about to make a mistake. A new study of chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans has found that our great ape cousins can recognize and attempt to correct false beliefs in others—an ability once thought to belong to humans alone. The findings were published in the journal PLOS One.

It’s called Theory of Mind (ToM): the idea that an individual is aware that others have thoughts and feelings different from their own. Because it requires such complex cognitive processing, scientists have long presumed that we’re the only animals that can do it. However, a series of recent studies has called that presumption into question. In 2015, Japanese primatologists created custom horror movies for apes, then observed the apes watching them to see if they could follow the plot. Then in 2016, they made new movies, specially designed to test the apes’ response to watching other apes (actually people in ape costumes) make mistakes.

The movies showed the fake apes being tricked, then having to make a decision based on faulty information. And sure enough, the audience apes’ eyes lingered on the wrong option onscreen, even though they knew where the right option was. They could predict that the actors were about to get it wrong.

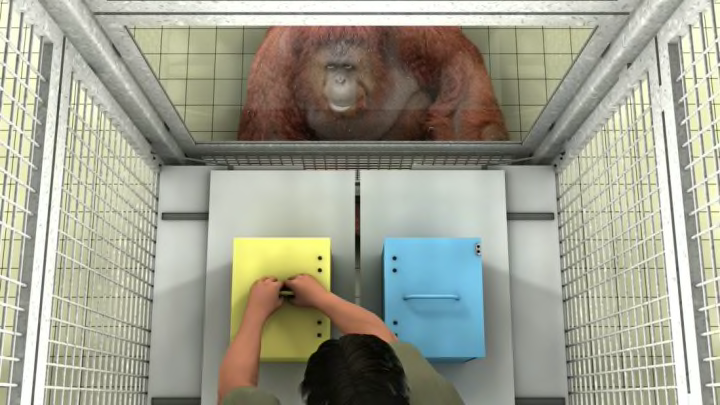

The latest experiment takes these discoveries one step farther, by giving apes a chance to help the hapless actor make the right decision. Researchers taught 34 apes to make a simple, rational decision by placing a noisemaker inside one of two locked boxes while the apes were watching. The ape participants were then asked to select the box with the object inside. Next, they set up a little drama. One experimenter would place the object in the box and lock it, then briefly leave the room. While they were gone, another person would come in, remove the object from the first box, place it inside the second box, then exit before the first person returned.

At this point, the ape knew something the experimenter theoretically did not: where the noisemaker was really hidden. When the experimenter came back, they began pretending to try to open the wrong box. More than 75 percent of the time, the apes would reach for, and help them unlock, the right box instead.

In other versions of the drama, where the experimenter watched the sneak switch the object’s location, the apes didn’t seem to care which box the experimenter eventually opened. They knew the experimenter had this handled. The authors say the findings are another strike against the idea that ToM is a human-only phenomenon.

Developmental psychologist Uta Frith was unaffiliated with the research, but told The Guardian that she found it encouraging. “That is very nice because in evolution there is nothing that comes out of the blue from nowhere.”