When someone is put on trial for a crime, it’s fair to expect that they’ll be alive, but that isn’t actually always the case: There have been a handful of posthumous trials throughout history. And while it may seem a little pointless to try a defendant who’s already dead—seeing as how they can’t defend themselves and there are limited punishment options if they’re found guilty—there are a few reasons that such trials have been conducted. They can be used to seize the deceased’s estate, provide closure for the plaintiff, or serve to exonerate someone who was wrongfully convicted in life.

Still, for obvious reasons, posthumous trials aren’t all that common, so here are 10 instances where dead people faced the courts—and why.

- Gilles van Ledenberg

- Pope Formosus

- Sergei Magnitsky

- Joan of Arc

- Alexander and John Ruthven

- Martin Bormann

- St. Geneviève

- George Gordon

- Farinata degli Uberti

- Henry Plummer

Gilles van Ledenberg

On August 29, 1618, Gilles Van Ledenberg—a leader of the Remonstrants, an exiled religious movement—was arrested for treason. He thought his children would be able to inherit his property if he passed before the trial took place, so he died by suicide in September. But he was wrong. Van Ledenberg was tried and convicted the following May; his estate was confiscated, and his body—now embalmed and mummified—was sentenced to be hanged. His corpse was shoved into a coffin and then the whole thing was suspended from a gibbet and left for 21 days before being buried in a cemetery.

Not fully satisfied with Van Ledenberg’s punishment, a mob of youths then dug up his coffin, desecrated his body, and threw it in a ditch. The court wasn’t too happy with this act of vigilante punishment and issued an injunction to prevent further tampering with the body.

You Might Also Like ...

- 25 “Trials of the Century” and the Media Frenzies That Accompanied Them

- The 10 Most Intriguing True Crime Stories of the Decade

- Murder in the Red Barn: The Crime Solved by a Dream

Add Mental Floss as a preferred news source!

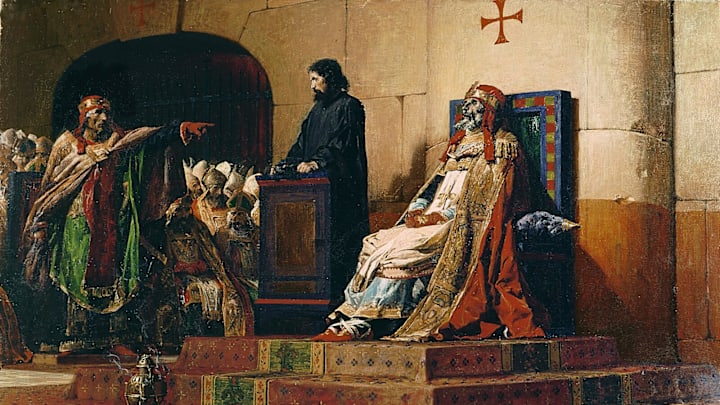

Pope Formosus

Pope Stephen VI was eager to erase the legacy of his predecessor’s predecessor, Pope Formosus (Pope Boniface VI ruled in between them for just 15 days), so in January 897, he accused him of usurpation. The trial—now popularly called “the Cadaver Synod”—was a macabre affair. Formosus had died nine months earlier, but Stephen VI insisted that his body be present in court. Formosus’s rotting corpse was exhumed, dressed up in ecclesiastical robes, and sat on the papal throne. Although Formosus was allocated a deacon to speak on his behalf (because he obviously couldn’t speak for himself), Stephen VI did most of the talking and, of course, won the case.

All of Formosus’s papal ordinations and consecrations were nullified. His body was dressed in rags, the three fingers he used to perform blessings were chopped off, and he was chucked into the Tiber River—a fate that was reserved for the most infamous criminals in Ancient Rome. It was done to prevent his remains from becoming venerated holy relics, but Stephen VI’s plan didn’t quite work out: A fisherman pulled Formosus’s body from the river and returned it to the tomb in St. Peter’s Basilica.

Sergei Magnitsky

In 2008, lawyer Sergei Magnitsky was arrested for reporting tax fraud committed by Russian officials. He died 11 months later in prison, having been beaten by guards and denied medical care for pancreatitis. But that didn’t stop the Russian government from putting him on trial and finding him guilty of tax evasion in 2013.

There was massive international outcry about Magnitsky’s treatment both before and after his death. In 2019, an investigation by the European Court of Human Rights concluded that the Russian government had committed several human rights violations. Along with the denial of medical care and physical abuse, it was also declared that “the length of his detention was unjustified” and “the posthumous trial was inherently unfair.”

Bill Browder, founder of Hermitage Capital Management—the investment firm that Magnitsky was working with when he discovered and exposed the high-level corruption—said that the ECHR’s ruling “completely destroys the lies and propaganda about Sergei Magnitsky.”

Joan of Arc

It’s well-known that Joan of Arc, the teenage military leader who fought for France, was burned at the stake after being charged with heresy. English forces managed to hold onto Rouen for almost 20 years after her execution—which occurred on May 30, 1431—but once they were driven out, her mother and two brothers pushed for her case to be retried. Pope Calixtus III agreed, and the documents from Joan of Arc’s trial were re-examined.

On July 7, 1456, the Inquisitor-General concluded his investigation and gave his final pronouncement: the original trial was nullified because of fraud and improper procedure. All charges were dropped. Not only was Joan of Arc’s name officially cleared, but she was also declared a martyr and in the following years she became a national symbol of France.

Alexander and John Ruthven

On August 5, 1600, a fight broke out when Alexander Ruthven took King James VI of Scotland to Gowrie House as part of what some believe was an attempt to murder the monarch. Who started the conflict and why remains unknown, but James’s royal attendants heard him cry out for help through a turret window and immediately sprang to his aid. Both Alexander and his brother, John Ruthven, the 3rd Earl of Gowrie, were killed in the fight.

The event became known as the Gowrie Conspiracy. The dead men obviously couldn’t tell their side of the story, but James claimed that they tried to assassinate him. The Ruthven brothers’ bodies were preserved so that they could stand trial, and on November 15, 1600, the two were convicted of treason. They were stripped of their honors and estates and even their family name was “extinguish’d and abolish’d for ever,” with members of the Ruthven clan being forced to choose new surnames. Their bodies were also punished; they were hanged, drawn, and quartered and the separate body pieces were then displayed in Edinburgh, Stirling, Dundee, and Perth.

Martin Bormann

Technically, Martin Bormann—a high ranking member of the Nazi party and Adolf Hitler’s private secretary—was tried in absentia at the Nuremberg trials in 1946, rather than posthumously, because it was unknown whether he was dead or whether he had managed to flee Germany.

Bormann’s defense lawyer, Friedrich Bergold, argued that the court couldn’t convict him because he was already dead. But Bergold didn’t win that argument and Bormann was sentenced to death by hanging for his war crimes.

The search for Bormann initially didn’t lead anywhere. But in 1972, his remains were thought to have been found in Berlin. After examining the body’s teeth, it was deemed highly likely that the remains were indeed Bormann—a fact then later confirmed in 1998 after a DNA test. The Nazi official had died on May 2, 1945, likely by biting into a cyanide capsule to die by suicide—meaning that he was tried posthumously after all.

St. Geneviève

For hundreds of years, the body of St. Geneviève—the patron saint of Paris, who died around the year 500—rested peacefully at the Church of the Holy Apostles, which became known as the Church of St. Geneviève after miracles were reported to have occurred at her tomb. That all changed at the end of the 18th century, though, when secularization swept through France with the French Revolution.

In 1791, the Church of St. Geneviève was renamed the Panthéon and became home to the remains of Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, the president of the National Assembly. Geneviève’s shrine and remains were moved to the nearby Saint-Étienne-du-Mont; they eventually ended up in the Hôtel des Monnaies. The revolutionary regime then put her bones on trial and convicted her of “[participation] in the propagation of error.” Her bones were burned and then the ashes were tipped into the Seine. Only a few small relics of Geneviève now remain.

George Gordon

On October 28, 1562, George Gordon, the 4th Earl of Huntly, faced off against the forces of Mary, Queen of Scots at the Battle of Corrichie. The fight was over the Earldom of Moray: Huntly claimed it was rightfully his, but Mary had given it to her illegitimate brother, James Stewart. Huntly lost the battle and was imprisoned in Aberdeen Tolbooth, where he collapsed and died that night, being described as “gross, corpulent and of short breath.”

Mary wasn’t going to let death get in the way of convicting him, though. Huntly’s body was disemboweled and pickled before it was transported to Edinburgh. In May 1563—seven months after Huntly’s death—the trial took place, with the Earl’s body put on display in an open and vertically-standing coffin. His pickled remains were found guilty of treason; his corpse was then left unburied at Holyrood Palace. It took three years before the body was released and Huntly was finally interred in his family’s tomb at Elgin Cathedral.

Farinata degli Uberti

Farinata degli Uberti was a 13th-century Florentine nobleman who led the Ghibelline faction—a political group that supported the power of the Holy Roman Emperor, as opposed to the Pope. Uberti died in 1264, but 19 years later both his body and the body of his wife, Adaleta, were exhumed and put on trial by the Catholic Inquisition. They were both found guilty of heresy (because Uberti didn’t believe in an afterlife) and the property their sons had inherited was confiscated.

Uberti showed up as a character in Dante’s Inferno in the 14th century. He resides in the sixth circle of Hell, alongside other Epicurean heretics who don’t believe the soul lives on after death.

Henry Plummer

On January 10, 1864, Henry Plummer—the sheriff of Bannack, Idaho Territory—was accused of being the leader of an outlaw gang that had been committing murders in the area. A vigilante group decided to take matters into their own hands by hanging Plummer from a scaffold that he himself had built to hang a horse thief.

Plummer was definitely to blame for a few murders over the years. For instance, he shot John Vedder in self-defense while protecting John’s wife, Lucy, from domestic abuse. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison for that murder, but was released after a petition signed by more than 100 officials attested that he had “an excellent character.” Whether Plummer really did become the leader of an outlaw gang or whether that very gang murdered Plummer is uncertain to this day.

On May 7, 1993—129 years after he was executed—Plummer was given a mock trial. Montana’s Twin Bridges Public School District staged the event as part of a history class, with students playing the roles of people who would have been involved had Plummer been given a fair trial. The trial took place in a real courtroom with a real judge; 12 registered voters served as the jury. In the end, the jury were split on the verdict, leading the judge to declare a mistrial—meaning that Plummer would have been freed.