The idea of binding a book in human skin might seem like something found only in fiction—there’s the Necronomicon in the Evil Dead franchise and the sentient spell book in Hocus Pocus—but there are a number of real examples from history. The macabre practice is known as anthropodermic bibliopegy, and there are a variety of (highly questionable) motivations behind it, from the punishment of criminals to doctors wanting symbolically meaningful covers for their medical tomes.

Until fairly recently, it was hard to verify whether a binding was made from human skin or from the skin of another animal because the leathers look virtually identical. But modern technology—specifically peptide mass fingerprinting—means that books can now be conclusively tested. The Anthropodermic Book Project has so far tested 32 books allegedly bound in human skin, with 18 found to be genuine.

Libraries have taken different approaches to the skin-bound books in their collections. Some restrict borrowing access or remove the skin entirely—as Harvard’s Houghton Library did in 2024 with a copy of Arsène Houssaye’s Des destinées de l’âme (The destinies of the soul), “due to the ethically fraught nature of the book’s origins and subsequent history.” On the other hand, some libraries display their examples. Megan Rosenbloom—a member of the Anthropodermic Book Project team and author of Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin—believes that “evidence of atrocities are still historically valuable” and that the books should be preserved for study.

If you’re interested in learning more about these darkly fascinating books, here are 11 confirmed examples to peruse.

- De integritatis et corruptionis virginum notis

- Speculations on the Mode and Appearances of Impregnation in the Human Female

- Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral

- De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem

- “Le Scarabée d’Or”

- Le Traicté de peyne

- An Authentic and Faithful History of the Mysterious Murder of Maria Marten

- An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy

- Narrative of the Life of James Allen

- The Dance of Death

- Mademoiselle Giraud, my wife

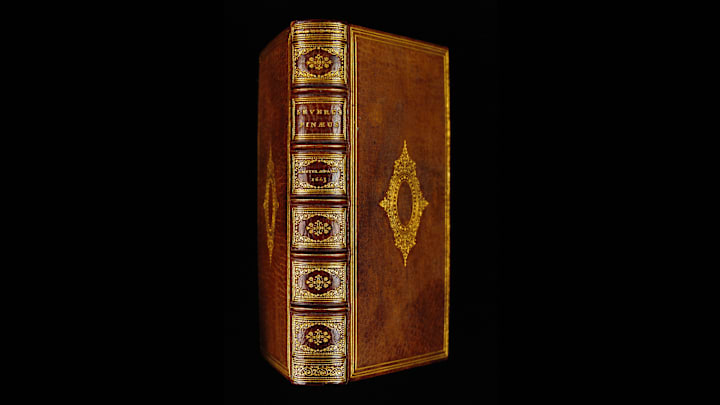

De integritatis et corruptionis virginum notis

When Ludovic Bouland was training as a medical student at a psychiatric hospital in Metz, France, during the 1860s, he removed some of the skin of a recently deceased female patient (whose name is unknown). Years later, the doctor then used the skin to bind two books in his collection. One was a 1663 edition of Séverin Pineau’s treatise on virginity, De integritatis et corruptionis virginum notis (On the marks of integrity and corruption of virgins). “This curious little book on virginity, which seemed to me to deserve a binding in keeping with its subject matter, is bound with a piece of woman’s skin that I tanned myself with some sumac,” Bouland wrote on one of the book’s blank pages.

The other book that he bound in skin is Houssaye’s Des destinées de l’âme (1879)—the book that Harvard eventually deskinned. Bouland again included a note which explained his reasoning behind the binding: “A book about the human soul deserved to have a human covering.”

Speculations on the Mode and Appearances of Impregnation in the Human Female

Another doctor with a penchant for anthropodermic bibliopegy was John Stockton Hough. In January 1869, Hough performed an autopsy on the body of Mary Lynch, who had been admitted to Philadelphia General Hospital the previous summer for tuberculosis and then caught trichinosis (a disease caused by a parasitic roundworm). He removed a piece of skin from Lynch’s thigh and tanned it in a chamber pot.

In 1887, almost 20 years later, he bound the spines and edges of three medical books with the skin: A 1650 edition of a remedy book by French court midwife Louise Bourgeois, a human anatomy textbook by Louis Barles from 1680, and Robert Couper’s Speculations on the Mode and Appearances of Impregnation in the Human Female (1789).

Hough also had at least two other human skin books in his collection. His copy of Charles Drelincourt’s De conceptione adversaria (1686) was bound using, according to a note Hough wrote in the book, the “skin from around the wrist of a man who died in the [Philadelphia] Hospital 1869.” (The man may have been a patient named Thomas McCloskey.) It isn’t known whose remains Hough used to bind Catalog des sciences médicales (1865), but, unlike his other skin books, he didn’t store the skin for long before using it.

You Might Also Like ...

- 8 (Supposedly) Cursed Books

- Quiz: Can You Guess the Stephen King Book Based on a Synonym?

- 6 Reportedly Haunted Libraries

Add Mental Floss as a preferred news source!

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773), penned by Phillis Wheatley, is the first known poetry book to be published by a Black American woman. In order to publish the book, Wheatley had to first silence critics who didn’t believe the poems she had previously published could have been written by an enslaved Black woman. She was forced to prove herself in front of a panel of influential white Bostonians—after she did so successfully the book was finally published. There are two known copies of her poetry bound in human skin, but it’s not known whose skin it is, who did the binding, or why they did it.

De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem

Of all of the books to be clad in human skin, a book on the subject of human dissection may seem to be the most fitting. First published in 1543, Andreas Vesalius’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (On the Fabric of the Human Body in Seven Books) was a landmark text in understanding human anatomy. Along with correcting previous anatomical errors, Vesalius’s books included more than 200 woodcuts to illustrate the body. At least one volume of this historic scientific work is bound in human skin—it’s now shelved at Brown University’s John Hay Library.

“Le Scarabée d’Or”

If any works by Edgar Allan Poe were going to be bound in skin, then you might think that his spooky poems and stories—like “The Raven,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” or “The Fall of the House of Usher”— would be the likeliest candidates. But the only known skin-clad Poe story is actually “The Gold-Bug,” a not-at-all-spooky treasure hunt tale first published in 1843 that may not be well-known today, but was his biggest success in his own lifetime.

It's an 1892 French edition of the story, titled “Le Scarabée d’Or,” that’s bound in skin. “Dear John—What a tribute to the morbid death-loving Poe to find the ‘Gold Bug’ in human skin,” reads the inscription by author Charles Erskine Scott Wood. It isn’t certain who “John” is, but there’s a chance this copy was given to John Steinbeck, who was friends with Wood.

Le Traicté de peyne

New York’s Grolier Club houses the only known example of an erotic text bound in human skin: Le Traicté de peyne (The Tract of pain). This French BDSM poem was penned during the first half of the 16th century by someone identified only as “Tant brun” (although this may be the name of the copyist, rather than the original author) and it’s dedicated to the Duke and Duchess of Lorraine.

“It’s a little pocket book, as you might imagine a sexy kind of book would be,” Rosenbloom said in an interview with The Morbid Anatomy Online Journal, “that’s something that you would hide, right?” The book is an 1868 edition, but its provenance beyond that—who covered it in skin and why—remains unknown.

There are also rumors of erotic novels written by the Marquis de Sade—who gave his name to the word sadism—being bound in a woman’s breast skin; actual evidence of these books is yet to be found, but they may exist in a private collection.

An Authentic and Faithful History of the Mysterious Murder of Maria Marten

On August 11, 1828, William Corder was publicly executed after being convicted of murdering his lover, Maria Marten, a year earlier. Known as the Red Barn Murder, the case had become famous throughout England and between 7000 and 10,000 people are said to have gathered to watch Corder hang. His body was then dissected, and the surgeon, George Creed, tanned his skin and used it to cover two books about the murder case. One is entirely covered in skin, while the other only features skin on the spine and corners.

The fully-clad book has been on display at Moyse’s Hall Museum, in Suffolk, England, since 1933, but the partially-clad one was lost within the building and was only rediscovered in 2024. “I know you’re not supposed to burn books, but quite honestly these are such sickening artifacts,” Terry Deary, the Horrible Histories creator who once played Corder in a stage show, told the BBC. “These are two books I’d like to burn.” Dan Clarke, heritage officer at West Suffolk Council, admits that the books are “uncomfortable history,” but believes that “if we are to learn from history we must first face it with honesty and openness.”

An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy

During the latter half of the 19th century, many American medical students had a copy of Joseph Leidy’s An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy (1861). The author’s personal copy of the popular textbook was a little different from the others, though. “The leather with which this book is bound is human skin, from a soldier who died during the great Southern rebellion” (a.k.a. the Civil War), the inscription in the book reads. The identity of the soldier is unknown. The book now lives at Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum and was described by the descendent who donated it as “a most cherished possession” of the doctor’s.

Narrative of the Life of James Allen

In most instances of anthropodermic bibliopegy, the person whose skin is used wasn’t asked for consent, but that wasn’t the case with the Narrative of the Life of James Allen, which was bound in Allen’s skin at his own request. Allen was a notorious highwayman from Massachusetts and had his crime-filled memoir transcribed by a prison warden shortly before he died in 1837. He asked that his skin be used to cover two copies of the book—one of which was to be given to his doctor and the other to John Fenno Jr., a man who impressed Allen by fighting against the highwayman’s attempt to rob him.

The cover of the skin-bound memoir is stamped with the Latin words Hic liber Waltonis cute compactus est, which translates to “This book is bound in Walton’s skin” (Walton was one of Allen’s aliases). It’s thought that the copy that wound up in the Boston Athenaeum might have been donated by Fenno Jr.’s daughter.

The Dance of Death

The allegorical motif known as the Dance of Death, or Danse Macabre, dates back to the medieval period and represents both the inevitable and universal nature of death. In 1526, Hans Holbein the Younger created a series of woodcuts themed around this motif—in the form of skeletons interacting with the living—and they were published in a book in 1538. The Dance of Death proved to be massively popular and spawned many editions, some of which were bound in human skin.

Six copies of the book are said to be skin-clad, but only two—both at Brown University’s John Hay Library—have been verified as authentic. The 1816 edition features a note explaining that the front cover is smooth and the back rough because the binder was “obliged to split the leather in two” because of the size of the book, while the 1898 edition is decorated with a skull, bones, and arrows.

Mademoiselle Giraud, my wife

When Adolphe Belot published Mademoiselle Giraud, ma femme in 1870, it proved to be both popular and controversial, thanks to the titular character refusing to consummate her marriage with her husband because she’s a lesbian. For some reason, someone thought that this scandalous French tale should be bound in human skin: An 1891 English translation of the book is covered half in skin and half in marbled boards.