Charles Guiteau was seething.

Two decades before he became infamous for assassinating President James Garfield, Guiteau was living in the Oneida Community in upstate New York—and it was his turn for a mutual criticism. As he sat there in the center of a circle of his fellow members, they took turns detailing his faults: He was egotistical, they said, and conceited.

He had heard it all many times before, but Guiteau didn’t say a word—he wasn’t allowed to. Instead, he endured in furious silence.

It was not what he had signed up for. When he had joined the community in 1860, he had expected to take on multiple sexual partners and fully engage in the community’s practice of “complex marriage.” But there was no free love for Guiteau. The women wouldn’t touch him. To make matters worse, members of the community had given him a cruel nickname: “Charles Gitout.” He had to perform manual labor he felt was beneath him—and listen to people insult him.

He had been sent to the Oneida Community by God. He couldn’t believe they weren’t grateful.

- A Complex Community

- Cult or Utopia?

- “Charles Gitout”

- Life at Oneida After Guiteau

- “I Am Going to the Lordy”

A Complex Community

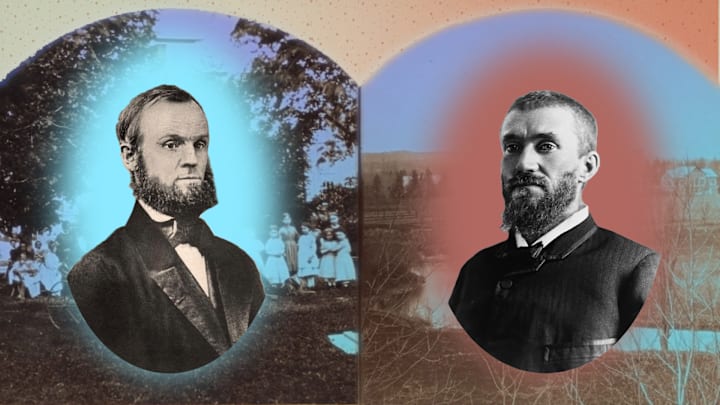

For many people, the word Oneida is synonymous with silverware, which was one of the community’s, and then the company’s, main money-makers for 125 years. But long before it became a manufacturing enterprise, Oneida was a religious utopia founded by a theology school student named John Humphrey Noyes.

Born September 3, 1811, in Brattleboro, Vermont, Noyes was the fourth of nine children, a boy with bright red hair and freckles. His father, John, was a one-term Congressman, and his mother, Polly, was the aunt of future president Rutherford B. Hayes. Despite his mother’s efforts, young Noyes didn’t show much inclination toward religion—in fact, he viewed it cynically—until he experienced an awakening at a revival meeting in 1831, which was followed by a bad cold. These events inspired him to abandon his legal studies and enroll in theology school, first at Andover Theological Seminary in November 1831, and then (after finding his fellow students lacking religious conviction) at Yale Theological Seminary in 1832.

Noyes quickly became involved in the Free Church of New Haven and started gravitating toward Perfectionism, a doctrine with roots dating to the 13th century which posited that, as Ellen Wayland-Smith writes in Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table, “the sinner could not only reform himself by making the right moral choices but also be made ‘perfect’—free from sin—simply by accepting God’s grace.”

Perfectionism resonated with Noyes, and after studying the New Testament, he broke with the traditional church on one very important point: He concluded that the Second Coming of Christ, which would herald an era of glory on Earth, was not something due to happen in the future, as most Christians believed, but instead had already occurred in 70 CE. “Since those early days, all had been in readiness for the eventual perfection of this early life. However, after the first generation of Christians (or the primitive church) had died, their successors had strayed from the true path,” writes Maren Lockwood Carden, author of Oneida: Utopian Community to Modern Corporation. “Since [CE] 70, therefore, earthly perfection had been possible but had never been achieved.”

In February 1834, Noyes delivered a sermon at the Free Church about a bible verse that read “he that committeth sin is of the devil,” and explained that there were no exceptions. Noyes knew there would be pushback—in fact, he was counting on it.

That night, Noyes felt that his heart was cleansed.

The next day, a fellow student challenged him on his sermon. “Don’t you commit sin?” he asked. Noyes responded with an answer that he later said “would plunge me into the depths of contempt”:

“No.”

Noyes later recalled, “When I had convinced [the student] that I actually professed to be free from sin, he went away to tell the news. Within a few hours the word passed through the college and city: ‘Noyes says he is perfect’; and on the heels of this went the report: ‘Noyes is crazy.’ Thus my confession was made and I began to suffer the consequences”—starting with being kicked out of the seminary and having his minister’s license revoked.

But Noyes was far from chastened. Instead, he leaned into his new ideology, preaching in New York and Vermont, starting his own newspaper called The Perfectionist, refining his ideas—and signing up converts, including some members of his own family.

In 1838, he got married, and by the mid-1840s, he and his followers were living in a commune in Putney, Vermont, sharing, in the words of Richard T. Schaefer and William W. Zellner in their book Extraordinary Groups, “their work, their food, their living quarters, and their resources.” Work was evenly distributed among the community’s members; If something needed to be done, everyone was expected to pitch in. Even children would come to be raised communally.

Noyes also began issuing teachings, some more mundane than others. He declared that his community members would partake in mutual criticism, in which they would be criticized one by one in order to improve their character. He provided guidelines for the practice:

- “Criticism should carry no savor of condemnation”

- “Sometimes a person carefully mixes so much praise and extenuation with his censure as not seriously to disturb self-complacency. This is ineffectual”

- “The feeling is natural that it would be hypocrisy to criticise an evil in others unless we are free from it ourselves. This is wrong.”

Other tenets, however, were more bizarre.

According to Wayland-Smith, Noyes took real science of the time—specifically about batteries—and used it to inform his religious vision of sex: He posited that God and Jesus Christ had a battery, and their healing power and life force were passed most potently through “spiritual interchange”—a.k.a. sexual intercourse. Freeing people from the lawful bonds of marriage would allow “the union of male and female [to] fold into the original God-Jesus battery, intensifying its effect,” Wayland-Smith writes, until, when God’s kingdom came to Earth, “each individual life would be enfolded within every other, and the whole of human life enfolded into God and Christ,” ultimately leading to complete triumph over death.

In May 1846, the group began to take its first steps into free love. Initially, the practice was restricted to a few people closest to Noyes, but in 1847, he started to expand the notion of Complex Marriage, in which “all the women of the community were wives of all the men and all men of the community were husbands of all the women,” according to Britannica. The kingdom of God had begun in their commune, he said.

Complex Marriage forbade any two people “to become exclusively attached to each other,” as the community’s 1867 handbook put it: “The Communities insist that the heart should be kept free to love all the true and worthy, and should never be contracted with exclusiveness or idolatry, or purely selfish love in any form.”

Nor should any person have to endure the attentions of a person if they weren’t interested; in fact, it was best for any man who wanted to have a relationship with a woman to make his interest known through a third party, so she could refuse without awkwardness.

Complex Marriage was accompanied by other doctrines. Members would practice what Noyes dubbed Male Continence, or sex without ejaculation, to avoid unwanted pregnancies, as well as Ascending Fellowship, in which older members of the community introduced younger members to sex. Post-pubescent teens were paired with multiple partners in their fifties and sixties.

“It is regarded as better for the young of both sexes to associate in love with persons older than themselves,” the handbook explained, “and, if possible, with those who are spiritual and have been some time in the school of self-control, and who are thus able to make love safe and edifying.” In this scenario, older men who had mastered Male Continence would not be likely to get younger women pregnant, while younger men less skilled in Male Continence would be paired with older women past childbearing age.

The principles were key to the success of the community—and, according to the handbook, fulfilling them presented “little difficulty”: “As fast as the members become enlightened, they govern themselves by these very principles. The great aim is to teach every one self-control. This leads to the greatest happiness in love, and the greatest good to all.”

Oneida’s Odd Practices

The Name | What It Was |

|---|---|

Complex Marriage | A system of sexual freedom in which every member of the Community was “married” to every other member and could sleep with whomever they chose (the key word being chose—no member was forced to sleep with someone if they weren’t interested). |

Mutual Criticism | A gathering of members in which they outlined a particular person’s faults. |

Male Continence | Sex without ejaculation to curb unwanted pregnancies. |

Ascending Fellowship | A practice in which older members of the Community—who had either mastered Male Continence or who were past their child-bearing years—introduced younger members to sex. |

Stirpiculture | A pre-eugenics experiment in which Noyes signed off on whom in the community was allowed to reproduce with whom; the word is derived from the Latin root stirps, meaning “stock, stem.” |

Cult or Utopia?

The word cult had a much different connotation in the 19th century. As Amanda Montell writes in Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism, “cult merely served as a sort of churchly classification, alongside religion and sect. The word denoted something new or unorthodox, but not necessarily nefarious.” (The Manson family murders, and other factors, gave cult its dangerously negative connotation in the 1960s.) In Noyes’s time, there was no shortage of cult-like groups to join; it’s thought that as many as 100,000 people joined utopian communities between 1800 and 1850, and by one estimate, 80 communes sprang up in the 1840s alone.

The Shakers were founded in England in the 1740s, and in 1774, a group of them settled in America. They lived communally, and, unlike Oneida, practiced celibacy, adding children to their ranks through methods like adoption and indentured servitude. (The children were free to leave after they turned 21 if they wished.)

The New Harmony Community was founded in Indiana in 1825 “to pursue the study of the sciences and natural philosophy without the encumbrances of modern, capitalist life,” according to History.com. Bronson Alcott, the father of future author Louisa May, founded a vegan commune called Fruitlands in 1843; it lasted just seven months. Nathaniel Hawthorne spent a few miserable months at Brook Farm—a utopian commune dedicated to scholarly pursuits founded near Boston in 1841 and disbanded in 1847—and used it as inspiration for his novel The Blithedale Romance.

But the proliferation of unusual utopias and new religious movements did not mean that society accepted polyamorism. Noyes and his followers couldn’t hide their free love practices for long (unlike the Mormons, who began practicing polygamy in 1843 and managed to keep a lid on that fact for nearly a decade). When word got out, it drew great attention and condemnation—especially from Putney residents, who grew so incensed that Noyes was arrested and charged with adultery in late 1847.

Rather than face a trial, Noyes abandoned Vermont and moved his followers to New York, where they settled on a tract of land near Oneida Creek and established the Oneida Community. Its goal was to build heaven on Earth—but what Noyes ended up building was one of the longest-lasting, most successful utopias in history.

“Charles Gitout”

By the time Charles Guiteau became part of the Oneida Community in 1860, Noyes and his followers were firmly entrenched in the area. The community, which had grown to more than 200 members, was pulling in plenty of funds by making animal traps, which they began producing in the 1850s. Later, they added the manufacture of silk thread to their economic mix. Plans were even in place to build a 93,000-square-foot Mansion House where all could live communally; it would be completed in 1878.

Guiteau was exposed to Oneida through his father, the odd supporter who did not live in the commune itself; his second wife, Guiteau’s stepmother, simply refused to go. But the elder Guiteau desperately wanted his son to live there. And so, after a failed attempt at a college education at the University of Michigan, Guiteau the younger moved to Oneida, handing over all of the small inheritance he had acquired from a relative over to the community.

It was not smooth sailing. Though Guiteau practically worshipped Noyes, his delusions of grandeur—he even called himself “God’s minute man”—meant he chafed at the community’s requirements for humility, hated that he was forced to do what he perceived to be demeaning chores, and was “practically a Shaker” because he could not get women to sleep with him. That he was forced to sit through numerous mutual criticisms did nothing to curb his behavior, brutal as they were. An outside observer invited to watch a mutual criticism of a person he called “Charles” (almost certainly not Guiteau) wrote that each person in the circle spoke one by one of his faults, and “as the accusations multiplied, his face grew paler, and drops of perspiration began to stand on his forehead.”

When Guiteau asked to leave the community in April 1865 to spread Oneida’s teachings through a newspaper he felt called to create, there likely wasn’t much of a protest. Oneida let him go.

Guiteau packed up and moved to New Jersey to start The Daily Theocrat. For more than three months, he struggled to raise money to get the paper going. His efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, and he begged to come back to Oneida, which was allowed, despite all of his many issues with life in the community. But things did not improve, and a year later, he would be gone for good, this time “sneaking out at night so as to avoid another criticism,” writes Candice Millard in Destiny of the Republic. He asked for the money he’d given to the community, which was eventually returned.

Guiteau next went to Chicago, moved in with his sister, and worked at his brother-in-law’s law firm. After a few months there, he relocated to New York and tried to get a job as an editor at the influential minister Henry Ward Beecher’s newspaper, The Independent, but was only able to secure a job selling subscriptions.

It was a bitter disappointment—life on the outside of Oneida was not working out the way Guiteau had planned. Gradually, his awe of Noyes turned to anger. In late 1867, he sued what he would later call “that stinking Oneida community,” claiming he was owed $9000 from the work he had performed here—the equivalent of around $200,000 today.

Noyes was not at all intimidated. He responded by saying Guiteau was “moody, self-conceited, unmanageable” and “a great part of the time was not reckoned in the ranks of reliable labor.” Noyes also claimed that Guiteau “stole money at various times and in considerable sums from his employers; that he frequented brothels; that he had the venereal disease; and that he ruined his health by self-abuse,” i.e., masturbation.

To Guiteau’s father, Luther, Noyes wrote, “I regard him as insane,” adding, “I prayed for him last night as sincerely as I ever prayed for my own son, that is now in a Lunatic Asylum.” Guiteau’s lawyer eventually dropped the case.

Guiteau, furious, became determined to destroy Oneida.

He threatened Noyes with blackmail: “If you want to spend 10 or 20 years in Sing Sing and have your communities ‘Wiped Out,’ ” he wrote, “don’t pay [my claim].” When Noyes didn’t respond, Guiteau wrote, “If you find yourself arrested within a week, it will be your own fault.” He put out a circular saying that the community was “constantly violating the most sacred laws of God and man; and whereas for the sake of ruined and oppressed women, and for the good of society at large, said Community ought to be ‘cleaned out.’”

But as with many things in Guiteau’s life, none of it came to fruition. He eventually gave up his crusade when Oneida’s lawyers threatened to take him to court, saying they’d use his letters as evidence of extortion.

And so Guiteau moved back to Illinois, where he managed to pass the bar (though he was not more successful as a lawyer than he was at anything else). He got married, moved to New York, and then slept with a sex worker to give his wife grounds for a divorce.

Next came a job as a bill collector, but that ended badly: In 1874, the New York Herald reported that Guiteau had collected $175 on a $350 bill and kept all of it. Guiteau had allegedly explained to his clients that “all respectable lawyers … retain one-half for collection. I have collected my half, and therefore nothing is due to you.” He sued the Herald for libel but eventually dropped the case.

He next attempted, once again, to get into the newspaper business, with no success. In the mid-1870s, Guiteau’s family tried to have him institutionalized after he seemed to threaten his sister with an axe.

Guiteau escaped and went on the run, traveling and giving religious lectures. Eventually, his focus would shift to politics. He became a member of the Republican Party when James Garfield was running for president—with fateful consequences.

The Life and Times of Charles Guiteau

Life at Oneida After Guiteau

With Guiteau no longer an active thorn in Oneida’s side, Noyes and the community moved on. Beginning in 1869, Noyes began further exerting his control over members: With the help of a committee, he signed off on who could procreate with whom. He called the practice “stirpiculture”—from the Latin root stirps, meaning “stock, stem”—and it resulted in the carefully planned births of 58 children over the course of 10 years. (Today, we’d call this experiment “eugenics.”)

Not even incest was forbidden: As Chris Jennings writes in Paradise Now: The Story of American Utopianism, “Noyes carefully documented how God employed the husbandry technique of ‘close culture’ (the inbreeding of close relations to isolate and amplify a desired trait) in His effort to breed ‘the perfect work’—namely, Christ and His apostles.” Noyes had a child with his niece Helen and tried to have a child with his other niece, Tirzah Miller. His brother George (Miller’s uncle) succeeded in doing so.

Eventually, however, things began to unravel.

When Noyes tried to hand off leadership of Oneida to his son, Theodore, in the mid-1870s, the community balked. In 1877—the same year that the community’s Wallingford, Connecticut, outpost began making silver spoons—Noyes made his stance clear, saying that God had determined his leadership and that fact allowed him to choose whom he wanted to next lead the community. That person, he decreed, was Theodore. But Theodore, who lacked faith, struggled in the role, and he resigned in 1878, just around seven months after taking the helm. Noyes was once again the leader of the community, which had reached its peak of 306 members.

But there was more motivating his act than a desire to save the Republican Party—he had a book to sell. As Guiteau wrote in June 1881, “Two points will be accomplished” by assassinating Garfield: “It will save the Republic, and create a demand for my book, The Truth”—a self-published non-seller cribbed from one of Noyes's own books. Guiteau insisted that “This book was not written for money. It was written to save souls. In order to attract public attention the book needs the notice the President’s removal will give it.”

Noyes was becoming increasingly paranoid. He began to fear that he would be arrested—and that his community was turning on him. He fled Oneida on June 22, 1879, under the cover of darkness—just like Guiteau had years before—and settled in Canada. (He died there in 1886.)

After Noyes escaped, Oneida splintered into ideological factions, particularly over Complex Marriage. Some were in favor of keeping things just as they were, with Noyes continuing to decree (albeit from afar) who could sleep with whom; others wanted the ability to choose their sexual partners. Perhaps most surprisingly, a contingent that included Noyes proposed swinging back to more traditional unions or, preferably, celibacy. Mormon polygamy had been outlawed, Noyes reminded them; Oneida could be the next to come under attack.

When the Community took a vote on the proposals in August 1879, Noyes emerged victorious, and this, truly, was the beginning of the end. As researcher Kevin Coffee wrote in “The Oneida Community and the Utility of Liberal Capitalism,” abandoning Complex Marriage did “fundamental damage” because “for most members, [it] was not simply polyamorous sex; it fostered gender equality and defined communal property relationships. … The reinstitution of patrilineal marriage meant competition among men for brides, and among women for husbands. It also meant that female parents assumed principal caregiver responsibility for children, including the children of partners to whom they were not married.”

The community had also started relying on third-party labor in the 1860s, transforming it from a religious group with communist principles to something more capitalist and corporate. In 1881, some 30 years after its founding, Oneida officially disbanded as a utopian community and continued as a joint-stock company after signing a lease to build a factory to manufacture spoons (and other items) on the Niagara Gorge.

Sixty-six years later, the community’s descendants—now officers of Oneida Community Limited—would take the community’s archive, including diaries and other documentation of its free love practices, and send that evidence of their scandalous past up in flames at the local dump.

“I Am Going to the Lordy”

Guiteau, of course, would eventually get the infamy he so badly craved.

As he had believed that God sent him to Oneida to further Noyes’s radical vision, he was convinced that a speech he had given had been instrumental to James Garfield’s victory in the presidential election of 1880. But this was far from reality: Guiteau himself said he only delivered part of the speech because “I didn’t exactly like the crowd. It was a very hot, sultry night, and I didn’t fancy speaking, with the torch-lights and the gas-lights and all that. They put me on the stand as the first speaker, and I spoke a few minutes. There were plenty other speakers there, so I retired.”

To make matters worse, Guiteau had written the speech believing that Ulysses S. Grant would be the nominee; he simply shoehorned in a section about Garfield, rendering the address nonsensical.

His delusions of grandeur intensified. Guiteau believed he was due a patronage position in the Garfield administration; it did not materialize, despite the fact that he basically haunted both the White House and the State Department making his wishes clear. Guiteau so badly harassed Garfield’s secretary of state, James Blaine, that Blaine supposedly erupted, “Never speak to me again on the Paris Consulship as long as you live.”

When Garfield got into a dispute with a senator about a patronage position in New York, Guiteau’s view of the president changed dramatically. He came to believe that Garfield was going to destroy the Republican Party—and that the only way to deal with it was to eliminate Garfield.

After praying about it, Guiteau decided that God had signed off on this plan. His evidence, one newspaper explained, was that there had been “several attempts upon his [Guiteau’s] life, and [he] considered his escape proofs of special interposition of Providence on his behalf.”

But there was more motivating his act than a desire to save the Republican Party—he had a book to sell. As Guiteau wrote in June 1881, “Two points will be accomplished” by assassinating Garfield: “It will save the Republic, and create a demand for my book, The Truth”—a self-published non-seller cribbed from one of Noyes's own books. Guiteau insisted that “This book was not written for money. It was written to save souls. In order to attract public attention the book needs the notice the President’s removal will give it.”

Guiteau stalked the president for weeks. He spent at least a week editing The Truth because “I knew it would probably have a large sale on account of the notoriety that the act of removing the President would give me, and I wished the book to go out to the public in proper shape.” Finally, on July 2, 1881, Guiteau shot Garfield twice at the Baltimore and Potomac train station in Washington, D.C.

The president died on September 19, 1881 after months of agony. That same day, Guiteau wrote to the new president, Chester A. Arthur, “My inspiration is a godsend to you and I presume that you appreciate it. … Never think of Garfield’s removal as murder. It was an act of God, resulting from a political necessity for which he was responsible.”

No one else agreed with this assessment. During his trial, Guiteau claimed legal, but not mental, insanity—God, he said, had taken his free will—but his lawyer (and brother-in-law) George Scoville did his best to show that Guiteau was so mentally unstable he couldn’t determine right from wrong. To that end, Scoville brought up the axe incident with Guiteau’s sister and put the assassin himself on the stand to delve into his childhood, his religious writings, and his time at Oneida—and even with his life on the line, the assassin could not resist taking a few digs at his former community.

“I want you to imagine yourselves in hell, ladies and gentlemen … and then you can form some idea of my experience in the Oneida Community,” he said, adding later, “I am very glad to say that the Oneida community is wiped out.”

Guiteau was found guilty and hanged in 1882—but not before he managed to publish a revised edition of The Truth, titled The Truth and the Removal. On the gallows, he read a poem he had written just that morning that he said “indicate[s] my feelings at the moment of leaving this world.” It read, in part:

“I saved my party and my land,

Glory hallelujah!

But they have murdered me for it,

And that is the reason I am going to the Lordy,

Glory hallelujah! Glory hallelujah!

I am going to the Lordy!

I wonder what I will do when I get to the Lordy,

I guess that I will weep no more

When I get to the Lordy!

Glory hallelujah!”

Discover More Stories About History: