King Arthur, Sir Gawain, and plenty of other chivalric characters are still well known in today’s culture. But one hero is a huge mystery: Wade. A new translation of an old manuscript reconsiders the nature of his adventures.

Wade, From Old Norse Myths to Chaucer

According to Old Norse legend, Wade is a giant born to a fearsome warrior king, Vilkinus, and a mermaid. His son Wayland becomes a great smith after Wade apprentices him to the most renowned dwarf smiths. Wade also features heavily in Kudrun, a Middle High German epic in which he helps a Danish king win the hand of an Irish princess (by subterfuge, military force, and basically kidnapping).

We know Wade was a familiar figure to medieval English folks, too, because he’s mentioned in multiple works from that time and place—including two by Geoffrey Chaucer. In Troilus and Criseyde, Chaucer wrote that Pandarus “tolde tale of Wade” to Criseyde, his niece, after a supper contrived to unite her with the besotted Troilus. Some scholars have interpreted this move as a way to get Criseyde in a romantic headspace.

Chaucer invoked Wade again in The Canterbury Tales’ “Merchant’s Tale,” wherein the elderly knight January says he’d rather marry a woman under 20 than someone 30 years or older in part because old widows “konne so muchel craft on Wades boot”—in modern English, “they know so much trickery on Wade’s boat.” Editor Thomas Speght added a note about this reference in the appendix of a 1598 collection of Chaucer’s works: “Concerning Wade and his bote called Guingelot, as also his strange exploits in the same, because the matter is long and fabulous, I passe it over.” It’s up for debate whether Chaucer intended Wade’s boat as a reference to tall tales and deceit in general or something more specific—particularly something involving a magical ship, a common motif in chivalric romance.

In a 1966 paper, Chaucerian scholar Karl Wentersdorf connected both of Chaucer’s references to Wade’s adventure in Kudrun. Pandarus, like Wade, was trying to facilitate a relationship. As for the trickery on Wade’s boat, Wade united the royals by concealing warriors on a specially crafted ship and, after whisking the princess onto the ship, having them battle her father’s troops. Would Chaucer’s 14th-century audiences have known this older German tale? Some scholars are dubious.

Moreover, it’s not totally in line with how Wade is deployed in other medieval English literature. He usually gets name-dropped alongside esteemed chivalric knights and heroes, with the implication that Wade himself was among the best of them. But what he did to earn such an illustrious reputation is unclear—because no English account of his own story has ever been found.

Deciphering The Song of Wade

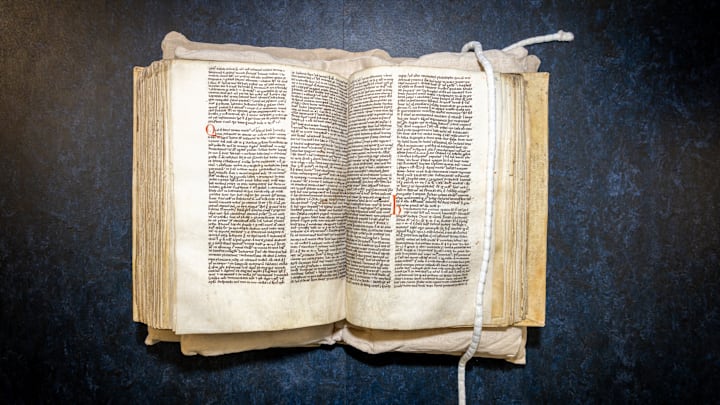

All we have from this elusive Song of Wade, as historians call it, is a few lines of Middle English quoted in a Latin sermon from the early 13th century. Medievalist M.R. James discovered it in a manuscript at Peterhouse, a University of Cambridge college, in 1896. He and his fellow scholar Israel Gollancz transcribed the quote as follows:

“Summe sende ylues

and summe sende nadderes:

summe sende nikeres

the [bi den water] wunien:

Nister man nenne

bute ildebrand onne.”

They translated this into modern English as “Some are elves and some are adders; some are sprites that dwell by waters: there is no man, but Hildebrand only.”

Between the lack of standardization in spelling and the wealth of variation in scribes’ handwriting (not to mention typos), translating Middle English is a very inexact science. Scholars have long toyed with that initial translation and pondered what the verses mean in the context of the sermon—and what they can tell us about Wade. (It’s generally assumed that the legendary hero Hildebrand must be Wade’s father in this telling.)

In a new paper published in The Review of English Studies, Seb Falk and James Wade offer their take on the verses. They translate the Latin introductory phrase as “Thus they can say, with Wade,” and the Middle English verses like so:

“Some are wolves and some are adders; some are sea-snakes that dwell by the water. There is no man at all but Hildebrand.”

The biggest divergence from previous translations is the switch from elves to wolves. Falk and Wade argue that the y of ylues in the original manuscript should have been transcribed as a w based on the way similar-looking letters in the passage were translated; moreover, elves in Middle English wasn’t typically spelled with a y. There’s even more compelling evidence in the Latin sentence directly after the quote from Wade’s story, which begins with “Similiter, hodie aliqui sunt lupi.” In English, that’s “Similarly, today some are wolves.”

Falk and Wade have also translated nikeres as “sea-snakes” instead of “sprites.” In Old and Middle English, the term was used for various sea monsters and supernatural beings associated with the sea, from kelpies and sirens to mermaids. It also sometimes referred to hippos.

The paper argues that the whole translation moves The Song of Wade away from the realm of old Germanic mythological beasts and characterizes it as a pretty down-to-earth chivalric romance—a human story of heroism and righteousness in the face of cunning and dastardly men. That said, the authors acknowledge that these spheres aren’t mutually exclusive. Plenty of chivalric romances feature supernatural beings and other fantastical elements; and there’s crossover in the characters of folkloric myths and chivalric romances.

In short, even if The Song of Wade involved wolves (or just cruel, wily men) instead of elves, it’s still possible that the titular hero sailed on a magical ship. But the details of his adventures—and what exactly Chaucer meant by mentioning them—will remain hidden until someone finds a better source.

Learn More About Medieval History: